Sincere, serious and beautiful: Glyndebourne’s Parsifal reviewed

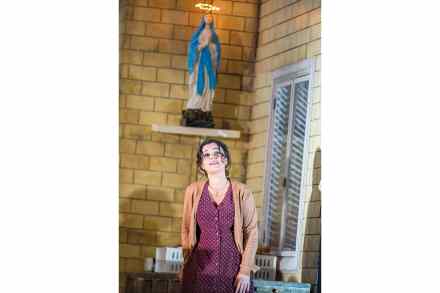

‘Here time becomes space,’ says Gurnemanz in Act One of Parsifal, and true enough, the end of the new Glyndebourne Parsifal is in its beginning. We don’t know that, at first: the sickbed image that’s glimpsed during the prelude doesn’t resolve itself until the opera’s closing scenes. In between, characters appear on stage in multiple forms, at different ages – past and future selves attendant on the present, whatever ‘present’ means in Monsalvat. Wagner, after all, makes it clear enough that time in the Grail Domain moves in mysterious ways, and his whole musical strategy reinforces that truth. So I can’t get too upset about those multiple personas, even though