The Red Shoes, Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s 1948 film about a ballet and its company, is 75 this month, and its birthday is being marked with great fanfare. From October to December, the BFI is putting on a major retrospective of the films of Powell and Pressburger, with an accompanying exhibition and nationwide screenings of The Red Shoes itself. A companion book to The Red Shoes by Pamela Hutchinson – stuffed with insight and background – is being published, as well as a lavish volume, The Cinema of Powell and Pressburger, complete with pictures and essays (almost love letters) about the late filmmakers from artists such as Tilda Swinton and director Joanna Hogg.

For Martin Scorsese it was ‘film as music’, ‘the movie that plays in my heart’

Powell and Pressburger named their production company The Archers. And they hit the bullseye with an extraordinary number of films: The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943), A Canterbury Tale (1944), I Know Where I’m Going! (1945), A Matter of Life and Death (1946), Black Narcissus (1947), and The Tales of Hoffmann (1951). Six of their movies feature in the Sight and Sound Greatest Films of All Time poll, a number matched only by Hitchcock. But where does The Red Shoes sit in the cinematic pantheon? At its first studio screening, executives from Rank were baffled and even appalled, dismissing it as an ‘art movie’ and giving it, initially, a strictly limited release. Kenneth Tynan spoke of its ‘costly and inelegant vulgarity’. Others, like the great film critic Dilys Powell, noted its dazzling experimentalism. For Martin Scorsese it was ‘film as music’, ‘the movie that plays in my heart’. In lists of the most-admired British movies, it nearly always comes in the top ten. Rank and Tynan, you can conclude, perhaps got it wrong.

