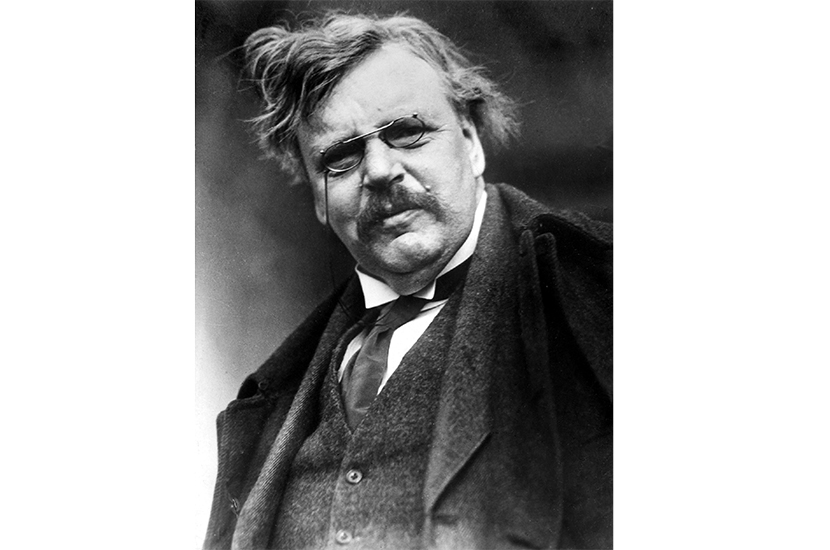

The Sins of G.K. Chesterton demands our attention because, as Richard Ingrams notes in his introduction, the literature on this author is (with a few notable exceptions) horribly flawed — littered with misconstruction, omissions of fact and interpretive errors designed to present him as ‘an innocent, uncomplicated man, blessed with almost permanent happiness and having no experience of suffering — hence an ideal candidate for canonisation’. That flourish, appearing in Ingrams’s third to last paragraph, was a bombshell to me, though I understand there exists a sizeable constituency pressing for Chesterton’s beatification, rebuffed in 2019 when Bishop Peter Doyle of Northampton condemned his anti-Semitism.

Ingrams’s predecessors are guilty of trying either to ignore or to cleanse what-ever might blemish the appearance of saintly virtue. Ingrams instead provides a detailed explanation of how misplaced loyalty to his younger brother Cecil led Chesterton to adopt the anti-Semitic views of Hilaire Belloc, to whom Jews were un-British parasites, consisting largely of bankers and businessmen determined to take over the world.

Chesterton’s fidelity to ‘the Bellocian manifesto’ led him in turn to support fascism. He met Mussolini in Rome, and when Italy invaded Abyssinia in 1935 wrote that Britain had no right to ‘issue a moral rebuke’, condemning those who disagreed for deferring to the same ‘Jewish conspiracy’ that vindicated Dreyfus. In the year Oswald Mosley married Diana Guinness at the home of Joseph Goebbels, Chesterton could write: ‘Fascism is worth looking at, whereas parliamentarianism is not worth looking at.’

travel guidelines.’

Such pronouncements are nothing if not preposterous, yet are mere splinters compared with the industrial quantities of pine planking that comprise Chesterton’s disquisitions on the ‘Jewish problem’ which, he said, could only be solved by establishing a Jewish homeland in Palestine, to which British Jews should be shipped. Jews, he wrote, ‘should be represented by Jews, should live in a society of Jews’. It must take a loathing of considerable magnitude to propose that throngs of one’s fellow citizens, born and brought up in Britain, be forcibly removed to the Middle East. Short of which, he added — in a proposed article for the Daily Telegraph, which happily they declined to publish — Jews in Britain should be ordered to dress ‘like an Arab’ so ‘we should know where we are, and know where he is, which is in a foreign land’. Like wearing the yellow Star of David on one’s clothing, n’est-ce-pas?

All in all, Ingrams’s is an account of someone who wilfully followed the idiotic, bigoted views of fascists and anti-Semites, irrevocably tarnishing Chesterton’s posthumous reputation, something most biographers have preferred not to accept (had they done so, there would have been no occasion for this book). It reminds me of how Byronists love to imagine their idol a womaniser rather than the self-confessed ‘lover’ of 15-year-old boys.

Except that Chesterton’s depredations are worse in both degree and kind. From the vantage point of 2021, we view anti-Semitism through the filter of the Holocaust, because that is the obscenity with which such opinions culminated. And there can be no excusing it. You don’t apologise for fascism; our duty is to judge and condemn it.

Faut-il brûler Chesterton? Ingrams says that the Father Brown stories possess classic status and uses the term ‘genius’ to describe their author. But views as deplorable as Chesterton’s must and should affect our judgment of him as a man and, by extension, his writings, just as they have irrevocably stained our views of Pound and Eliot. These things matter. An artist’s inability to perceive the venality of fascism is a serious flaw in his or her moral and political judgments, which in turn poses a huge and unignorable reproach to the art. The ‘much-loved Father Brown stories’ are hailed for their humanity, but how is that quality to be squared with their author’s opinion of Jews?

Ingrams provides a thorough account of the evidence supporting the case that Chesterton’s views were assumed out of loyalty to his brother — but if granted, that would be inconsistent with the man’s supposed genius. In the 1930s, W.H. Auden, George Orwell, Sylvia Townsend Warner and John Cornford, to name a few, recognised the evils of fascism and were prepared to fight it; Cornford died in the attempt. That Chesterton remained blind to what was transparently clear to them makes him a lesser writer and diminishes him as a thinker. It confounds his status as genius and exposes the absurdity of imagining him as saint.

Excuses abound in the world of Chesterton studies; would that they counted. It’s a given that as adults we reach our own conclusions about the world and take responsibility for them. Chesterton never recanted; he used his position as a journalist to promulgate fascism, and should be held accountable for that.

Ingrams’s book has much to be said for it, not least the attempt to put straight a disturbingly partial record. But he falls short of his own rigorous standards when he asks us to imagine Chesterton as a tragic hero. There’s precious little here to justify that, and in hankering after such a verdict, Ingrams opens himself to the charge of lacking courage equal to the evidence. This is ironic, given that his theme is pusillanimity — that of biographers, acolytes, scholars, groupies, and fascists such as G.K. Chesterton.