In the Kunsthalle Praha, a smart new gallery in Prague, a Scottish professor from UCLA called Russell Ferguson is trying to explain to me the meaning of bohemia. Like a lot of fashionable buzzwords, it’s surprisingly difficult to pin down. Is a bohemian an artistic rebel? Or merely a pretentious layabout? Ferguson is an expert on the subject, and even he can’t quite sum it up.

However, unlike most academics (and most journalists, for that matter) Professor Ferguson isn’t content to just sit around and chat. As well as writing a book about bohemia, he’s mounted an exhibition about bohemians here at the Kunsthalle – and after he’s shown me round, I have a far better sense of what bohemianism is all about. ‘Bohemia – History of An Idea (1950-2000)’ shows how bohemians have shaped the cultural landscape of our lifetimes, and how, after a century of cultural supremacy, their time has passed.

Ferguson’s book (which shares the same name as his Kunsthalle show) contains the best definition of bohemia I’ve found so far: ‘A commitment to art in all its forms, sexual freedom, the embrace of alcohol, drugs and intoxication in general, hostility to work and conventional ambition.’ Apart from the commitment to art (most of us, I fear, are quite happy simply scrolling through our iPhones) what’s notable about this definition is how these values have spread from the fringes of society to the mainstream.

The first thing I learn from Ferguson’s enthralling exhibition is that I’ve been lured here under false pretences. I knew Prague was the capital of bohemia, the historic forerunner of the Czech Republic, so I always assumed this must be where bohemianism started out. Not at all. Turns out the word is a complete misnomer. The term bohemian was coined in Paris in the nineteenth century to describe a certain lifestyle – a dissolute revolt against the dreary conformity of bourgeois life. Bourgeois Parisians associated this liberated lifestyle with gypsies, and they thought gypsies came from bohemia. They were wrong on both counts, but the name stuck.

Sure, most of them were idle dilettantes – but at least they knew how to have a good time.

In 1851, the French writer Henri Murger wrote a series of popular short stories called Scenes of Bohemian Life, and by 1852 the term had already become common usage, as demonstrated in a splendidly splenetic rant by Karl Marx. In The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, Marx rails against these ‘vagabonds, discharged soldiers, discharged jailbirds, escaped galley slaves, swindlers, mountebanks, lazzaroni, pickpockets, tricksters, gamblers, brothel keepers, porters, literati, organ grinders, ragpickers, knife grinders, tinkers, beggars – in short, the whole definite, disintegrated mass, thrown hither and thither, which the French call “la bohème.”’

The thing that really put ‘la bohème’ (aka bohemia) on the map was the 1896 opera of the same name by Puccini. Based on Murger’s stories, it cemented the romantic ideal of the impoverished artist, toiling in a garret, rejecting the tiresome constraints of regular employment and family life.

In actual fact, although being bohemian in Belle Epoque Paris usually involved a certain amount of artistic endeavour, it generally had just as much to do with drinking absinthe and hanging out with can-can girls – a fin de siècle forerunner of Sex and Drugs and Rock & Roll. Poets like Rimbaud and Verlaine lived a version of this myth, establishing Paris as the go-to place for literary emigres like Ernest Hemingway, George Orwell and James Joyce.

Ferguson picks up the story in Paris in the 1950s. After the Nazi occupation and its austere aftermath, the city was springing back into life. Albert Camus and Jean-Paul Sartre were the poster boys of this renaissance, but Ferguson focuses on less famous figures. bohemia is about wannabes, not superstars – it’s really all about the artistic lifestyle, rather than the art itself.

