When conservatives renege on election-time promises not to raise taxes, they tend not to be forgiven in a hurry. ‘Read my lips: no new taxes’, promised George H.W. Bush, words that Bill Clinton did not let Americans forget. John Major also promised not to raise taxes, then hiked National Insurance, blaming unforeseen circumstances. Tony Blair never let up, arguing that the Tories had forfeited the right to be believed on financial promises. In the 2005 campaign, the Tories announced they would not make any tax promises because they would not be believed. Once you renege on a promise, credibility takes a decade — perhaps more — to repair. I look at this (and the risks of big-state conservatism) in my Daily Telegraph column and we discuss it in today’s Coffee House Shots.

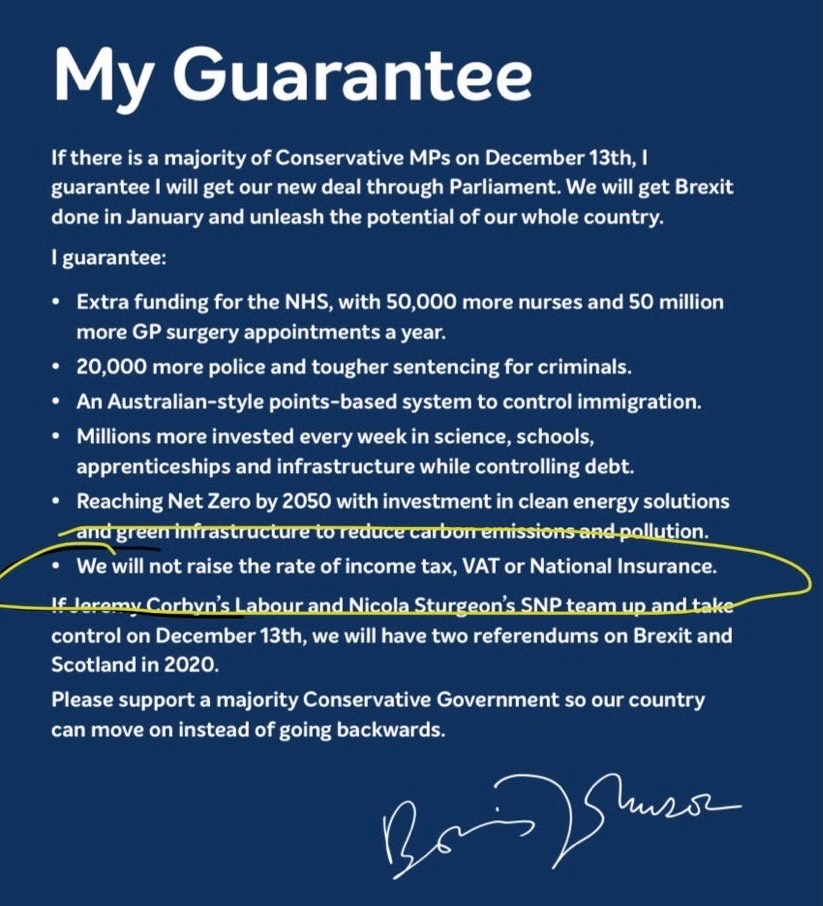

A cast-iron guarantee was offered to voters by Boris Johnson when he stood for election. The manifesto is his contract: a very small list of hard promises upon which the credibility of Conservative MPs is based.

We promise not to raise the rates of income tax, National Insurance or VAT. This is a tax guarantee that will protect the incomes of hard-working families across the next parliament. We not only want to freeze taxes, but to cut them too.

Given recent events, I’d support a tax rise if it would genuinely clear the Covid-induced NHS backlog or repair the appalling damage to education. Such a tax rise could be temporary: say for three years until the work is largely done.

But we’re not talking about post-pandemic social repair. The tax rise planned for next week would be on care homes financing — a move dodged by governments for 20 years because of the huge costs and problematic implications of asking the average voter to subsidise the old and wealthy. This is a lurch away from one-nation conservatism, and instead aligns the Tories more closely to the interests of the propertied classes.

The Tory manifesto, for the record, was vague about how social care funding would be reformed. On the steps of No 10 Johnson later gave a verbal pledge to ‘fix the crisis in social care once and for all’. It was a rash promise as he had no plan, which is why, in a panic, he reheated the 2011 Dilnot proposal that David Cameron rejected as too expensive. We can now expect a cap on what people are expected to contribute of about £50,000 — perhaps £80,000, if the Treasury gets its way. But there would be no reform of the sector, just a transfer of money.

It’s a bit of a stretch to add a ‘five-figure inheritance’ to this list of indignities that the government needs to protect people from

To me, this is the precise opposite of what government is supposed to be about. The guys with the power and money ought to be helping those with less of it: this is the rationale for the welfare state. (And, to me, the rationale of politics.) Theresa May’s idea — provide better care home support to those who could not otherwise afford it and leave the rich to look after themselves — made sense. Right now, anyone with assets under £23,250 can qualify for help. By all means, let’s look at this threshold and the level of support. But May’s principle was sound. If you are rich, you don’t really need financial help from the average taxpayer.

Johnson’s idea — provide a subsidy to save wealthy families from having to sell too much of their assets — turns the notion of social protection on its head. The recent (absurd) asset boom means that one in four UK pensioners lives in a millionaire household, a dazzling statistic. Why should their assets be protected by the average UK taxpayer on a salary of £30,000 a year?

The asset boom has distorted the economy and exacerbated wealth inequality, leaving families with unexpected windfalls. Houses bought for £350,000 some 20 years ago are worth £1.2 million now (to pick a random example from Boris Johnson’s constituency). Such constituencies are full of people whose family finances have been transformed by the unforeseen asset boom. This created a huge divide in British society: between families with property and families without it.

