A young American documentary film-maker recently said to me, ‘Do you want to know why no British documentary film-maker would ever make a film about something like the Diamond Jubilee celebrations? There was no blood! No violence! No crack babies! No tears! People were happy, and one thing British documentary film-makers hate is happy people and happy endings. If you want to get a doc made and shown in Britain, you gotta go for gloom and doom.’

Of course my American friend was exaggerating — but by how much? Think British documentary and what comes to mind? For me it’s Pete Postlethwaite wagging a finger and making apocalyptic warnings of ecological disaster in The Age of Stupid. Or it’s something terribly sad like Carol Morley’s Dreams of a Life, the story of a young black woman whose body was found in her council flat — three years after she had died. When it comes to the feel-bad doc, Britain leads the way.

But now there’s a growing number of dissenting voices within the documentary community who think it’s time that Brit-docs (and the documentary festivals that promote them) stop being so dour and depressing. Michael Stewart, festival organiser of the Open City Documentary Festival, is one of them. He told me, ‘In retrospect I realised how many gloomy documentaries we were showing — films about mass murderers, war criminals, cocaine gangs, sado-masochistic relationships, the tragedy of life among the down and outs.’

Hussain Currimbhoy denies that it’s all gloom and doom. He’s the man responsible for the selection of films at the Sheffield Documentary Festival. (This annual event is regarded by many in the documentary community as the Cannes of documentary film-making.) Currimbhoy concedes that Britain’s gloom reputation may have been true years ago but ‘anyone who says that now is just out of touch with reality’.

But just consider the topics of films shown a few weeks ago at the Sheffield festival in their ‘Best of British’ section. It presented a view of Britain as not only broken, but bloody and violent as well. There was a study of the violence within gypsy families (Gypsy Blood); and more violence in the story of deadly gang wars in Birmingham (One Mile Away). And there was violence and death with 7/7 One Day in London — a documentary about the terrorist bomb attack of July 2005 that killed 52 people. It was billed by the festival as having ‘intimate stories of agony, trauma and grief’.

Of course no British documentary festival would be complete without tales of global disaster, climate change and the horrors of deforestation. And for that Sheffield offered Aluna featuring the Kogi tribe of Sierra Nevada, Colombia, with their message that ‘we are destroying the earth’.

Could it be that there’s an ingrained bias against British documentaries that are too upbeat or soft? When it comes to getting your film funded there certainly is. Documentary film producer Simon Chinn (Man on Wire) told the audience at the Sheffield Documentary Festival, ‘Unfortunately, there are many more sources for those people who want their documentaries to change the world than those who want to tell good stories.’

One person who knows this first hand is journalist turned documentary film-maker Kate Spicer. She along with her film-maker brother Will made Mission to Lars, the story of her attempt to get her brother Tom, who suffers from a form of autism, to travel across America and meet his hero Lars Ulrich, the drummer from the heavy metal group Metallica.

It’s a very moving, upbeat film and has been praised by critics — but it was rejected for a screening at this year’s Sheffield Documentary Festival and the London Film Festival. Kate has never been given an explanation as to why but she has her suspicions. ‘I guess it doesn’t fit the idea of what a proper, serious documentary should be. Maybe my film is just too happy.’

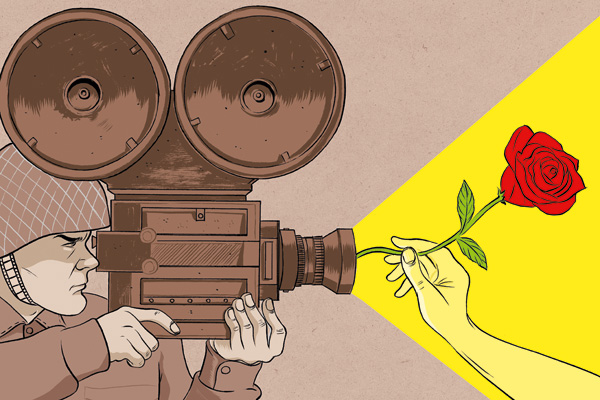

The roots of this bias go back to the early days of the British documentary movement. The term documentary was first used by film-maker John Grierson, director of Night Mail, in a 1926 film review. The progressive-minded Grierson saw documentaries as a medium for educating the masses and spurring them on to social reform. Documentaries became a part of the public-service ethos of British broadcasting and were serious, didactic and enlightening — but they were never enjoyed or watched by the masses they were supposed to appeal to.

Despite the cuts in funding from British broadcasting in the 1980s, the gloomy Brit-doc has survived. Today they are funded by NGOs and campaigning groups which have specific social and political agendas that deal with poverty or environmental issues, usually from a leftist/progressive perspective. A classic example of this was the 2009 feature film The End of the Line, a Brit-doc aiming to expose the ‘devastating effect of over fishing on the oceans’, that was funded by Waitrose and a whole group of foundations and charities in the UK and the US.

But there are signs that the boom in gloom is coming to an end. Since the critical and commercial success of documentaries such as Man on Wire (2008) and last year’s big hit Senna, there has been a move away from agit-prop docs to simple storytelling. The positive effect can be seen in the fact that more documentaries are gaining theatrical release and doing better at the box office (in 2011 British documentaries took £5.8 million, compared with £800,000 in 2010) than ever before.

Even the festival scene is begging to change. This year Michael Stewart decided his Open City Festival would break with the bleak past. ‘We’ve made a real effort to find feel-good movies, films that lift your heart and give you strength to see the next day, week, the next crisis, through. We’ve made a place for all those people who can’t face yet more misery and doom!’

And documentary film-makers are seeing this change at first hand. Pip Clothier is an award-winning documentary film-maker who tells me that not long ago commissioning editors wanted documentaries that were ‘edgy, redemptive tales featuring people in peril’. He recently pitched a film idea like that to a prominent television commissioning editor only to be told, ‘Sorry, too dark — we don’t do dark and gloomy any more.’

Of course, nobody wants documentaries to be all sweetness and light. We get enough feel-good films from Hollywood. But the hectoring save-the-world, feel-bad documentary is no alternative either. As Nick Fraser, editor of BBC’s Storyville, told me, ‘We need documentaries free from ideology and social utility; films that illuminate our world and ourselves with wit and imagination.’

Comments