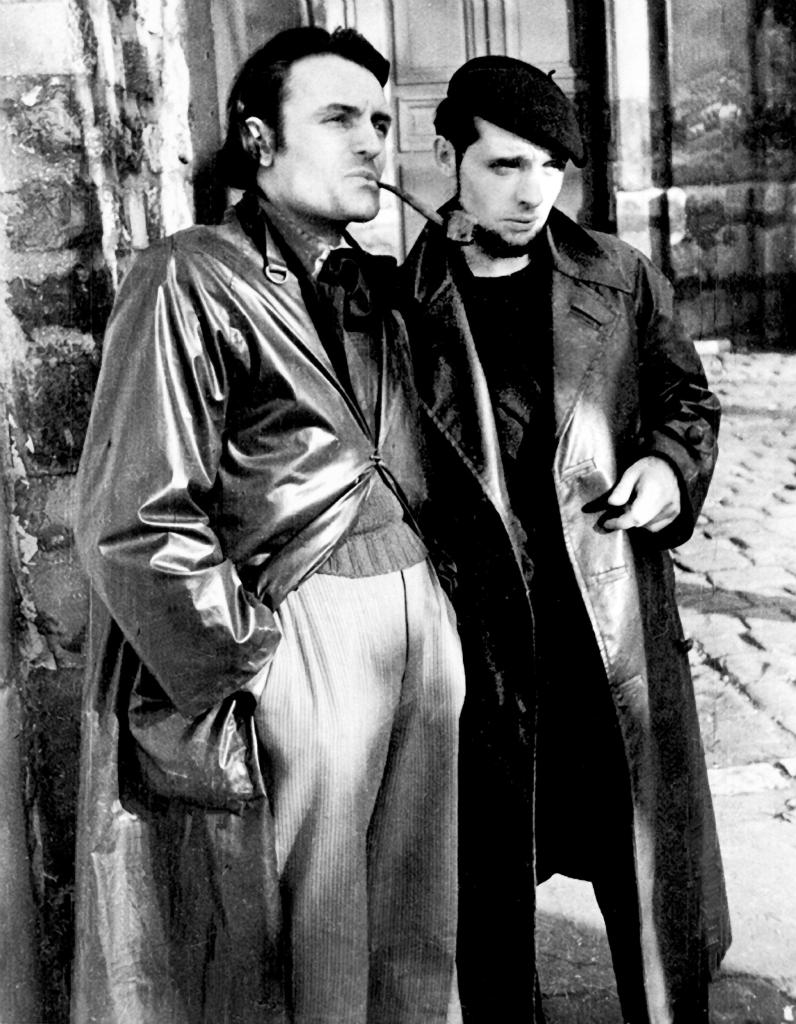

Looking at Ferguson’s moody photos of Parisian bohemians, in their boiler suits and donkey jackets, what’s notable is how familiar they seem – not because their obscurantist art endured but because the look they created became ubiquitous. ‘Ne travaillez jamais!’ (never work) was their Situationist battle cry, but, oblivious to irony (self-awareness was never their strong point), they purloined the rugged streetwear of the working man.