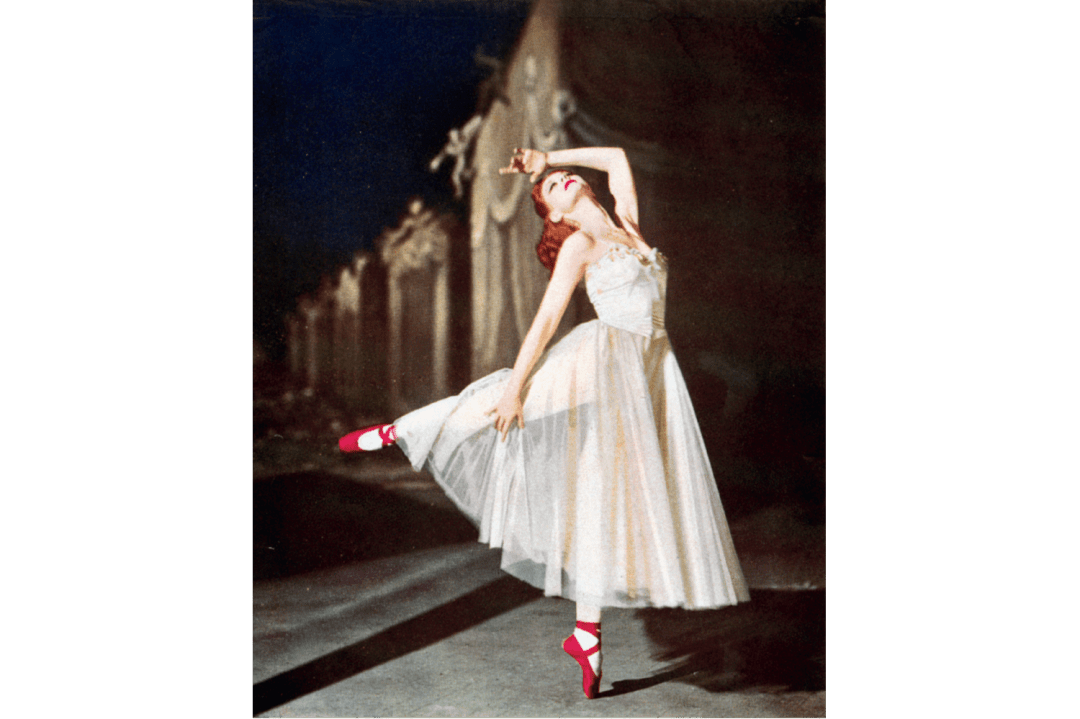

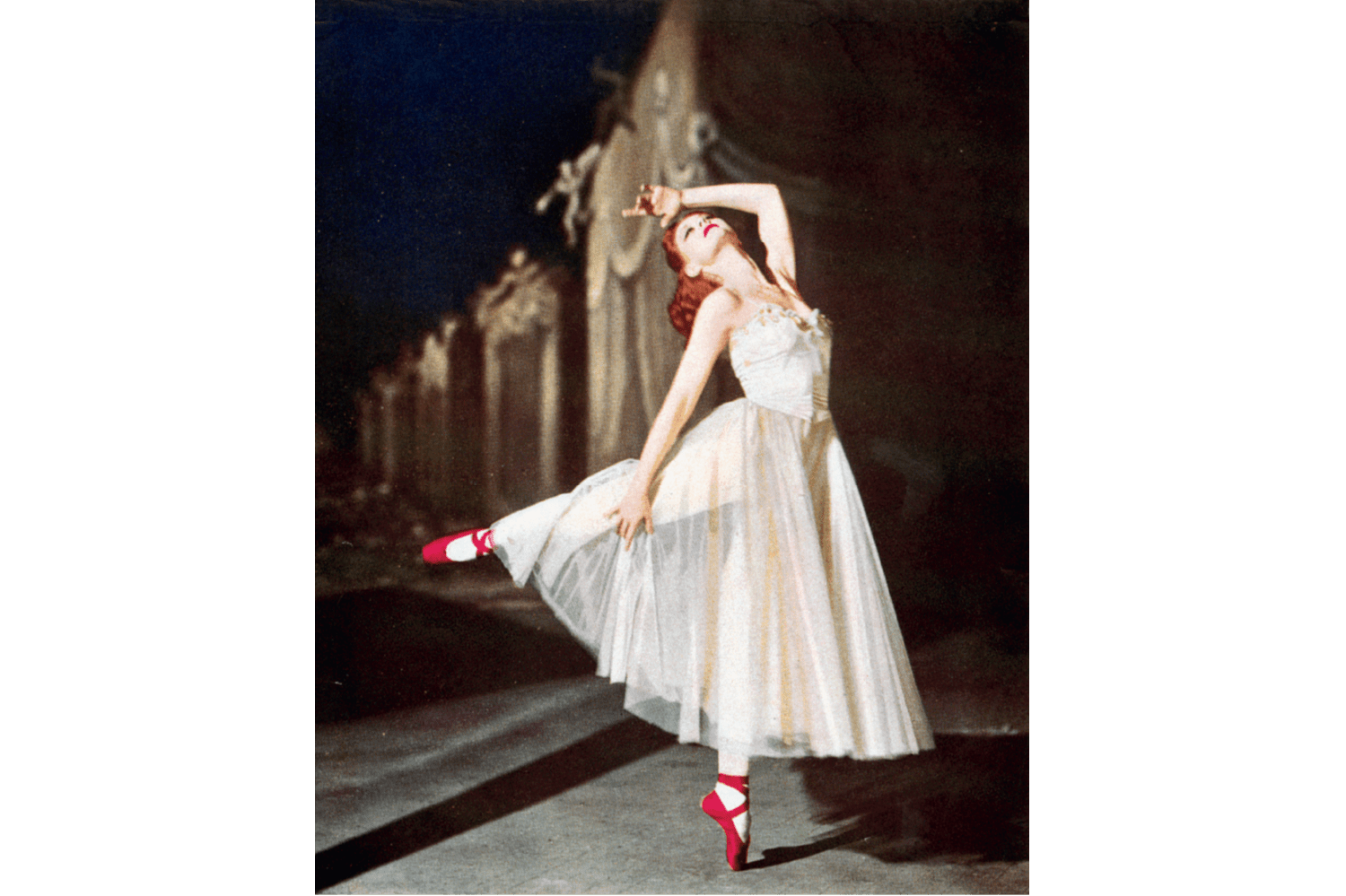

The two stories The Red Shoes tells have a myth-like clarity. First there is the ballet itself, based on Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tale about a girl who, enraptured by a pair of red shoes, makes the mistake of putting them on, only to find they have a frenzied life of their own. The shoes dance her in an unstoppable whirl to an exhaustion (and isolation) so profound she chooses to chop off her feet (and will later die) rather than give in to the delirium.

The second, outer story is of a modern, international ballet company, and a young dancer Vicky Page (Moira Shearer), plucked from corps-de-ballet obscurity to wear the Red Shoes by impresario Boris Lermontov (Anton Walbrook), the charismatic but tyrannical director of the company who vows to make her ‘the greatest dancer the world has ever known’. But personal life intervenes in the shape of young ballet-composer Julian Craster (an over-ripe Marius Goring) whose destiny is inseparable from her own. Their love affair and marriage provoke a rage worthy of Greek gods in the jealous Lermontov, for whom anything but dedication to art is a betrayal. ‘The dancer who relies upon the doubtful comforts of human love will never be a great dancer,’ he hisses. Neither Julian, Lermontov nor the Red Shoes will let Vicky go.

Seventy-five years on, The Red Shoes’s magic is undimmed. It feels less quaint or dusty than many films half its age, and nearly all the Archers’ arrows hit home. Designed by the painter Hein Heckroth, it has a Matisse-like gorgeousness of colour and a soundtrack, by Brian Easdale, as far from the usual rum-ti-tum bombast of 1940s film scores as can be imagined. Life in it, you feel, is just as it should be. Covent Garden is still a fruit and vegetable market, the French Riviera (to which the ballet company decamps) looks as crisp as an art-deco tourist poster, and the artistes – in bracing hierarchy – are still summoned to work by hand-written memos (in English, French and Russian) pinned to the company noticeboard.

Today Lermontov would have been dismissed long ago for bullying, micro-aggressions and high-handedness

