Much heartened by the barrage of criticism I’ve been receiving from both Spectator and Times readers, I’m returning to the subject of Coutts’s customer selection. I’ve learned over the years how to spot the emergence of a herd opinion, not just by the volume of shouts but also by how members of the herd begin copying and repeating – often word for word – each others’ phrases; and what we now call ‘memes’ take shape. My experience is that when public sentiment begins to attract these characteristics, it is almost always wrong. I never forget the advice of my late grandfather, Squadron Leader Leonard Littler: ‘Whenever I hear of a great wave of public indignation, I am filled with a massive calm.’

Profit-making companies have been making very public ethical stands since commerce was invented

I’ve especially relished the spectacle of my own journalistic colleagues gathering up their skirts in moral horror at the idea that someone might be so indiscreet as to leak information to a journalist, and the meme that even a lowly bank clerk would be sacked for doing so. Indeed they would. A lowly bank clerk might be sacked for dressing sloppily, persistently arriving late for work, or having alcohol on his breath after lunch. A bank manager would be safe from dismissal on such counts.

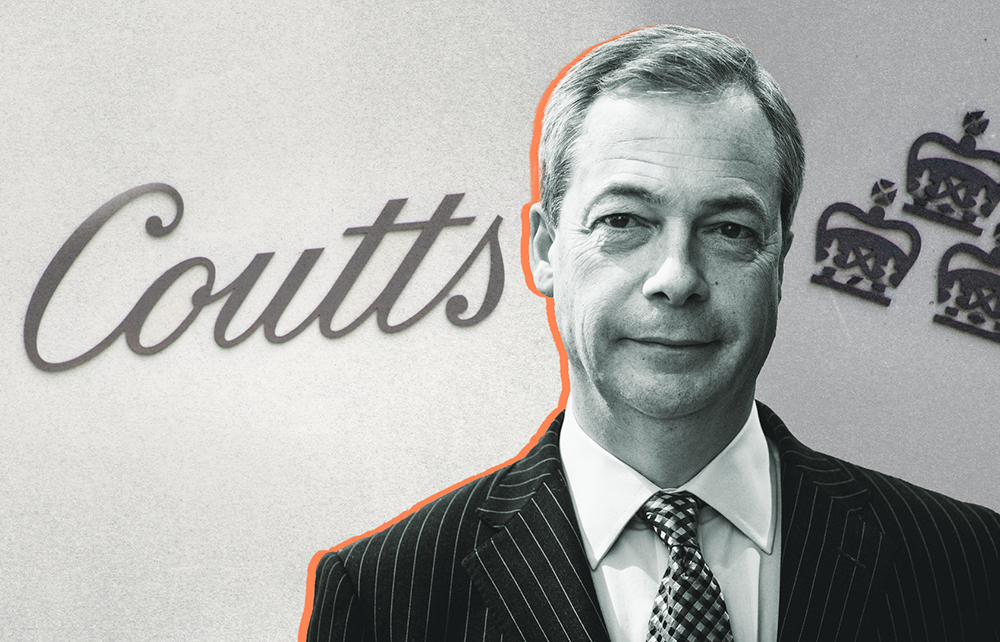

Anyone who has spent years attending dinner parties or pub gatherings in a respectable English country town will greet with a smile of recognition the news that local managers in the banking, legal or medical profession have been known to gossip about their clients’ private affairs. But oh how we puff with fury at the outrage that Nigel Farage, that soul of respectfulness in his own utterances, should have been the victim of loose talk! How it pains us that this unfortunate man, a stranger to self-publicity and seeking only the shadows, should have suffered public exposure! Farage, meanwhile, who lives, moves and exists through noise, can doubtless hardly believe his luck.

I move to an aspect of the affair that the more serious commentary has increasingly highlighted. Such commentary is, I must say, quite persuasive on first reading; and you will not read far without encountering the word ‘woke’. A fashion in the business world is disapproved of: the publicising of corporate moral stances in order to ingratiate a customer-facing business with its clients. I too grind my teeth at some of these: and many are infuriating. Companies ‘greenwash’ to show their environmental concern. Other bodies (like the RSC in Stratford) terminate their partnerships with BP to demonstrate their environmental concern. Businesses pay Stonewall to advise them on ‘workplace equality’ and award gold, silver and bronze medals in their ‘diversity champions’ programme. Companies attend seminars on pronouns. Galleries seek to ‘decolonise’ their exhibit notes (or even their exhibits)… and so on. A lot of nonsense, much of it.

But hold on. Are we saying we don’t think corporate entities should take public stands on political or moral issues? Or are we saying we don’t like the stands that some of them take? There is a world of difference between these two propositions; but with a sigh I approach again the probably hopeless task of asking readers to see that sweeping statements of principle, though they may sound compelling, can prove too strong; and before making them we should consider where the logic might lead.

To say that the pursuit of moral causes is somehow ‘wokery’ and no business of a commercial organisation is far too strong. Profit-making companies have been taking very public ethical stands since commerce was invented. On 19 March 1909, William Cadbury announced a boycott on his company’s long-standing purchase of slave-grown cocoa from São Tomé. He was sneered at in newspapers for virtue-signalling. Fry’s and Rowntree’s joined Cadbury, and then the Americans too. Finally the Portuguese government ended slavery on the island.

In Britain, the Co-operative Bank has for decades advertised its commitment to ‘ethical’ investment (and gained many customers thereby). I cancelled our joint account with HSBC because I dislike their collusion in Beijing’s policies in Hong Kong, and I don’t regret it. The Body Shop has done much to make us think about cruelty in animal testing.

When commercial institutions seek to associate themselves with good causes or dissociate themselves from bad ones there will often be mixed motives. One may certainly be self-interest: a desire to attract or hold on to customers. But remember businesses are run by human beings who may have strong beliefs and political or moral preferences of their own. There will be individuals with whom it may stick in the throat, personally or corporately, to do business. Public indignation in these cases will vary. Peter Oborne, while disapproving of the exclusion of Farage, makes the point that a number of prominent Muslim activists and organisations have been denied bank accounts and the media has never taken any interest at all in their ‘right to free speech’. ‘Nobody cares,’ he writes.

Perhaps such decisions were justified – I don’t know – but I can feel readers switching off as I write about excluded Muslims, muttering: ‘That’s different.’ It isn’t: not if you want to maintain a right to an account with a particular bank as a general principle. What chance Farage will take up these Muslims’ cause?

Conservatives (I used to think) believe in capitalism as a force for moral good as well as economic growth. We admire free–market philanthropy. We see the best business leadership as guided by a moral as well as commercial compass. We think values-free corporate strategies discredit free enterprise. Socialism, meanwhile, if it tolerates free enterprise at all, sees it as a necessary evil and morally blind, to be regulated therefore by the state. Well, fair enough: in the Coutts affair the statists have won. But please do not call them Conservatives.

Comments