Another inquiry into child sexual abuse, another minister insisting that this time it will be different. Yvette Cooper promises arrests, reviews, a new statutory commission and the largest ever national operation against grooming gangs. But for the victims there is only one question that matters: what will this new inquiry do that the last one didn’t?

The last one, of course, was IICSA: the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse, led by Professor Alexis Jay. It took seven years, £180 million and 15 separate investigations to complete. And yet for survivors and campaigners, the abiding feeling at the end of it all was futility. IICSA had all the grandeur of a public reckoning but little of the justice. It was supposed to examine how institutions failed victims. Instead, it often resembled a procedural exercise: detailed, solemn, but ultimately toothless.

Bureaucratic musical chairs is what the British state does when confronted with a horror it would rather avoid

Grooming gangs – the most politically explosive scandal of all – were only one part of the report, and not even the most central part. It’s worth remembering what IICSA didn’t do. It didn’t summon senior officials under oath from the councils and police forces most complicit in cover-ups. It didn’t re-open the Rotherham files or interrogate why officers in Rochdale turned a blind eye. It didn’t assign blame. No one was sacked or prosecuted. And the abuse of white working-class girls by Pakistani men has continued.

What went wrong? In part, the answer lies in IICSA’s vastness. It was tasked with investigating abuse ‘in any institution’. It tried to do everything, and so did very little. Dame Lowell Goddard, its first substantive chair, resigned after a year, amid press reports alleging she had in private connected paedophilia in Britain to the prevalence of ‘Asian men’. Although she denied this, some commentators suggested she was pushed out of her position because she was willing to pursue the racial aspect of the scandal too vigorously for the Establishment’s taste.

When Professor Jay took over, the inquiry quickly became a compromise. Less testimony under oath, more closed sessions. More ‘survivor forums’ in place of public hearings. The kind of scrutiny that might have terrified local councillors or police officers – some of whom we now know were complicit – never materialised. Jay was praised for her 2014 report into Rotherham, but under her leadership IICSA avoided detailed scrutiny of grooming gangs and limited the use of public hearings or sworn testimony. Instead we got another nod to ‘institutional failure’, another recommendation for a new ‘Minister for Children’. It was bureaucratic musical chairs, the default response of the British state when it is confronted with a horror it would rather avoid.

Then, in January, Baroness Casey, a former Victims’ Commissioner, was commissioned by the Home Secretary to carry out a rapid national audit into grooming gangs. Her findings included a recommendation to hold a full national inquiry, which was duly announced by Cooper on Monday. Her report did what IICSA refused to: it focused on the racial dimension and acknowledged institutional evasion. Casey confirms that Pakistani men are disproportionately represented among grooming gang offenders, and that many local agencies avoided confronting the issue for fear of being called racist.

For all the praise her audit has earned, it still falls short. It is full of faddish red herrings about the ‘adultification’ of adolescent girls. Did the perpetrators target pubescent white girls because they were subconsciously ‘adultifying’ them? Of course not. This drivel is harmful, as it reframes a specific problem – British Pakistani men targeting vulnerable white girls – into a wider critique of society and its attitude towards adolescent girls, for which we are all allegedly culpable.

One part of the review, quoted by Cooper in her speech, featured a line from a police officer who stated that ‘If Rotherham were to happen again today it would start online’. This statement not only implies that Rotherham was a one-off historic incident; it again recasts the issue of racialised grooming into a Luddite whinge about the online world. The fact that the police would prefer the focus of the inquiry to be on the internet, which they can access from the safety of their offices – rather than the real world in which racialised grooming happens – is unsurprising.

What should this new national review aim to do? First, it must treat the scandal as an ongoing national emergency. As recently as January, eight Pakistani men in Keighley were sentenced for the sexual abuse of girls as young as 13. Some survivors believe the problem is worse today than it’s ever been. Cooper has announced that more than 1,000 closed cases are being reopened. But the new inquiry must map the networks in the same way that the Metropolitan police’s old Gangs Violence Matrix did, before it was shut down in 2022 over accusations of racism.

