Studies of Christianity’s problems and prospects often entail a distinction between the singer and the song. At an institutional level, the world’s largest faith is in deep trouble throughout much of western Europe – and increasingly in North America, too. Widely rehearsed elsewhere, the reasons for this steep decline include the spread of individualism along with an allied flouting of deference, mistrust of agencies said to lie beyond the tangible, and self-inflicted wounds such as the abuse crisis.

Yet many who mourn the spread of secularisation remind us that for all its flaws, the Church has a good story to tell overall. How so? Two answers stand out. First, Christian outreach still forms the largest single source of social capital on Earth. Second, when properly framed, the gospel message is both more reasonable and more inclusive than imagined either by sceptics or some stiff-necked believers. It supplies the richest available underpinning for values, including the sanctity of life, the dignity of the individual and human stewardship of the environment. Preachers can thus insist that we are not just animals wired up to the struggle for survival. Meaning, mattering and the quest for transcendence – a higher dimension of reality embodying more exalted values – are not illusions. Side by side with this awareness stands the belief that Jesus of Nazareth’s life was a self-revelatory act of God. Though the claim is disputed on many grounds, its foundations remain robust.

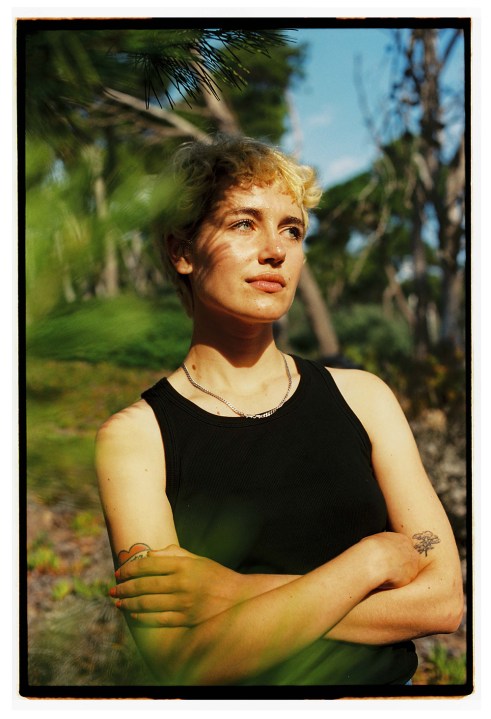

Why rehearse all this? Because the merits of Lamorna Ash’s book do not include the ground-clearing needed to establish co-ordinates for her very ambitious project. Don’t Forget We’re Here Forever certainly has an engaging premise. Inspired by the example of two Oxford friends who embraced Christianity seriously enough to consider ordination (and describing herself as depressed and disorientated), Ash embarked on a road trip around Britain that would also be a voyage of spiritual self-discovery. (For the record, she and I had a brief conversation over a cup of coffee while her researches unfolded.) Her text blends sketches of encounters at churches, retreat centres and other venues with large dollops of self-analysis. In an idiosyncratic mixture of memoir, reportage and one-sided advocacy, these elements don’t always combine well.

The book’s subtitle misleads on two counts. It is much more about Ash herself and her relatively small pool of interviewees than her generation as such; and the focus is on Christianity alone. There is value in concentrating on one creed – that of Ash’s own family, and part of the furniture when she was growing up – rather than many. But despite her background and obvious intelligence, the author isn’t very well informed about her subject matter. Small but telling mistakes, including ‘Easter Friday’ for Good Friday, are shadowed by conceptual cloudiness at a deeper level.

An advantage of defining Christianity in outline before testing its credibility is that space needn’t be wasted later on dispelling caricatures and canards. Atheists who announce they don’t believe in an angry ‘sky-god’ (Richard Dawkins’s term) invite believers to reply that they, too, are sceptics with respect to straw-man models of the divine. Likewise, the humanist who says you don’t need to believe in God to lead a good life can be reminded of the principle that grace operates well beyond the visible Church.

Another area benefiting from upstream discussion is sexuality. Ash devotes much space to interviewing gay Christians seared by homophobia in their congregations, but neglects the crucial matter of whether there are solid theological grounds for revising traditional attitudes. The answer is a resounding ‘yes’. The Bible condemns corrupt forms of same-sex desire, but does not reckon with stable, monogamous partnerships. Church teaching can therefore be revised in accordance with scripture’s underlying message about the link between sex and loving commitment rather than in defiance of it. That insight has been circulating for decades: priests and pastors don’t need to steal the clothes of secular campaigners before opening up to previously marginalised groups.

Viewed in the round, Don’t Forget We’re Here Forever is unbalanced by a heavy emphasis on identity politics. While zealous about what the Church needs to learn from the secular left, Ash seems oblivious of what secularism might learn from Christianity. Autonomy is not necessarily the apex virtue that she supposes it to be. And ‘a new generation’s search for religion’ should have told us more about the paths of the non-aligned, of others gravitating to the excluded middle and of conservatives. What about the many thousands of young people who flock to hear Jordan Peterson’s expositions of scripture, for example?

After a valuable experience at St Beuno’s, the Jesuit retreat centre in North Wales where Gerard Manley Hopkins studied in the 1870s, Ash finds a possible long-term spiritual home at a liberal Anglican church in London. These later stages of her journey are charted with insight and lyricism. The tale will be judged relatable by some. Others, though, will wish that she had allowed her ingredients to marinate for longer.

Comments