Despite occasional evidence to the contrary, I have persisted in the belief that the ability to play chess well indicates a powerful intelligence. Goethe wrote that chess was a touchstone of the intellect, while Pascal called it the gymnasium of the mind. Arthur Koestler romanticised the mental power of chess devotees, writing: ‘When a chess player looks at the board, he does not see a static mosaic, a “still life”, but a magnetic field of forces, charged with energy — as Faraday saw the stresses surrounding magnets and currents as curves in space; or as Van Gogh saw vortices in the skies of Provence.’

Conversely, anyone with a strong intellect should be able to rapidly grasp the essentials of chess. It has been my pleasure in recent weeks to observe the particular mental skills of Sharon Daniel, winner of the Channel 4 ‘Young Genius of the Year’ award. She is a Mensa member, has a stratospheric personal IQ and a line of chess trophies on her shelf at home. She is also an alumna from the 50,000 annual entrants to the Delancey UK Schools Chess Challenge, organised by the dynamic duo of Michael Basman and Sainbayaar Tserendorj. During the Genius shows, Sharon was at pains to emphasise how much chess had improved her IQ, as well as her powers of memory, focus, logic and analysis.

The young Paul Morphy was a precocious intellect of yesteryear. Aged 12, he used chess as the focus for his prodigious mental faculties and phenomenal gift of recall. Here is a game which he won against his father in coruscating style while he was not yet in his teens.

Paul Morphy-Judge Alonzo Morphy: New Orleans 1849; Evans Gambit

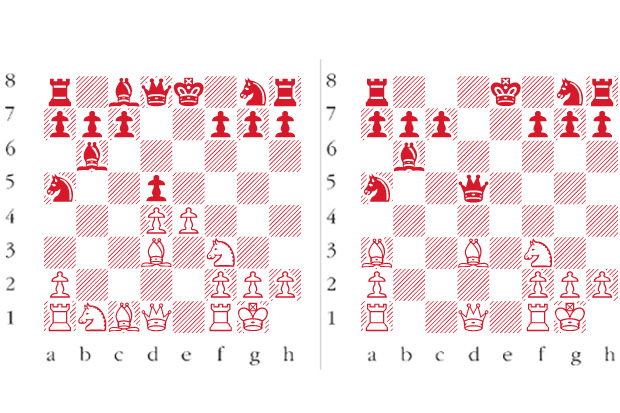

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 White’s next move introduces the infamous Evans Gambit, which has entranced aggressive players from Morphy to Kasparov. 4 b4 Bxb4 5 c3 Bc5 6 d4 exd4 7 cxd4 Bb6 8 0-0 Na5 9 Bd3 d5 (see diagram 1) Opening up the centre, while still undeveloped, is precisely what Black should not do. 10 exd5 Qxd5 11 Ba3 Be6 12 Nc3 Qd7 The punishment is condign. 13 d5 Bxd5 14 Nxd5 Qxd5 (see diagram 2) 15 Bb5+ A brilliant coup which exposes all of the defects in Black’s camp. 15 … Qxb5 16 Re1+ Ne7 17 Rb1 Qa6 18 Rxe7+ Kf8 19 Qd5 Qc4 20 Rxf7+ Kg8 21 Rf8 checkmate On board patricide. Morphy concludes this sparkling little gem of a game with a dazzling double discovered checkmate.

This week’s puzzle is a win by the best ever female player, Judith Polgar, who has announced her retirement aged 38.

Raymond Keene

Gifted and talented

issue 06 September 2014

Comments