Paul Nash: The Elements

Dulwich Picture Gallery, until 9 May

Paul Nash (1889–1946) is one of those rare artists whose work manages to be British, Modernist and popular at the same time without imploding. It is thus curious that there are not more exhibitions of his beautiful and poignant work. The last general Nash survey in London was at the Tate in 1975. More recently, the Imperial War Museum has shown his war work, and in 2003 there was a good and wide-ranging show at Tate Liverpool. With that exhibition the Tate no doubt felt it had done its duty to Nash, so the current, long-overdue London display was left to other hands. All praise, then, to Dulwich Picture Gallery for rising to the challenge. But a show of Paul Nash there presents certain problems. On the day I visited, the galleries were packed and there was a queue for admission. This is good for Dulwich but not so good for Nash. Its temporary exhibition space was not built for large crowds, and the work was too often invisible behind the massed backs of visitors, while the small rooms reverberated with unconsidered opinions.

‘A certain English timidity’ was one view I heard trumpeted by the female of the species, aptly demonstrating the danger of attending an exhibition burdened by preconceptions. I was sorry that an apparently intelligent visitor was unable to experience and savour the rare magic that Paul Nash offers to those who haven’t closed their minds. Mine must have been tuned to the right wavelength, for as I walked down from the station to the gallery I encountered a violently cropped tree, shelved around with fungi and hung with a single tendril of creeper. It looked wonderfully out of place in tidy Dulwich Village. I seemed already in Nash country.

The Dulwich show has been ably curated by David Fraser Jenkins, who has arranged the work according to theme rather than chronologically. This works well with Nash, and substantiates Fraser Jenkins’s interpretation rather than looking like a group of pictures constrained to illustrate an idea, as is so often the case nowadays. Subtitled ‘The Elements’, the exhibition focuses on the traditional quartet of earth, air, fire and water, and how Nash elucidated them. The centrepiece of the first room is a masterpiece from the first world war, entitled ‘We Are Making a New World’ (1918), depicting the shattered landscape of the trenches, a landscape reduced to its basic components. The experience of fighting in that war left an indelible mark on Nash, and it’s appropriate to register that at the start of the exhibition, under the sub-theme of ‘The Elements in Conflict’.

Here are beautiful early works such as the little-known ‘Falling Stars’ and the key image ‘Pyramids in the Sea’. I was intrigued by ‘Empty Room’ (1935) in which landscape meets domicile, and interior walls modulate into cliffs with all the logic of the subconscious. Also in this first room is one of my favourite Nash oils: ‘Landscape from a Dream’ (1936–8), a mysterious painting dating from his surrealist phase, when the earlier influences of Blake, Samuel Palmer and Rossetti had been assimilated and Nash was entering more fully into the realm of his own imagination. Opposite is the late painting, ‘Solstice of the Sunflower’ (1945), in which a great flaming seed-head bounds over the Downs, a toothed disc from a mechanised reaper, harbinger of death and a kind of fulfilment.

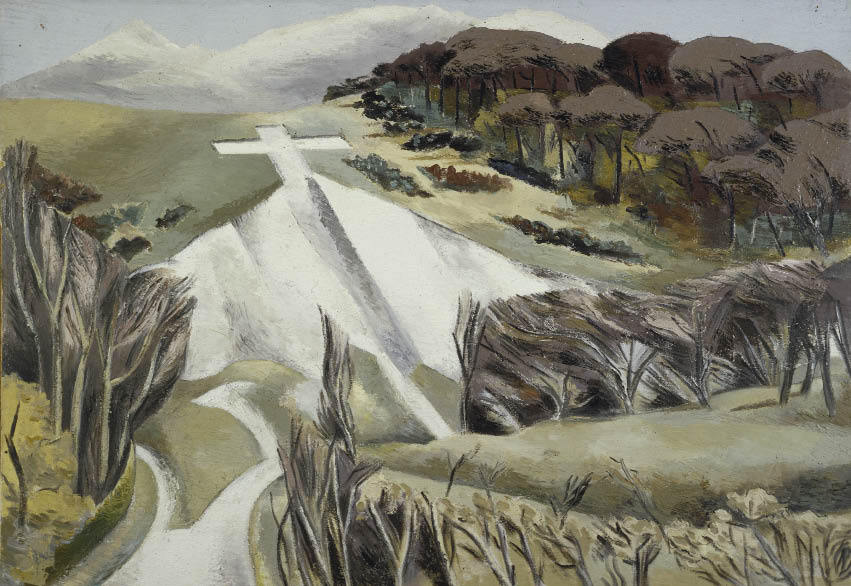

The theme of the second room is ‘A Path through the Elements’ and here are featured some of the lyrical and visionary landscapes for which Nash is rightly celebrated. Landscape is not drawn topographically, from the outside, but from within, as the artist identifies with his surroundings and translates them into lasting metaphors. So we have here the Dymchurch pictures, including the unfamiliar ‘Wall against the Sea’ and ‘The End of the Steps’ (both 1922), and such early delights as ‘The Wanderer’ and ‘The Orchard’. In the third room, titled ‘Elements as Refuge’, Nash’s tendency towards geometric distillation reaches its theatrical peak in ‘Landscape at Iden’ (1929), but is balanced by the exquisite and unaffected poetry of ‘Wittenham Clumps’ (1911–13), ‘Landscape at Pen Pits’ (1937), and a selection of Nash photographs and collages.

The final room, ‘Elements in Harmony’, is a triumph, with the early masterpiece ‘Chestnut Waters’ brought over from Canada and matched with ‘Winter Sea’, ‘Totes Meer’ and the marvellous ‘Landscape of the Vernal Equinox’. I felt thoroughly uplifted. David Fraser Jenkins is to be congratulated for this show, for a catalogue essay of refreshing directness and clarity, and particularly for seeking out lesser-known pictures by Nash in private collections. Just be prepared to queue.

At the Whitechapel Gallery is a free display of works from the British Council collection selected by Paula Rego (until 12 March), which contains a beguilingly delicate Paul Nash, ‘The Soul Visiting the Mansions of the Dead’, related directly to one of the watercolours at Dulwich. Around it is an exceptionally enjoyable group of paintings, drawings and prints, with some real surprises, such as a terrific early painting by Colin Hayes called ‘The Fifth of November’. Drawing, as one would expect in a Rego choice, is paramount. Look at the lovely Stanley Spencer ink design called ‘The Month of December: Gathering Holly’. John Craxton’s portrait of a Greek shepherd (illustrated in last week’s Spectator) is a marvel of precise and sensitive evocation. A group of three Sickert ink drawings with the famous ‘Ennui’ etching is balanced by a group of Graham Sutherland gouaches on another wall. There are fine things by Leon Kossoff, Mike Andrews and Frank Auerbach, two good Burras, a Wyndham Lewis watercolour figure, Vic Willing pastels, a 1944 painting by the criminally underrated Albert Richards, a surprising coil of rope by Prunella Clough and much more. This exhibition will tour in an expanded version to the newly opened Paula Rego Museum in Cascais, Portugal. Apart from being an unusual and stimulating selection from a little-known public collection, it is fascinating for the light it sheds on Rego’s own work.

Comments

Comment section temporarily unavailable for maintenance.