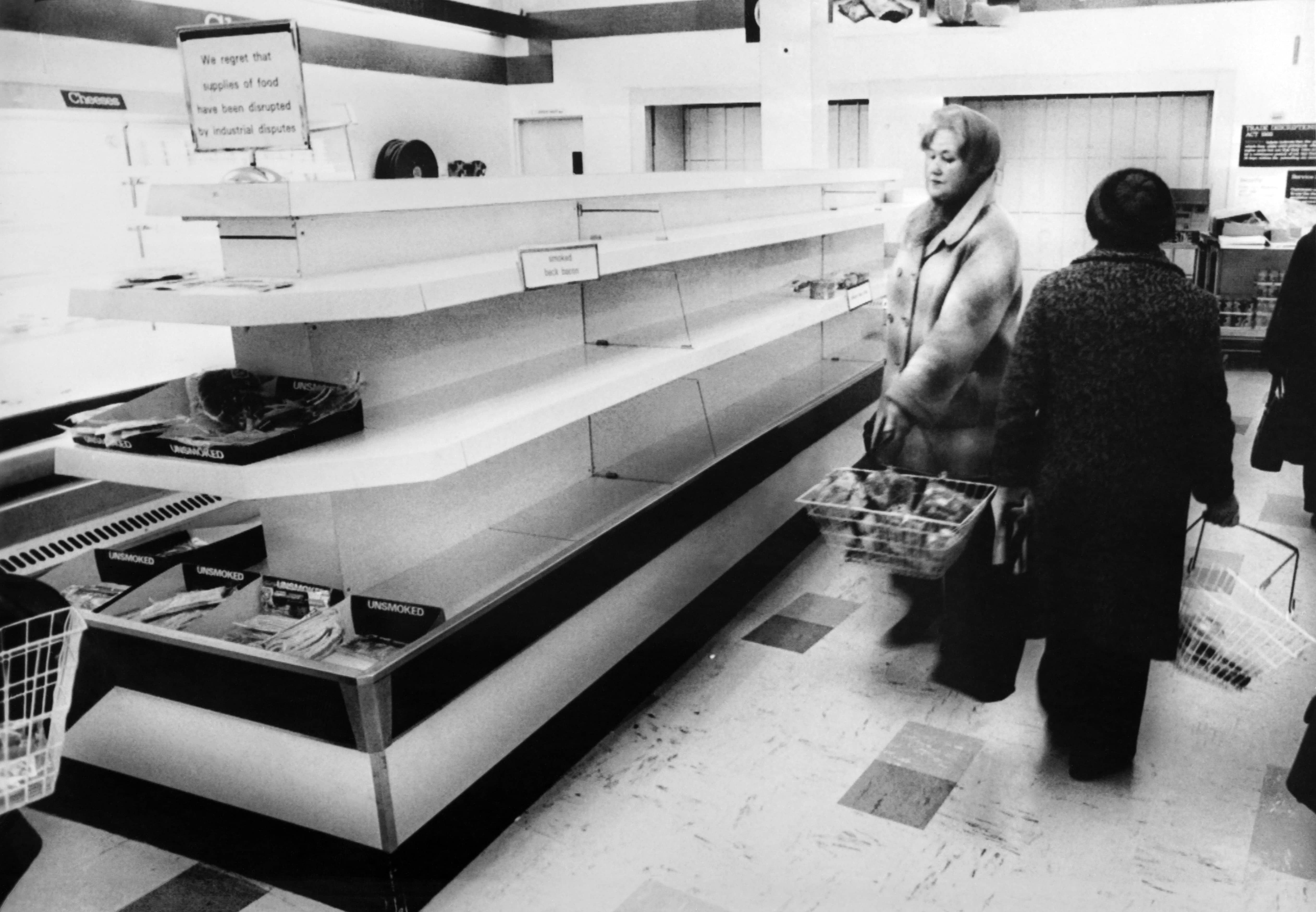

There are eerie parallels with 1970s at the moment, I say in the Times today. The inflation of that decade was principally caused by the abandonment of the gold standard in 1971 and the oil shock of 1973-4, which saw the price of a barrel of oil go from $3 a barrel to $12. Today, we have seen huge amounts of quantitative easing from central banks to keep the economy going through Covid – and unlike the post-financial crash QE, which was largely used to repair banks’ balance sheets, it has gone into the real economy. On top of that, we have now seen the gas price rise fourfold. There are other supply issues too; just look at how the shortage of lorry drivers is affecting petrol deliveries.

Unlike the post-financial crash QE, which was largely used to repair banks’ balance sheets, it has gone into the real economy

High energy prices are a big driver of inflation and energy companies are already pushing Ofgem to lift the household price cap by 20 per cent from April. Economists think this alone would increase inflation by 0.3 per cent. The danger is that this marks a shift to structurally higher energy prices — so inflation won’t be temporary.

The Bank of England is now warning that warning that inflation could reach 4 per cent by the end of the year and stay there until next summer. If it persists much longer than that, the Bank will have little choice but to raise interest rates. This would come as an unpleasant surprise to mortgage holders who, after more than a decade with the Bank base rate below 1 per cent, have either forgotten or never known the angst of rates above that. The average variable mortgage, with 75 per cent loan-to-value, is 1.8 per cent. It could double very easily, triggering a repayment crisis and hurting household finances far more than next April’s National Insurance rise.

Combine this with the coming £20 cut in Universal Credit, and it is easy to see how the cost of living could become the dominant political issue in Britain in the coming months.

Comments