Voters in Spain’s general election on 23 July have a clear-cut choice. They can choose to continue with the left-wing coalition currently in power or they can replace it with a staunchly right-wing government.

Since 2019 Spain has been governed by a minority coalition consisting of PSOE, Spain’s main left-wing party, with 120 seats, and Podemos, further to the left, with 35. With a total of only 155 of the 350 seats in the national parliament, in order to pass legislation the left-wing bloc has had to seek ad hoc support from various regional parties, including Basque and Catalan separatists.

Many want to punish Sánchez for pardoning the Catalan separatist politicians

Many voters will prefer the right-wing combination consisting of the Partido Popular, Spain’s main right-wing party and, further to the right, Vox. The Partido Popular currently has 89 seats, and Vox 52. But polls suggest that next Sunday’s election will see a substantial increase in the right-wing bloc’s total of 141.

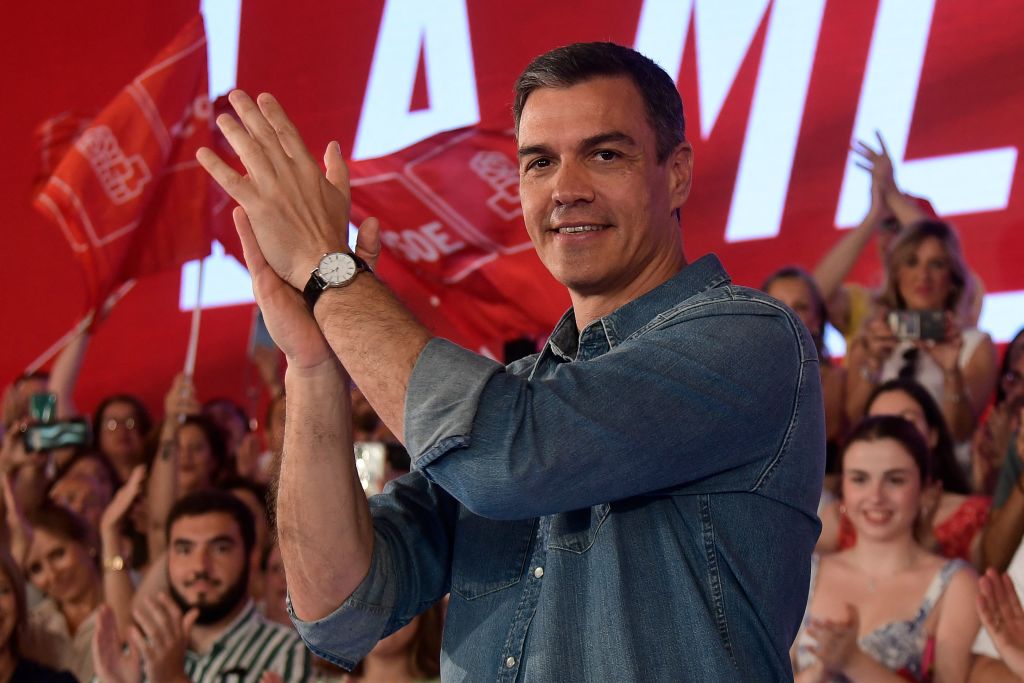

In an attempt to stem the rise of the right, Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez is emphasising his administration’s achievements. The minimum wage has been raised by 47 per cent and, to relieve ‘severe poverty’, a national minimum income has been introduced and pensions increased. Meanwhile, the economy is one of the eurozone’s better performers. And tensions between Madrid and Barcelona have eased thanks to Sánchez’s conciliatory approach to Catalan separatists.

But that conciliatory approach has angered many voters. They want to punish Sánchez for pardoning the Catalan separatist politicians who were jailed after their illegal referendum and declaration of independence in 2017. Similarly, many Spaniards will never forgive Sánchez for relying on the support of the Basque separatist party, EH Bildu, led by a convicted ETA member. Another major blow to Sánchez’s popularity – and the left’s standing in general – was a botched law on sexual consent. Although intended to protect women, over a hundred sex offenders were released from prison because of mistakes in the way offences were redefined.

It was no surprise, then, that the campaign began with the right-wing bloc, buoyed by its success in May’s local and regional elections, ahead in the opinion polls. Signs that the left might close the gap soon emerged, however and Sánchez hoped to gain further momentum in the only televised debate with Alberto Núñez Feijóo, leader of the opposition Partido Popular. In the event, however, Feijóo emerged stronger from the face-off between the two rivals to lead the next government.

The ‘debate’, though, was a disgraceful spectacle. For painful stretches of the two tedious hours that it lasted both politicians were talking at the same time. Neither could hear the other, and viewers couldn’t make out what anyone was saying. Sadly, it has become normal in Spain for politicians to talk over their opponents rather than to them.

When he did manage to make himself heard, Sánchez reproached Feijóo for his willingness to govern with Vox, a party which he claimed is homophobic, xenophobic, sexist and far-right. Feijóo responded by pointing to his rival’s reliance on votes from the Basque and Catalan separatists. And what, he asked, could be more harmful to women than the early release of dozens of rapists from prison?

In any case, Feijóo pointed out, there was a simple way for Sánchez to avoid Vox entering a government: if Feijóo’s party won most seats, albeit not a majority, then Sanchez’s socialists could abstain at the investiture, allowing Feijóo to govern alone. If Sánchez agreed to that, then, in the event that it was the socialists who won most seats, he would gladly reciprocate, allowing Sánchez to govern without the extremists to his left. Sánchez, mindful of the polls, wisely declined the invitation.

Before the debate, a YouGov survey gave Sánchez’s PSOE only 108 seats and Sumar (the party even further to the left now has a new name) 36: a total of just 144 for the left-wing bloc. Meanwhile it gave the right-wing bloc a total of 176 (Partido Popular 131, Vox 45) – the bare minimum for an absolute majority. That figure may have risen slightly since the debate. But YouGov points out that the battle for some seats will be very close: tiny shifts may be decisive. The problem for the right-wing bloc is that if it falls even, say, half a dozen seats short of the 176 needed for an absolute majority, it may be a case of ‘so near and yet so far’. The Basque and Catalan separatists certainly won’t be helping their enemies over the line.

With a week still to go, only one other thing seems certain: whichever bloc governs Spain for the next four years will face fierce opposition.

Comments