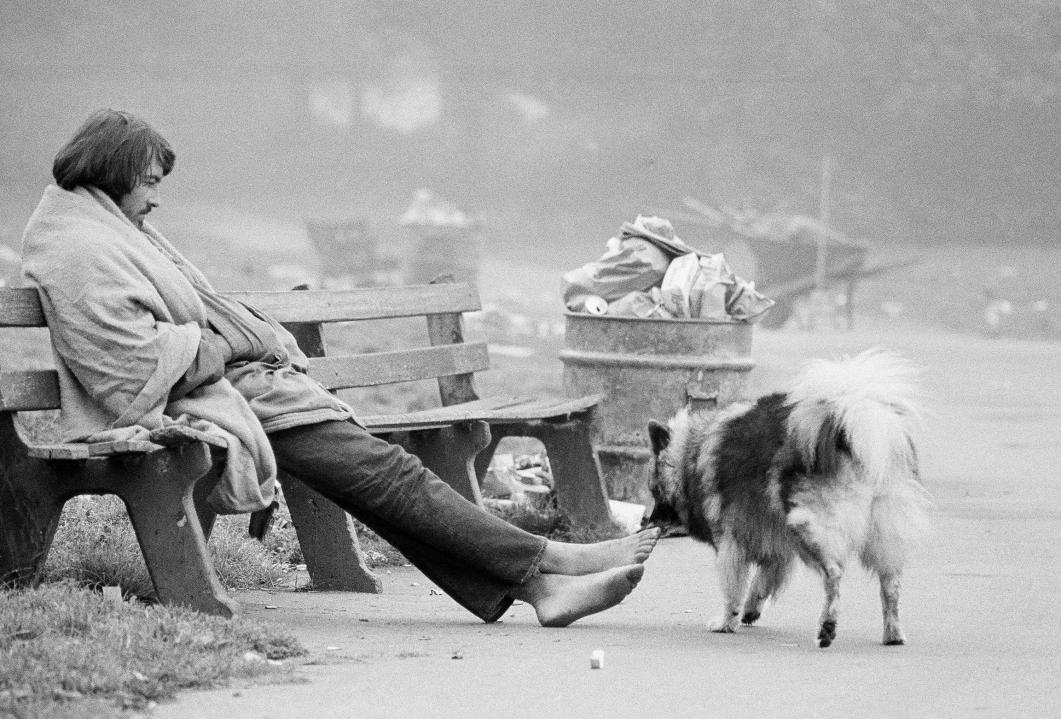

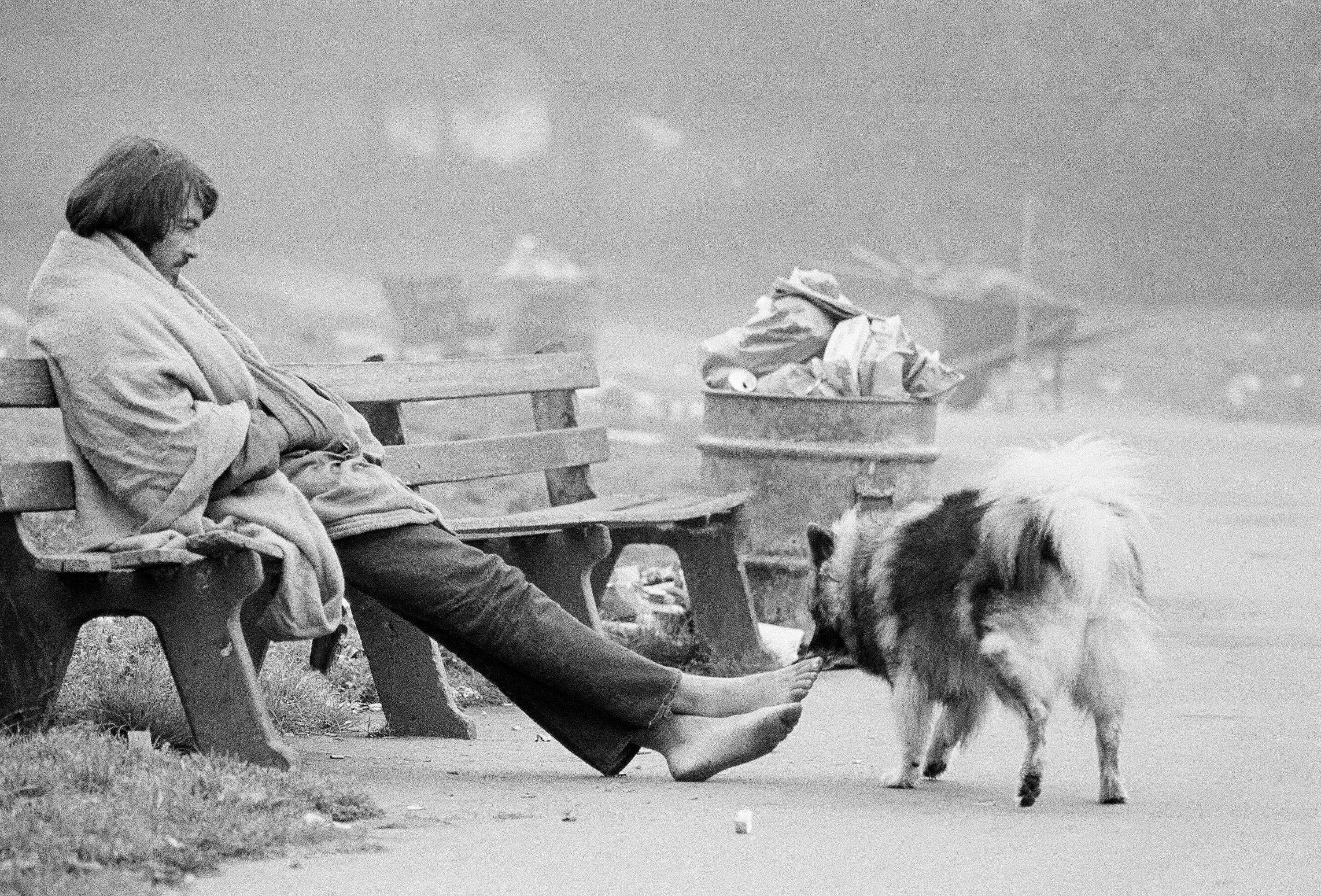

A lifetime later, that construction worker chic has spread far beyond the Rive Gauche. At first it was the uniform of middle-class students, then thirty-something hipsters. Today, virtually everyone of working age affects this pseudo-proletarian garb. Thanks to those Parisian bohemians, and their Beat Generation acolytes in New York, millions of middle-aged men and women have forsaken the well-cut clothes of yesteryear, and now traipse along our city high streets clad in shapeless overalls and cargo pants.

Bohemia’s potent influence has spread way beyond street fashion. Ironically, for grungy renegades who always scorned home ownership, bohemians have played a leading role in urban regeneration. Ferguson concentrates on the bohemians who revived New York’s SoHo neighbourhood, but he could have found examples of this phenomenon in countless other cities.

Unlike the rest of us, bohemians don’t mind living in neighbourhoods awash with drugs, crime and graffiti. Attracted by cheap rents (or in some cases, no rent at all), they appropriate rundown buildings, transforming post-industrial netherworlds into hip and happening inner-city enclaves.

This grungy ambience attracts fashion-conscious ‘creatives’ – people who work from nine to five but still like to think of themselves as edgy. That influx of young professionals creates a market for chic gallerists and restaurateurs, and then the developers move in, converting those old warehouses into luxury apartments. Priced out by these entrepreneurs and their well-heeled clients, the bohemians move on to revitalise the next wasteland. Bohemia isn’t just a cultural catalyst. It’s an economic enzyme, too.

