Colin Jones’s hour-by-hour reconstruction of the fall of Maximilien Robespierre, the French revolutionary most associated with the Terror, is inspired by Louis-Sébastien Mercier, who believed that only by getting ‘up close’ to the ‘infinitely small’ details would it be possible to understand the truth about a Revolution that was stranger than fiction.

Mercier (1740-1815) was an early science fiction novelist, a journalist, politician and Parisian. He was not an eyewitness to the fall of Robespierre because he was in prison in 1794, one of 73 moderate members of the governing Convention who had been arrested and held as ‘Robespierre’s hostages’. The Convention was a representative body of 749 deputies, charged with designing a republican constitution for France. But only 200 were required for quoracy, so the Convention could function without the 73 moderates and without the many others who had been sent out ‘on mission’ to impose order on a country riven by foreign and civil war.

On 28 July 1794, 9 Thermidor, Mulberry Day in the revolutionary calendar, Robespierre and his close colleague Saint-Just planned to make speeches at the Convention that would lift the veil on the most recent counter-revolutionary conspiracies, foreign plots and corruption. Saint-Just was known for carrying his head around as though it was the holy sacrament, and Robespierre was nicknamed ‘the Incorruptible’.

Many of the condemned smiled as they mounted the scaffold – in a silent sign of symbolic resistance

They were a sanctimonious and terrifying pair, determined to set the new republic on a path of virtue, and concerned about the ‘impure breed’ of people who might blight the social and economic sunlit uplands they saw ahead. Together they had pushed through legislation known as the 22 Prairial Law, by which it became easier and quicker to identify and execute ‘enemies of the people’. So-called ‘batches’ of the supposedly guilty were going under the guillotine every day. In these circumstances, announcing that yet another plot was about to be unveiled caused every member of the Convention, and many others besides, to fear for their lives.

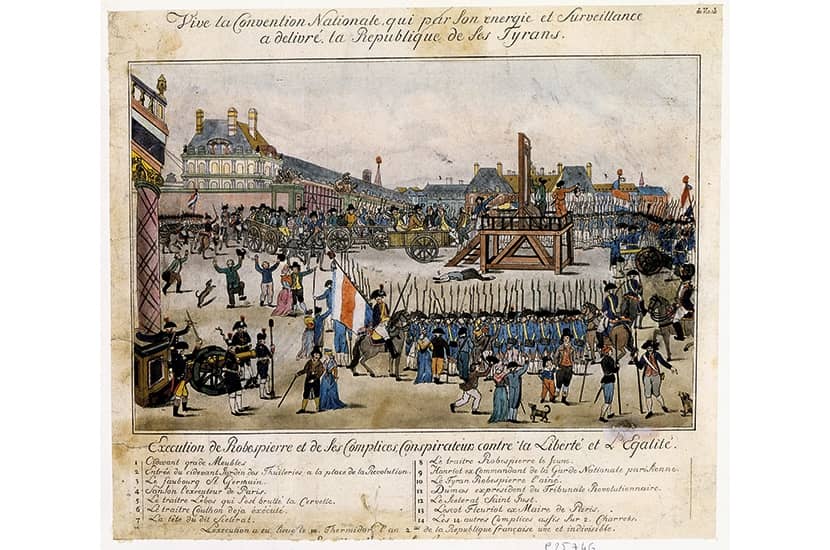

Saint-Just stayed up into the early hours of the morning perfecting his speech, whereas Robespierre slept soundly and reassured the artisan family with whom he lodged in the rue Saint-Honoré that there was nothing to fear as he set off for the Convention after an abstemious breakfast. However, both men were prevented from delivering their speeches; instead arrest warrants were issued for them and their closest associates. There then ensued a further 24 hours of uncertainty, during which Mulberry Day turned into Watering Can Day, and it only gradually became clear that the people of Paris would ultimately support the Convention, not side with Robespierre, Saint-Just and the city’s Commune which had risen, or half-risen, in their defence.

Jones is clear that this is a book as much about Paris as about Robespierre. The hour- by-hour constraint he adopts allows him to broaden the narrative to include a panorama of Parisian life. Many were expecting 9 Thermidor to be a day of protests against the imposition of a wage maximum for Paris, an economic levelling policy that would have led to massive wage decreases for carpenters, blacksmiths and other workers. The police were busy with routine tasks: a locksmith and his wife, for example, were arrested at 3 a.m., while Robespierre was sleeping soundly, for possessing an Old Regime coin with Louis XVI on it, and a bunch of suspicious keys. ‘People have been guillotined for less,’ Jones remarks, deploying the historic present to electrifying effect. Later that morning, the revolutionary tribunal is about its grimly normal business. Forty-four people are sentenced to death, as well as the Princesse de Monaco, left over from the day before when she pretended to be pregnant to extend her life by just one day so she could cut her own hair off and bequeath it to her children.

Jones, whose previous books include The Smile Revolution in 18th-century Paris, notes that the hardened executioner Henri Sanson, descended from a family of executioners under the Old Regime, finds that many of his charges, struggling to master their feelings, smile as they mount the scaffold: ‘On the road to the guillotine, the smile has become a silent weapon of symbolic resistance.’

Assembling a wealth of detail from a vast range of archival resources, Jones sometimes revivifies the intensity of those revolutionary days in a way reminiscent of Hilary Mantel’s A Place of Greater Safety. But ultimately he is a historian, and there are questions that he wants to answer. Was Robespierre mad in the run up to 9 Thermidor? He had been absent from the Convention for six weeks before he announced his forthcoming speech on the need for another purge. He spoke of ‘unburdening his heart’, but in fact he was committing political suicide.

Jones argues this was not madness: it was typical of Robespierre’s abstract reasoning about the will of the people, which he claimed to vocalise without dominating. ‘A man who has never managed much in his life is unlikely to be able to manage an insurrection,’ Jones scathingly remarks. For him, Robespierre emerges a charismatic incompetent with the highest of all possible moral tones. In contrast, Mercier saw Robespierre as a ‘sanguinocrat’, or ruler by bloodshed.

Jones concludes that there was no elaborate plot against Robespierre that led to his downfall, and nor was he seriously conspiring to become a dictator or tyrant: ‘The day was not pre-planned. It just happened.’ It was only afterwards that it came to seem inevitable. In deciding to back the Convention over Robespierre, Saint-Just and the Parisians prepared to fight for them, the majority of the people in the streets chose institutions over personalities or political celebrities. For this reason, Jones argues, Robespierre’s fall was his greatest contribution to democracy, even though in its aftermath much of the democratic promise and progressive social and economic policies that had emerged since 1789 were destroyed. 9 Thermidor was about removing a man, not a government or a regime. Or as Marc Antoine Baudot, another of the members of the Convention, put it: ‘It wasn’t about principles; it was about killing.’

Comments