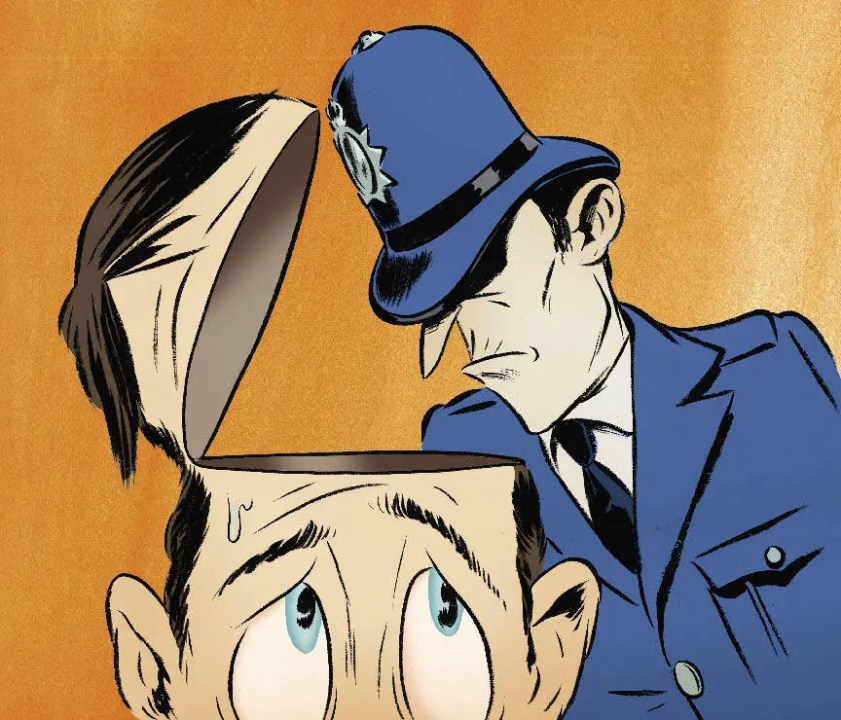

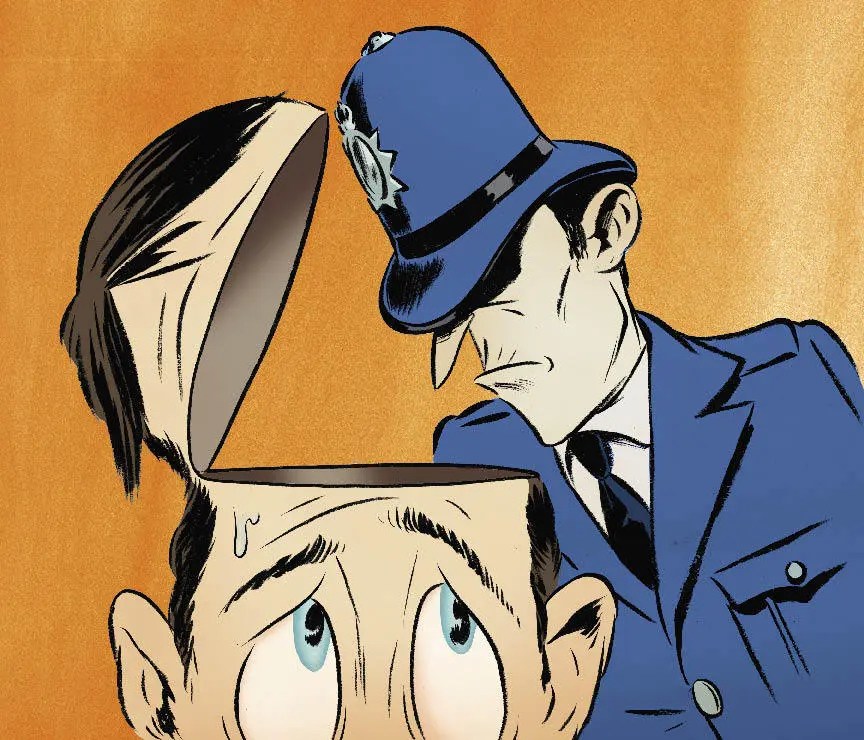

Imagine a policeman feels your collar and tells you you’re nicked because someone has reported you for telling off-colour stories in a corner of the rugby club bar, or for making sick jokes at a party to a group of friends which the authorities disapproved of? Something as positively Stasi-esque wouldn’t happen here, would it? Perhaps not in that form, at least yet.

