After opening its 2024/5 season with a run of Christopher Wheeldon’s candy-coloured, kiddie-friendly Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, the Royal Ballet gets down to business with a demanding but exhilarating programme of new work.

Newish, to be accurate; the evening’s only previously unseen piece is Joseph Toonga’s Dusk. Crystal Pite’s The Statement is eight years old and was previously seen at Covent Garden in 2021; Kyle Abraham’s The Weathering followed a year later; and Pam Tanowitz’s Or Forevermore has developed out of a duet that originated during the pandemic.

Dusk and The Weathering call for little comment. Both are well-crafted and safely generic, elegiac in mood and unassertive in theme. Dusk is notable for eloquent dancing by Marianna Tsembenhoi and Benjamin Ella; The Weathering has homoerotic undertones, culminating in a heartfelt solo for a bereaved Joshua Junker. Had they not been sandwiched between two masterpieces, both works could perhaps have made more impact: the performances were in any case altogether excellent.

The Statement could be an episode of the TV series Industry, as written by Kafka. Invisible voices broadcast a black comedy of corporate or government politics, in which unseen anonymous powers upstairs are threatening those in an office downstairs and the buck is being passed in fear and panic as nobody wants to claim responsibility for some atrocious unspecified decision. Four dancers (Kristen McNally, Ashley Dean, Joseph Sissens and Calvin Richardson, all brilliant) mime this downstairs drama in what could be described as signed body language, its implications both richly comic and psychologically telling, hilarious and chilling. Movements speak louder than words.

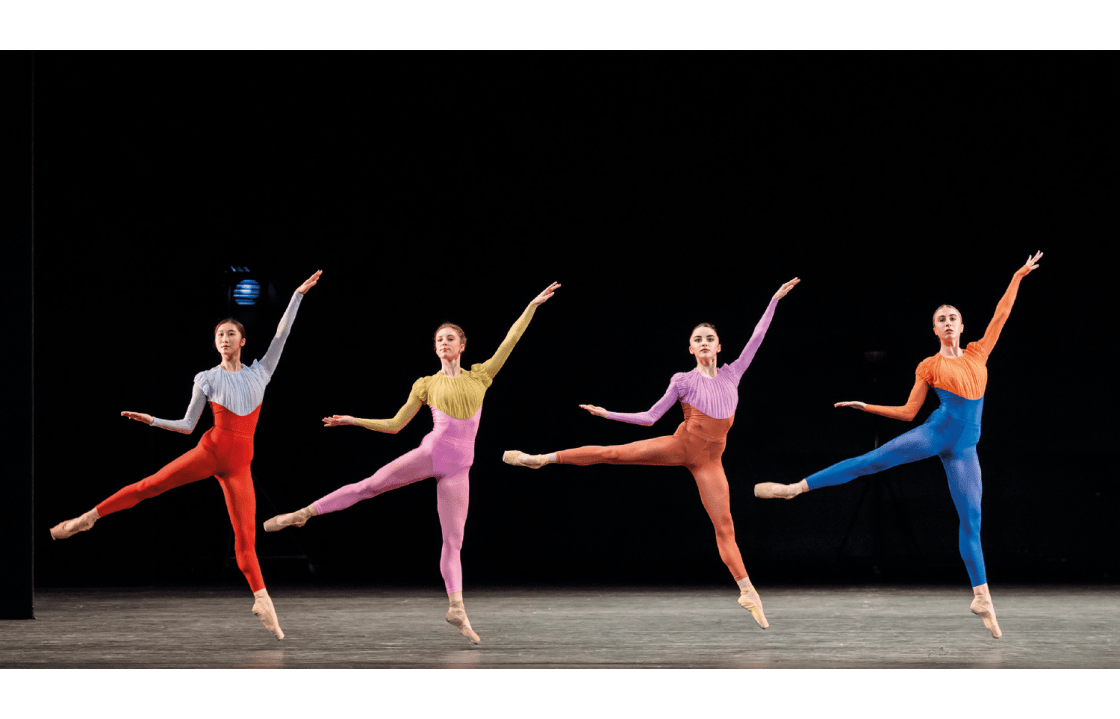

Or Forevermore is a marvellously ironic deconstruction of the conventions of classical ballet by somebody at one remove from them – the primary choreographic influence on Tanowitz is clearly the abstract aesthetic of Merce Cunningham, close collaborator of John Cage and Robert Rauschenberg, with Balanchine entering her creative mix later. Here, to the accompaniment of Ted Hearne’s magnificently exuberant crash of a score, Tanowitz inverts, undermines and interrogates all ballet’s weird obsessions, making strange its harmonious symmetries, its assumptions about gender roles, its coded gestures of courtly deference and ritual.

The piece opens with a curtain call taken by a ballerina dressed not in a tutu but a tracksuit; when that comes off, she is wearing a utilitarian running kit. Is ballet a sport masquerading as art, are dancers only athletes? What do any of their physical manoeuvres actually mean? On what terms – competitive or romantic, active or passive – are interactions taking place? Tanowitz explores such questions with supreme wit and imagination, offering answers through subtly inflected and precise steps and gestures that can be strikingly beautiful as well as electrically surprising – the snap of the unexpected is key. This isn’t satire or parody, but a fundamental critique of everything that the choreographers of Dusk and The Weathering take for granted.

It is superbly executed by a cast of 14, led by William Bracewell and Anna Rose O’Sullivan, who can never have danced better – and that’s saying something. Or Forevermore isn’t an easy affair. But the moment it ended I felt I had to see it again.

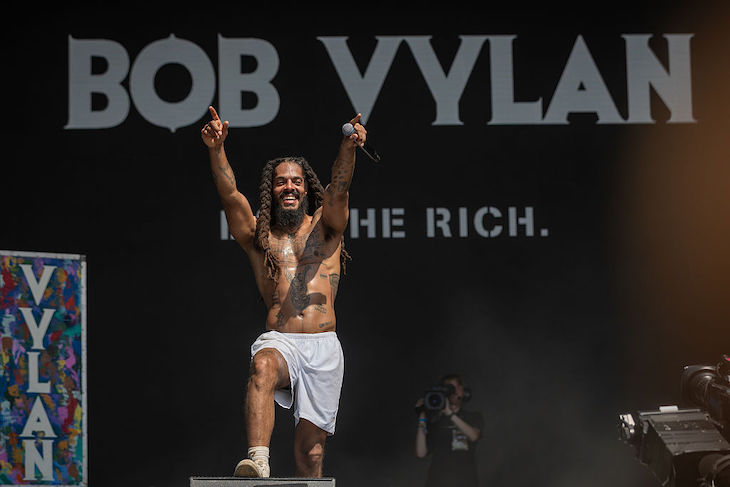

Luna, on the other hand, is something I would pay good money to avoid. Bafflingly billed as ‘inspired by the pioneering women of Birmingham’ – which sits at odds with the backdrop projections of the cosmos – this is the result of a collaboration between five choreographers, a children’s community chorus and Birmingham Royal Ballet. It’s the sort of diverse and inclusive affair that our benighted Arts Council drools over, but its six sections, linked only by hippy-dippy poetic quotations, amount to a dog’s dinner, incoherent at best and dreadfully boring at worst. Pity the poor dancers lumbered with such drivel. What a miserable waste of BRB’s increasingly straitened resources.

Comments