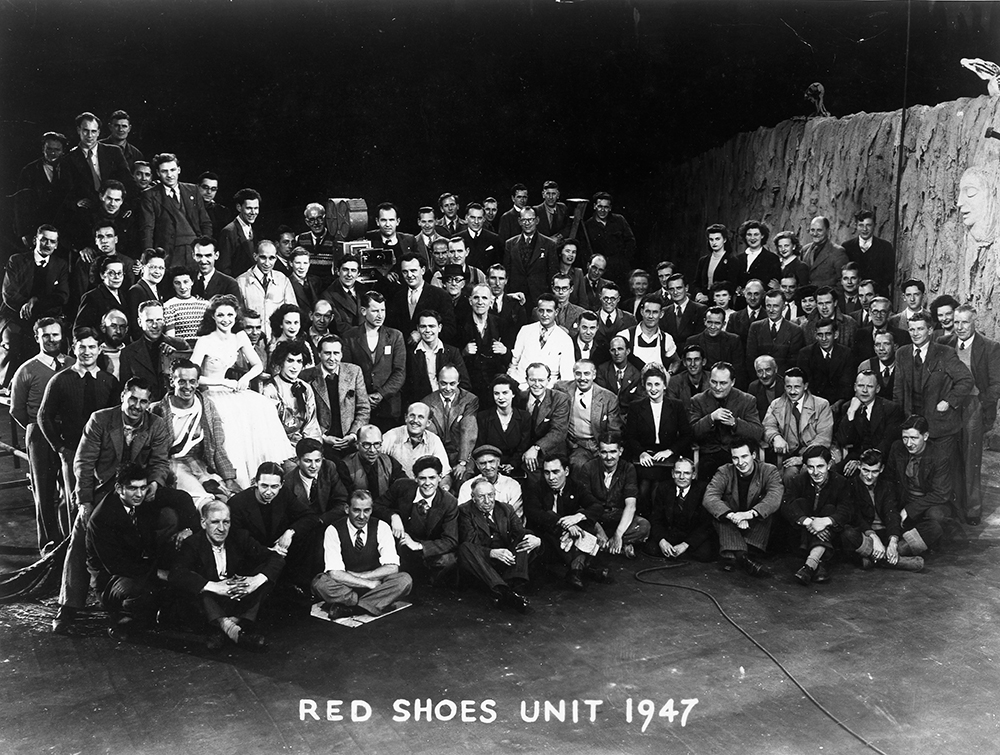

Yet what makes it so unfashionable – and thus so timely – is its depiction of Art with a capital ‘A’, and the supremacy of the demands Art makes on creators. Powell himself was explicit about this, describing the film as ‘a haunting, insolent picture, in the way it takes for granted that nothing matters but art, and that art is something worth dying for’. The Red Shoes, he said, was intended to be ‘a gathering together of my whole accumulated knowledge of the film medium – disciplined by music, enhanced by colour, with the very maximum of physical action’. It’s not only Powell’s ‘accumulated knowledge’ we get. In few films do you find such a sense of collaboration, of experts in their field – dance, visual art, costume, cinematography – working together so inventively at the top of their game.

In the 1990s, when I first saw the film, Michael Powell had recently died and there were several documentaries about him on television. They told of his struggles to get The Red Shoes made, his battles with Rank executives to get the right artists working for him, his refusal to compromise over the 17-minute modern-dress ballet he knew The Red Shoes needed at its centre. The NFT used to show it regularly, and you would come out of the cinema – straight from the catharsis of its ending – to walk along the South Bank in a dream. The film held out the possibility of a life dedicated to your craft, full of travel, love, sacrifice and passionate allegiances. Hutchinson, in her penetrating book, calls it (correctly) ‘a dangerous film to see at an impressionable age’, but it remains a young person’s movie nonetheless – one that chimes most strongly when your ideals are unsullied and your future, like the Red Shoes, appears to you in Technicolor.

Seeing it in 2023, it still thrills with its magic but is different and sadder, more a warning than a promise. Vicky, poised for flight, seems doomed from the outset. Lermontov appears less a real person and more like Art itself, mercilessly trashing its practitioners should they fall short of its demands. Only for Powell, with his sense of creative martyrdom, did this dark, tragic fairy tale seem to have a happy ending.

Would anyone die for art in 2023? Amid newly sanitised classics, quota-castings, politically driven awards, formulaically ‘progressive’ narratives and ‘stay in your lane’ restrictions, it seems doubtful many would fight for it at all. The ideals of The Red Shoes – ones to build a life on – seem to have been betrayed and dismantled by their very gatekeepers. One imagines Powell and Pressburger surveying the modern world and clutching their heads in shock.

It’s fascinating to compare it with last year’s Tár, Todd Field’s bonfire of the artist’s vanities, perhaps so essential to their creating anything at all. As for Lermontov, he would have been dismissed long ago for bullying, micro-aggressions and high-handedness. His stern prioritising of Art would seem unreasonable, elitist and a red rag to the #BeKind brigade. Whether this is a price worth paying for the new orthodoxy is up to viewers to judge. The clash of values in The Red Shoes leaves us with a dancerless ballet and a gutted work of art, its heart torn out but still staggering on regardless. Something for us to ponder this autumn, as we make our way along the South Bank and beyond.

Cinema Unbound: The Creative Worlds of Powell and Pressburger is at the BFI from 16 October until 31 December. New restorations of several Powell and Pressburger films will be released nationwide. The Cinema of Powell and Pressburger and The Red Shoes, by Pamela Hutchinson, are published by Bloomsbury.

Comments