This gentrification process has been replicated all around the world, most dramatically in East Berlin after the Wall came down. I was there for some of it, and it was thrilling. At first, anything seemed possible – the creative opportunities were endless. Bohemians turned a derelict department store into Berlin’s coolest arts centre, Tacheles – they turned a redundant factory into Berlin’s hippest nightclub, Berghain. But after the global brands caught on, Berlin became increasingly homogenous, just another international metropolis with all the same chainstores.

Something similar happened here in Prague. In the 1990s, if you were prepared to rough it, you could live cheaply and do your own thing, so bohemians flooded in. ‘Convention was overthrown, and people were looking for a new way of being,’ says Ivana Goossen, director of the Kunsthalle. ‘The new normal was yet to be discovered – it was a fantastic time for experimentation.’

However those halcyon days could never last. The early nineties was merely a brief interregnum between the collapse of communism and the triumphant return of capitalism. After the artists came the sightseers and stag parties. Prague is still an exciting city, but it’s no longer extraordinary.

The Kunsthalle’s chief curator, Christelle Havranek, moved here from her native France in the early nineties. She’s lived here ever since. ‘There were many Americans, and people from all over Europe – it was easy to live with nothing,’ she tells me. ‘I met true bohemians in Prague – it was really inspiring.’ She lived the bohemian dream, moving to a foreign city to reinvent herself. Like all bona fide bohemians, she’s a cuckoo in the nest.

Cities like Berlin and Prague confirm that bohemia is a passing phase in the evolution of a city. It’s especially visible in the former communist capitals of eastern Europe, but we’ve all seen something like it in western cities too. Bohemians turn barren slums into buzzing districts, then those districts become bland and corporate, and the bohemians disappear.

So why is bohemia fast becoming a thing of the past? Partly because modern developers are redeveloping brownfield sites at an ever-faster rate, but mainly because of the all-pervasive power of the internet. ‘The squeezing of real estate in every big city has made it increasingly difficult to find the space for the traditional bohemian society,’ says Ferguson. ‘The commodification process is really fast.’

Big business has always been adept at turning subcultures into commodities, but that colonisation used to happen gradually, giving alternative movements time to grow. In our brave new online world, everything is instantaneous. Bohemia was like a speakeasy with a strict door policy. You had to be in the know. Now everyone has a smartphone, there are no secrets anymore, and no insiders. Bohemia used to move around, from Paris to New York to San Francisco. Now it’s everywhere all at once, and nowhere at all.

Bohemia has always contained the seed of its own destruction. Neither the nihilism of Punk nor the idealism of the Hippies was any match for market forces. Both of these movements were emasculated, and eventually eradicated, by commercial interests. For every generation, sooner or later, the dream turns sour. Bohemia is ephemeral and so it soon tips over into nostalgia. To be bohemian is to be young and free with your whole life ahead of you. It’s about living for today, which is why, in the end, it’s bound to fail.

‘I had a love affair with a bohemian man,’ reveals Christelle Havranek. ‘I realised there’s no future, there’s absolutely no future, with someone like that. It’s fun – you do what you want, you don’t think about tomorrow, but I was not as bohemian as he was, and one day I started thinking about having money, having a family, having a place to live, and that was the end of it.’ ‘Maybe each of us has a bit of a bohemian inside of us,’ says Ivana Goossen. We carry that memory with us, into the autumn of our lives.

It’s easy to mock the paradoxes and pretensions of bohemia. Bohemians refused to participate in mainstream society, but they didn’t want to drop out altogether. They weren’t interested in self-sufficiency – they didn’t go off-grid or grow their own food. They tried to cherry-pick the perks of capitalism – they wanted to have it both ways (as Ferguson says, they refused to work but they didn’t refuse to take the subway). Yet even though their relationship with society was parasitical, they invigorated urban life, just as scavengers sustain the food chain. Sure, most of them were idle dilettantes and they eventually grew out of it – but at least they knew how to have a good time.

‘The rhetoric around this period is quite fascinating,’ says Ferguson. ‘It’s almost unbelievable – the confidence that people had that you could change society by taking enormous quantities of drugs.’ But, at its best, there was more to it than that. Bohemians fought for Gay rights in the 1970s and AIDS awareness in the 1980s. Under communism, bohemian nightlife became an underground resistance movement – a space where people were free to be themselves.

‘Is it possible to be bohemian online?’ asks Christelle Havranek. ‘To me, it’s about physical togetherness. It’s about drinking together, telling stories to each other.’ As we retreat into cyberspace, and vanish into our individual virtual bubbles, bohemia has become a byword for the communal life we left behind.

Comments