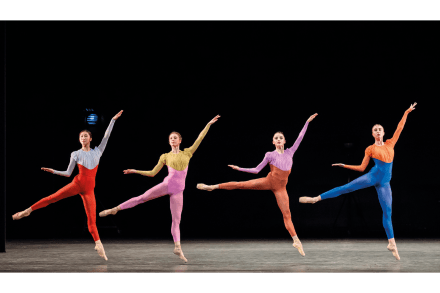

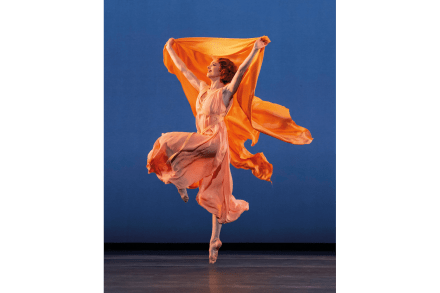

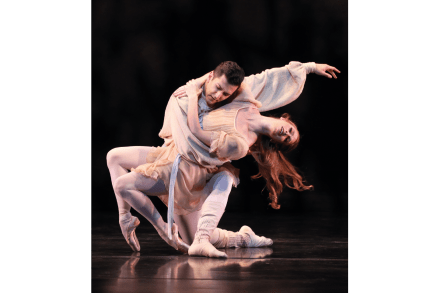

Rejoice at the Royal Ballet’s superb feast of Balanchine

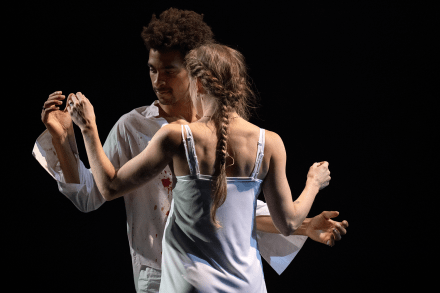

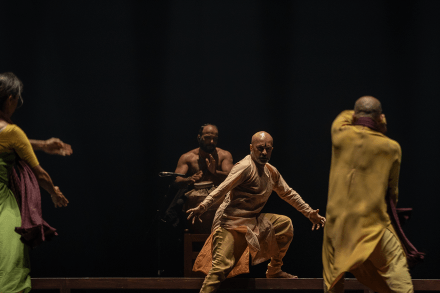

Any evening devoted to the multifaceted genius of George Balanchine is something to be grateful for, manna in the wilderness indeed, but the Royal Ballet’s current offering left me hungry for more. Three works were on the programme, all created in the early stage of the great man’s career, two of them widely familiar, none of them reflective of anything he created post-war for New York City Ballet. Are his executors reluctant to licence productions of later masterpieces such as Agon or Stravinsky Violin Concerto, or is the Royal Ballet fighting shy of their stylistic challenges? Gripe over, and let’s just rejoice in a feast of superb choreography at Covent