Rather than ‘level up,’ the Tories now propose to tax people on the poorer side of this divide to protect those on the richer side. And break a manifesto pledge to do so.

It’s quite a moment. When Johnson says he will protect ‘your parents or grandparents from the fear of having to sell your home to pay for the costs of care’, he is talking about inheritance. Not fixing care. The Dilnot proposals would not add an extra care home bed, nor address the flaws in the care home system that saw a third of Covid dead perish in such homes.

It’s also wrong to think that all pensioners are okay with this. After James Forsyth and I discussed on this morning’s Coffee House Shots podcast, a listener got in touch. His email sums it up:

I am 75, in a house worth over £2 million, have a final salary pension on top of the state pension and I am appalled at the idea that working-age people should be taxed to help fund my care should it ever be needed. As it happens, I would expect to fund (at a much higher rate than provided by the state) my own care out of both income and assets, but it is deeply immoral as well as bad economics.

Boris Johnson is not the first prime minister to say that he’d protect people from the supposed calamity of selling their house to pay for their care. David Cameron did so too and commissioned Andrew Dilnot — then concluded that it was ‘not the right moment to be implementing expensive new commitments such as this’. Boris Johnson thinks that it is the right moment. That’s all that’s changed. This is the hill on which Tory tax credibility is about to die. Nothing to do with the pandemic.

I’ve never seen the problem with anyone selling their house, or any other asset, to pay for the care they need. Not everyone has big savings, so the state ought to look after the vulnerable. The idea of welfare for the middle-class (and the stonkingly rich) is not just expensive but deeply inequitable. Especially when you consider how much of this is really about the size of the inheritance: those admitted to care homes are, alas, unlikely to return to their home.

To talk about ‘having to sell your home’ as being some kind of horror will certainly jar with younger voters who can’t afford a house and have given up hope of ever being able to do so. Is this really a priority for a cash-strapped government? Asset protection? The welfare state was set up to combat the ‘five giant evils’ of squalor, ignorance, want, idleness and disease. It’s a bit of a stretch to add a ‘five-figure inheritance’ to this list of indignities that the government needs to protect people from.

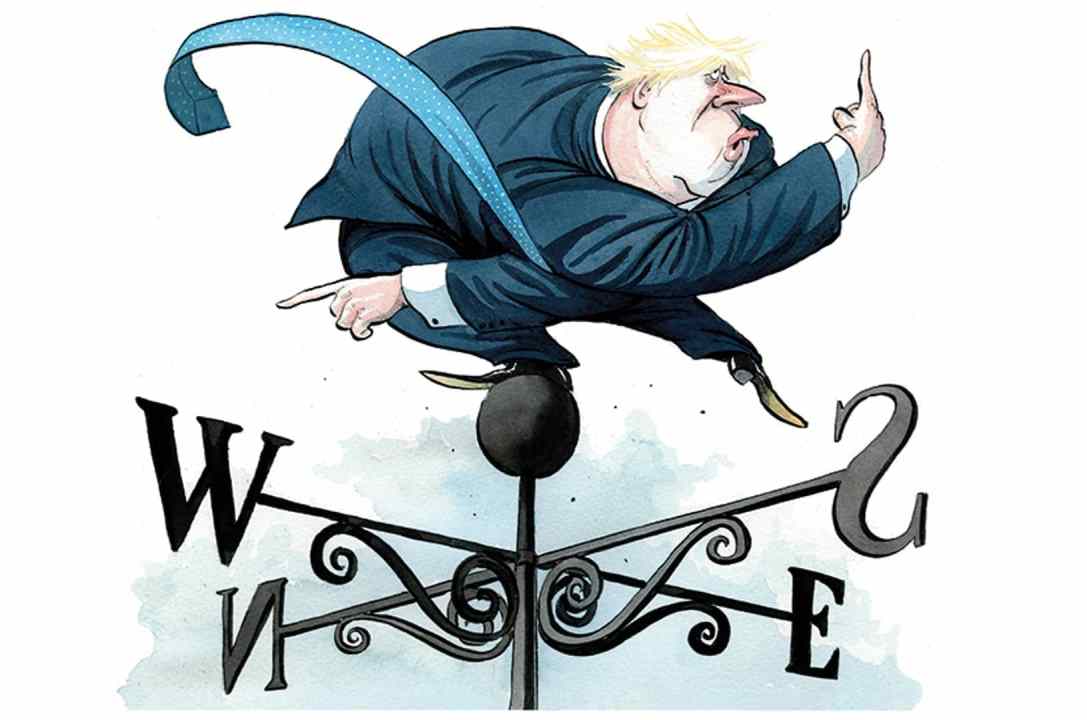

Boris Johnson really didn’t want to make a tax pledge in 2019 but his campaign chief Isaac Levido persuaded him it was vital if he wanted to win. In a tight race with the left, it’s the most potent card the right to play: ‘you may not like us much, but at least we can guarantee that we won’t up you tax bill. It’s a serious, cast-iron pledge with the PM’s personal signature: trust us’. When conservatives can no longer make this pledge — because they panicked in office — they’re defanged, far easier to beat. As Blair and Clinton found out.

Look at the below: Boris pitched this one of six promises to voters, complete with his signature. Note the absence of anything about care homes.

To break the manifesto pledge to fix the pandemic damage would be — just about — politically excusable. To use the pandemic as cover to break tax pledges in order to finance a massive bung to a Tory-voting demographic would be less defensible. It devalues not only his promise, but any election-time promise made by any Tory.

The Blair tax rise was presaged by the Wanless review and deep thinking about this massive gambit. This time around there has been no consultation with the cabinet, let alone MPs or the country. A shame, because there is all too much to discuss.

Comments