In one particularly excruciating scene in The Office, manager David Brent tells everyone that they are about to lose their jobs, but ‘the good news is I’ve been promoted’. When challenged, he says, ‘Well I couldn’t come out and say I’ve got some bad news and some irrelevant news.’

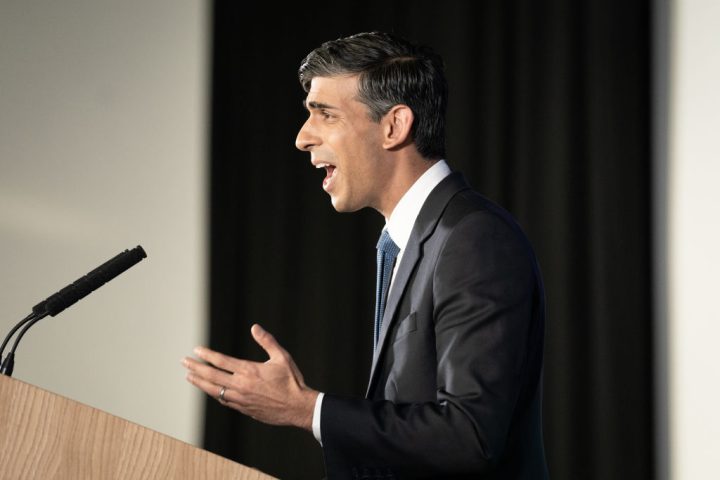

A similar exchange seems to have just happened with Rishi rather than Ricky. The bad news is that the NHS is in crisis, with up to 500 people dying a week due to delays in emergency care and one in three ambulances waiting over an hour to hand over patients. The ‘good’ news though is that Sunak, after almost two months of silence, has announced that he wants all students to study maths up until 18.

The strange and surreal timing aside, Sunak’s policy simply doesn’t add up. The UK is indeed an outlier compared to other OECD countries such as Germany, Japan and America, who all have compulsory maths until 18. There’s also no denying that there are some serious failings in our current maths education (according to one study, around half of UK adults have the numeracy skills of primary school children). Yet whilst Sunak may have grabbed some distracting headlines, he has failed to show his working.

The problem is we simply do not have enough maths teachers. The government has failed to meet its maths teacher recruitment targets every year for the last decade, despite dangling generous bursaries for maths PGCE students of up to £27,000. The Tories have actually cut their recruitment aims by 39 per cent since 2020, whilst nearly half of secondary schools use non-specialists to teach maths because of chronic shortages. Anecdotally, the vast majority of Teach First maths teachers I met during my time on the programme did not study maths as their degree, but were conscripted after having applied for another subject.

The problem is we simply do not have enough maths teachers

The second critical problem is that the policy is wildly out of touch with our current educational reality. Maths is already the most popular A-level by far, with almost 100,000 students each year (when I took my A-levels in 2011 this was English, which sadly now does not even make the top 10). Yet far, far more students fail GCSE maths each year: 230,000 students, around a third of the average school year, retook maths GCSE last summer, with only 20 per cent passing on their second or subsequent attempt.

The fact that so many students continue to fail to get a level 4 at GCSE is a damning indictment of our current system. But despite what the government may think, the last thing society needs is more division.

What is the point of making these students sit through two more frustrating, futile years, especially when there is such a huge gap between our current curriculum and its applications for most people? It would be one thing to request students to undertake some sort of qualification in financial literacy or the basics of economics and business. But why submit students who are far more suited to a vocational education to polynomials and logarithms?

The Tories have already cut funding for apprenticeships and narrowed the choice of qualifications by replacing BTecs with T-levels. This policy feels like yet another constriction of a curriculum that is crying out for more breadth rather than depth.

Last year the Times Education Commission recommended a more wide-ranging British Baccalaureate, with slimmed-down exams at 16 allowing for greater combination and choice at sixth form. This would mean students could mix and match rather than be forced down a simple binary of academic versus vocational or arts versus sciences.

If Sunak wants us to compete internationally, why not go even further? The European model (the International Baccalaureate) currently makes some form of maths, English and one modern language compulsory until 18, allowing scope for students to value creativity and communication as well as crunching numbers.

As an English and History teacher it is disheartening to see arts funding cut, university English courses closed and the humanities continuously culturally downgraded given the impact the creative industries have both socially and economically (around £115 billion a year). Maths is important – I did it myself for A-level – but it is not the ‘silver bullet’ Sunak promises it is.

Rather than worrying about whether enough 17-year-olds can multiply imaginary numbers expressed in polar form, Sunak should instead focus on policies that are actual vote-winners, like serious childcare reform (which has sadly just been shelved). After all, people don’t need to have studied maths to 18 to be able to understand the severity of NHS waiting lists, or the difference between a 2 per cent pay rise and 11 per cent inflation. Neither do they need maths to understand the huge increases to their mortgages and gas bills or the fact that the 40,000 nurses who quit last year equates to one in nine. Unless Sunak addresses these, rather than throwing a dead cat on the table, then he risks coming across like David Brent: smug, self-satisfied and hopelessly out of touch.

Comments