There are several similarities between Eric Zemmour and the Dutch politician Pim Fortuyn, and one distinct difference. The Dutchman was homosexual and an ardent campaigner for gay rights, whereas the Frenchman, who has three children, recently reaffirmed his opposition to gay marriage.

But on Islam and immigration they had much in common. Fortuyn, for example, campaigned for a reduction in the overall annual number of immigrants to Holland from 40,000 to 10,000, with not one Muslim among that figure. Zemmour wants an end to all immigration and believes that Islam ‘is not compatible with France’.

Fortuyn paid with his life for his views. He was assassinated on May 6, 2002, nine days before the Dutch parliamentary elections. It was a killing that shook Holland, its first political murder since the 17th Century, although some on the left didn’t particularly mourn the death of the flamboyant Fortuyn.

Like Zemmour his political rise was as rapid as it was unexpected. A sociology professor at the University of Rotterdam, the 54-year-old Fortuyn came to nationwide prominence through a newspaper column, warning of the dangers he believed Holland would face in the years to come from Islamic extremism. In 2001 he declared his ambition to stand for Prime Minister and in February 2002, just three months before the election, he founded his own party, Pim Fortuyn List. A month later his party astounded the Dutch political establishment by winning 17 of the 45 seats in Rotterdam’s municipal elections.

Zemmour is the new danger to the European extreme left

That is when the threats and intimidation began. He was hit with a pie by a left-wing activist a few days after that election success, and in the weeks that followed Fortuyn was heckled and jostled wherever he went. Some of the world’s media piled in – Ireland’s Sunday Independent described him as a ‘right-wing extremist’ – although others offered a more nuanced appraisal. Dismissing as unfair comparisons with Mussolini, the Economist said ‘Fortuyn’s speciality is saying aloud, in plain Dutch what many of his fellow citizens feel’.

But this straight-talking terrified the centre-left coalition government, which, in the words of the Observer in an article on April 14 2002, ‘scrambled to denigrate Fortuyn.’ The Dutch Labour PM, Wim Kok, labelled Fortuyn a ‘danger to the country’, and one of his MPs drew comparisons with 1930s Germany.

But, explained the Observer, these character assassinations were failing, because: ‘Highly articulate, telegenic, oozing charisma, he has wiped the floor with establishment politicians in TV debates and his views seem to strike a chord with many in the most densely populated country in Europe.’

In the end, a young left-wing militant environmentalist Volkert van der Graaf decided to eliminate the possibility of Fortuyn becoming Prime Minister by pumping five bullets into his back and head as he left a radio studio. At his trial van der Graaf justified his action by describing Fortuyn as a ‘danger’ (echoing the words of Wim Kok) who had made Dutch Muslims ‘scapegoats’.

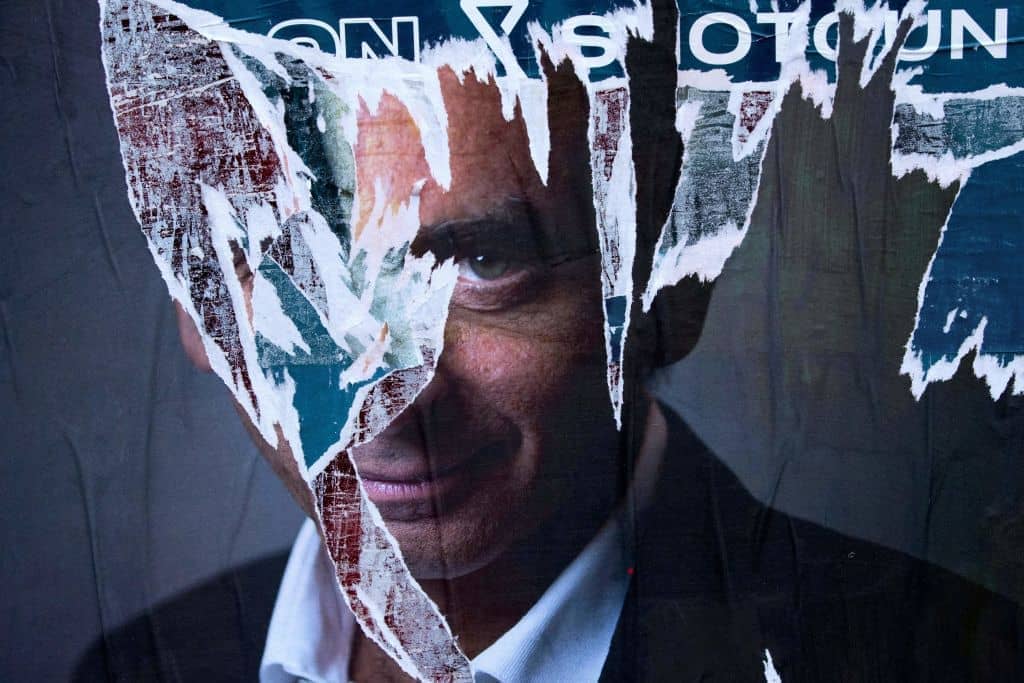

Zemmour is the new danger to the European extreme left. On the eve of his visit to Nantes last weekend, posters appeared across the city on which a gun sight was super-imposed on Zemmour’s forehead. Above was written in English: WANTED.

Accompanying posters urged people to demonstrate against Zemmour’s presence in Nantes in the name of anti-fascism. Hundreds did and there were violent scenes in the city centre on Saturday afternoon as police fought to prevent Antifa activists gaining access to the venue hosting Zemmour.

This was the latest, and largest, threat made against Zemmour, but there have been others, establishing a sinister pattern not too dissimilar to the one experienced by Fortuyn in 2002.

In September a man confronted Zemmour in the street and swore ‘on the Quran’ that he would harm him, while last month a left-wing comedian said he wished he could travel back in time so that he could organise an Eric Zemmour rally at the Bataclan theatre on November 13, 2015 (the night Islamists murdered 90 people at a rock concert).

Zemmour is a provocative man with, as I wrote last week, some disagreeable ideas, but it is imperative that in the months ahead the French state does its utmost to ensure he is allowed to express his opinions openly and without fear of injury or worse. At the same time his political rivals must choose their words with care. Challenge, debate and debunk but don’t demonise. The Socialist candidate, Anne Hidalgo, has been particularly vituperative of late. Not only is she refusing to engage with Zemmour, she has deployed irresponsible invective, describing him as ‘negationist’ and a ‘racist’ who disgusts her. It’s a particularly cowardly politician who insults an opponent but at the same time refuses to meet them in a debate.

Hidalgo would do well to remember the actions of the Dutch political class 20 years ago who not only failed Fortuyn but failed democracy.

Comments