The Lord of Misrule is surely the jolliest spirit of Christmas past. He is certainly the best named. He used to gambol through cities and courts, churchyards and dining rooms, telling jokes, performing tricks and spreading good cheer. Society shook itself upside down at his coming, so knaves played at being kings, children became miniature tyrants and noblemen misplaced their manners (an exercise in which some, admittedly, needed little assistance).

His origins can be traced back to ancient Rome, where each December masters and slaves swapped places for the festival of Saturnalia and engaged in various acts of tomfoolery while gorging on food and wine. These traditions survived the advent of Christianity and found their own expression in the Church. The medieval ‘Feast of Fools’ witnessed the lowest ranking members of the clergy usurp the positions of the highest. And ‘Boy Bishops’ donned the cloth, delivered sermons to the adults and took in the collection. Everything was topsy turvy.

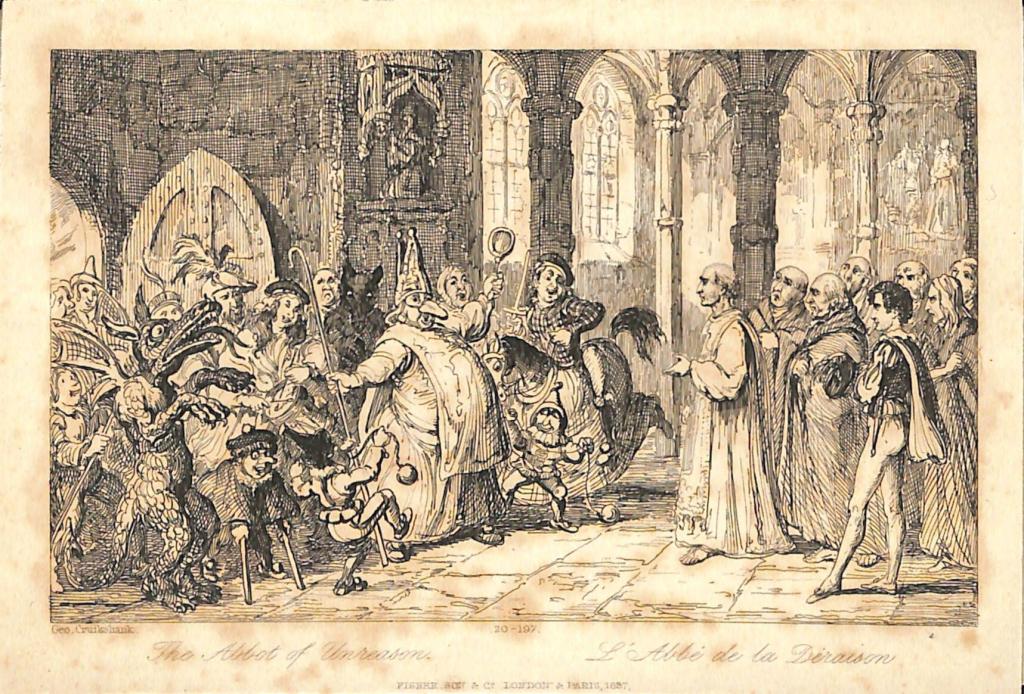

Naturally such scenes found a place in art. The caricaturist George Cruikshank (1792–1878) drew one of the Lord of Misrule’s common associates, the Abbot of Unreason, leading a party of revellers into an abbey:

The collective noun for monks is an ‘abomination’, which is just about the only word you can imagine Cruikshank’s monks spluttering as the obese Abbot of Unreason and his acolytes stream in with their hats, hobby-horses and balls and chain. ‘Lustie guttes’ was the name one disapproving writer attached to the Lord of Misrule’s followers. This lot look positively ravenous.

They were as popular in royal courts as they were in the inns of court. Henry VII employed a Lord of Misrule and Abbot of Unreason almost every Christmas of his married life, and his mother, Lady Margaret Beaufort, was similarly partial to the custom. Edward VI paid one of his father’s favourites a handsome wage to entertain him over Christmas at Greenwich in 1552. The glorified jester then boated down the Thames to eat meat with the Lord Mayor.

They were as popular in royal courts as they were in the inns of court. Henry VII employed a Lord of Misrule and Abbot of Unreason almost every Christmas of his married life

Edward’s beloved Lord of Misrule was the quite famous George Ferrers. A lithograph from the early 19th century shows him in ermine, feathered cap and full swagger. ‘A wise gentleman, and learned’, Ferrers trained as a barrister before entering royal service and enjoyed a number of roles in his life. As Lord of Misrule, he was celebrated for his prowess at entertaining ‘the common sort’, as the chronicler Holinshed put it, as well as the less common sort. In the print, attributed to James Stephanoff, the amiable Ferrers attracts the attention of everyone in town – people lean out of windows and chase after him with flags.

The civil disturbance was not always welcomed. Philip Stubbes, author of an Elizabethan Anatomie of Abuses, snarled at the ‘wanton colour’ of the revellers’ clothes, and the jingling bells and ‘hande-kercheefes’ the accompanying Morris dancers laid across their shoulders, ‘borrowed for the moste parte of their pretie mopsies and loovyng bessies’. How sacrilegious it was to see them marching with stuffed dragons, pipes and drums towards the church!

It was a good thing Stubbes did not live to see Jacob Jordaens’s painting of 1640-5. If there was ever a bawdier Christmas table, I am yet to see it:

Everyone is drunk, even the child, who is as oblivious to the dog salivating over her cup as she is to the figure throwing up just behind her. One lusty gutte has a woman by the cheeks and another has forgotten where his mouth is; his attempt to lower some food into his gullet is positively painful to watch. ‘Nothing is more like a fool than a drunk,’ reads the Latin inscription above the fireplace. To which, presumably, the gathered said a toast.

The painting is entitled ‘The Feast of the Bean King’ (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna). Particularly popular in Europe, the Bean King was much like the Lord of Misrule in spirit, but his status depended upon chance. Only the person served the portion of cake or bread containing a bean was entitled to wear the crown and bear the title. He or she could then choose a royal spouse from the party and lead the celebrations.

There are allusions to Bean Kings in early 14th-century England, Scotland and France, but Northern Europe was more than slightly keen on the bean. David Teniers the Younger (1610–90) put his king in a paper crown while a bell-hatted jester danced beside the table. In ‘The Bean Feast’, the Dutch artist Jan Steen (1626–79) awarded the crown to the youngest child at the table (his poor sibling has to make do with a wicker basket for a hat) and captured the chaos by laying a trail of broken eggshells across the floor:

These paintings belong to the period when the Puritans were striving to stamp out Christmas celebrations in England as indecorous, irreligious and plain offensive. The laws passed in the 1640s, which constituted something close to a ban on the above, sent the remaining Lords of Misrule into hiding. It was ironic that a ballad sung to protest the legislation was entitled ‘The World Turned Upside Down’. While the virtuous denied themselves their mince pies, and the unvirtuous slunk into taverns on the sly, lords and ladies made merry in their own way. It was not quite the same.

Unreasonable abbots and queens of beans would pop up here and there as time went on, but the kingdom of misrule had had its day – or so they thought. Just imagine how at home they’d feel in 2022.

Comments