How have we got to the position where we are policing private speech for politeness?

But change the scenario to the online world, and something disconcertingly like it is already in place. This week it was announced that six ex-members of the Metropolitan police now face charges which could result in them being sent down for up to six months because they had allegedly shared among themselves racist jokes and derogatory comments. The messages had appeared on WhatsApp between 2018 and 2022. These messages, it seems, were then passed to the BBC. The BBC ran the story on Newsnight, the Met investigated and … well, the rest was history.

The case is ongoing, and we must be careful not to prejudge. But that these charges were brought at all ought to worry all Spectator readers concerned for liberty, despite the fact that (one hopes) no one would join a group that would share the sort of content alleged.

For one thing, this wasn’t a case of public offensiveness. Everything allegedly took place on a WhatsApp group that you or I couldn’t read even if we’d wanted to. This is as near as you can get on the internet to an intimate group of friends, and certainly not worth the resources of an overstretched Met.

Secondly, the mention of the Metropolitan police connection is a bit of a side issue anyway. Granted, this sort of stuff would be unacceptable within a police force. Yet if you read the story you will see that all the accused had left the organisation well before the time period concerned. It is also worth pointing out that at least some of the alleged material might have been scabrous and in very bad taste, but would not actually have been illegal at all if said offline.

How have we got to the position where we are policing private speech for politeness? The answer is the innocent-sounding section 127 of the Communications Act 2003, under which the men were charged, and which criminalises anyone who ‘sends by means of a public electronic communications network’ anything ‘grossly offensive or of an indecent, obscene or menacing character.’ This section is a classic example of inadvertent but sinister mission creep. It first appeared in 1935 to deal with yobs who took advantage of the fact that no charge was made for calls to (invariably female) telephone operators to tell them about their adolescent fancies. Not surprisingly, it applied simply to telephone calls (later being extended, more pretentiously, to ‘public telecommunications’ systems). In 2003, in what was almost certainly seen as an exercise in technological tidying-up, the word ‘electronic communications network’ was substituted, thus by a side-wind making an enormously wide crime out of blue language anywhere on the internet, from Google’s public website to an intimate email.

Unfortunately, this new catch-all crime, with its impressively wide reach (made still wider because the question of what is grossly offensive is usefully open-ended) immediately became beloved of police and prosecutors. They were, after all, only human. Inundated as they were with regular complaints by puritans, activists and people with axes to grind, they now had an easy way to appease such complainants. They could either prosecute if they wanted to make an example, or tell people that if they did not pipe down their homes would be raided and they would be arrested. Either is bad: too often it has been the former. This week’s case is not the first time private speech has been targeted in this way. Last year a man received a suspended prison sentence when he made a video in appalling taste about the Grenfell Tower disaster at a private party his own home and sent it to a closed group of his friends.

What now? To anyone with the remotest instinct for free speech, or for that matter personal privacy, the answer is a no-brainer. Section 127 must go. Whatever we do about public distribution of nasty material (and there are plenty of offences available to deal with this), the state has no business punishing consenting parties for what they say to one another in private, offline or online. Even the official law reform body the Law Commission, a slightly precious organisation not known for its enthusiastic attachment to liberty, said so a couple of years ago.

Unfortunately this is easier said than done. In January this year the government, having previously suggested it might do the right thing and get rid of this legislative cuckoo, changed its mind. No doubt following discreet lobbying from authorities who find it just too convenient a tool to keep uncooperative citizens in order, it announced it wanted to retain it, saying disingenuously that limiting what people could say online was necessary to protect the vulnerable from abuse. (No, me neither.)

Nevertheless, the Home Secretary should now think again. A carefully-directed commitment to protect the freedom of the ordinary man or woman would be a nice addition to the programme of a Tory party that clearly needs some good manifesto ideas.

More to the point, if there is a change of government next year, the continued existence of section 127 will present a very clear and present danger. A Labour administration would, one suspects, be very happy to see prosecuting authorities pursuing those who attack its policies on immigration, asylum, trans rights or equality as purveyors of gross offensiveness. The present situation would suit Labour just fine. Suella, you have been warned.

Comments