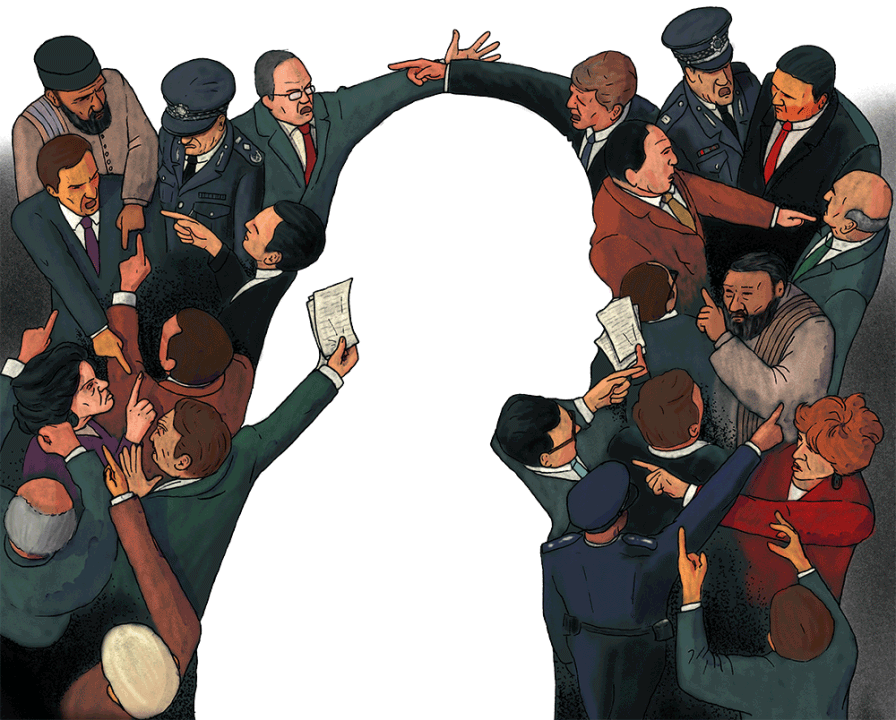

Second, this inquiry must make full use of its statutory powers. IICSA excluded Rotherham, Rochdale and Oxford from thereport on the grounds that ‘independent investigations’ had already taken place. The result was an evasion of accountability. Key individuals were never questioned. Blame was dispersed into a haze of lessons and reviews. This time, there can be no excuses. If police chiefs ignored abuse warnings, they must be named. If senior council officers buried reports to avoid accusations of racism, they should explain themselves. Justice demands that individuals, not just systems, are held to account. We must make an example out of those who prioritised their own comfortable lives over preventing the abuse of children.

Third, it must ask the difficult questions that IICSA and others wouldn’t. Was religious doctrine used to justify this abuse? Were vulnerable white girls seen as ‘fair game’ because they were not Muslim? Did authorities look the other way because they feared that to intervene would be to inflame racial or religious sensitivities? How far were the police complicit? Did Pakistani gangs intimidate witnesses and social workers? These are not conspiratorial talking points – they are evidenced in transcripts from trials and elsewhere. An inquiry must drag these questions into the light without bogus, cowardly equivocation around ‘Islamophobia’.

Success in this review will not look like victim panels and ‘enhanced data-sharing’. Instead, it will look like accountability in parts of the country which we know to be afflicted by racialised rape gangs. Take Bradford. It has never had a full public inquiry, yet its story is one of the most shocking. Fiona Goddard, a survivor, says she was raped by more than 50 men while living in a council–run children’s home. David Greenwood, the solicitor who played a key role in exposing Rotherham, believes Bradford could be worse still. Based on safeguarding statistics, he estimates up to 72,000 children may have been at risk of exploitation there since 1996. That figure seems implausible until you learn that in just eight months, 2,500 children were classed as ‘at risk’ by local authorities.

Yet Bradford’s institutions resist scrutiny. Susan Hinchcliffe, Bradford Council’s leader, refused to commission a local inquiry in October 2021, and Tracy Brabin, the West Yorkshire mayor, refused similar calls on the grounds of limited local resources which would be better spent protecting women and girls today instead of investigating ‘the past’.

Here is the test: this new national inquiry must force a reckoning in Bradford. If it confines itself to the usual places and people, the usual bland conclusions, it will have failed. Bradford doesn’t need community cohesion statements or survivor focus groups. It needs summonses. It needs officials under oath. It needs the truth. Anything less will just be a repeat of IICSA and its shortcomings.

Comments