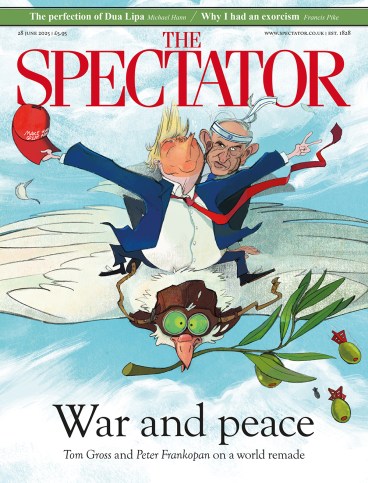

These legendary lives need the clutter cleared away from them occasionally. Lawrence Durrell and his brother Gerald turned their family’s prewar escape to an untouched Corfu into a myth that supplied millions of fantasies. It still bore retelling and extravagant expansion recently, if the success of ITV’s series The Durrells is any sign. (One indication of that pleasant teatime diversion’s accuracy: the actor playing Larry, Josh O’Connor, is 6ft 2in. Larry himself was a whole foot shorter.) How Louisa Durrell, struggling with life in Britain after returning from India, went in a bundle with her children to a Greek island of cheap Venetian mansions, heat and innocent adventure is always going to have its appeal.

What the Corfu idyll leaves out is why we should be interested in the story in the first place. Lawrence Durrell was a very good novelist, and this episode was only one of many that contributed to his work. That probably needs saying, since he is out of fashion today for a number of reasons. One is that his books, full of extravagant evocations of exotic places and pleasures, no doubt appealed to a British readership in the 1950s that was starved of such things. But how do the delights of Corfu, or indeed Alexandria, stand up when any of us can hop on a plane and sample them for ourselves?

A second reason is connected: Durrell’s literary style is undoubtedly baroque, his concept of a novel’s structure sometimes baffling (especially in the late Avignon Quintet) and in general open to accusations of over-indulgence. I read the Alexandria Quartet recently for the first time since I was at school, and was surprised by how well it had survived – a steely, bloodthirsty thriller of betrayal, deals and gun-running coagulating out of innocent romantic delusion. Individual episodes, such as the duck shoot in Justine, are wonderfully exciting; and the prose, which I had expected to find overblown, can be startlingly close to the Martin Amis of the 1980s:

Melissa’s dressing-room was an evil-smelling cubicle full of the coiled pipes that emptied the lavatories. She had a single poignant strip of cracked mirror and a little shelf, dressed with the kind of white paper upon which wedding cakes are built. Here she always set out the jumble of powders and crayons which she misused so fearfully.

A further reason for Durrell’s unfashionableness is, of course, precisely the biographical expansion, and not just the Corfu fantasy. Sappho, his daughter from his second marriage, set down in her diary details of her sexual abuse by him before committing suicide, just as his character Livia, based on Sappho, had been described as doing. These things can destroy a novelist’s reputation.

For the moment, his story is still worth telling, and although this is not the first or most important biography, it has a strong appeal – which is partly accidental. Michael Haag, who had already written books about Alexandria and the Corfu episode, was at work on a full biography when he died in 2020. This turned out to be complete up till the end of the war, with Durrell only just starting on what would be Justine. Profile Books has decided to publish it as it stands, which in fact is an alluring decision. What we have is that most interesting approach of literary biographies – the formative years before fame.

The heady society of wartime Egypt, and the sense of being at the centre of things, changed Larry fundamentally

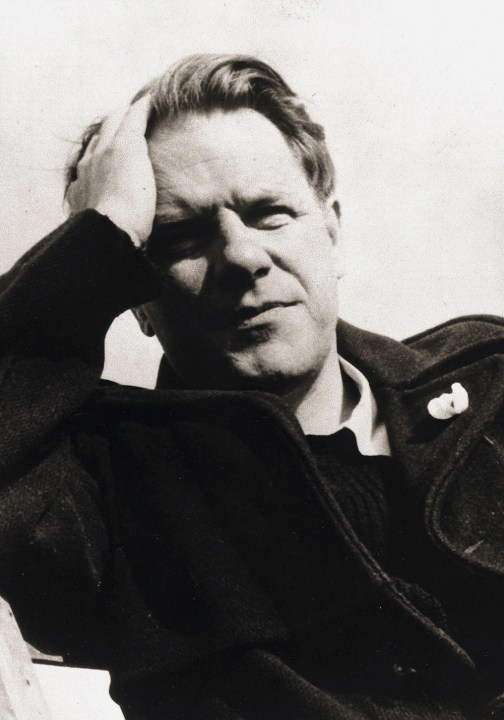

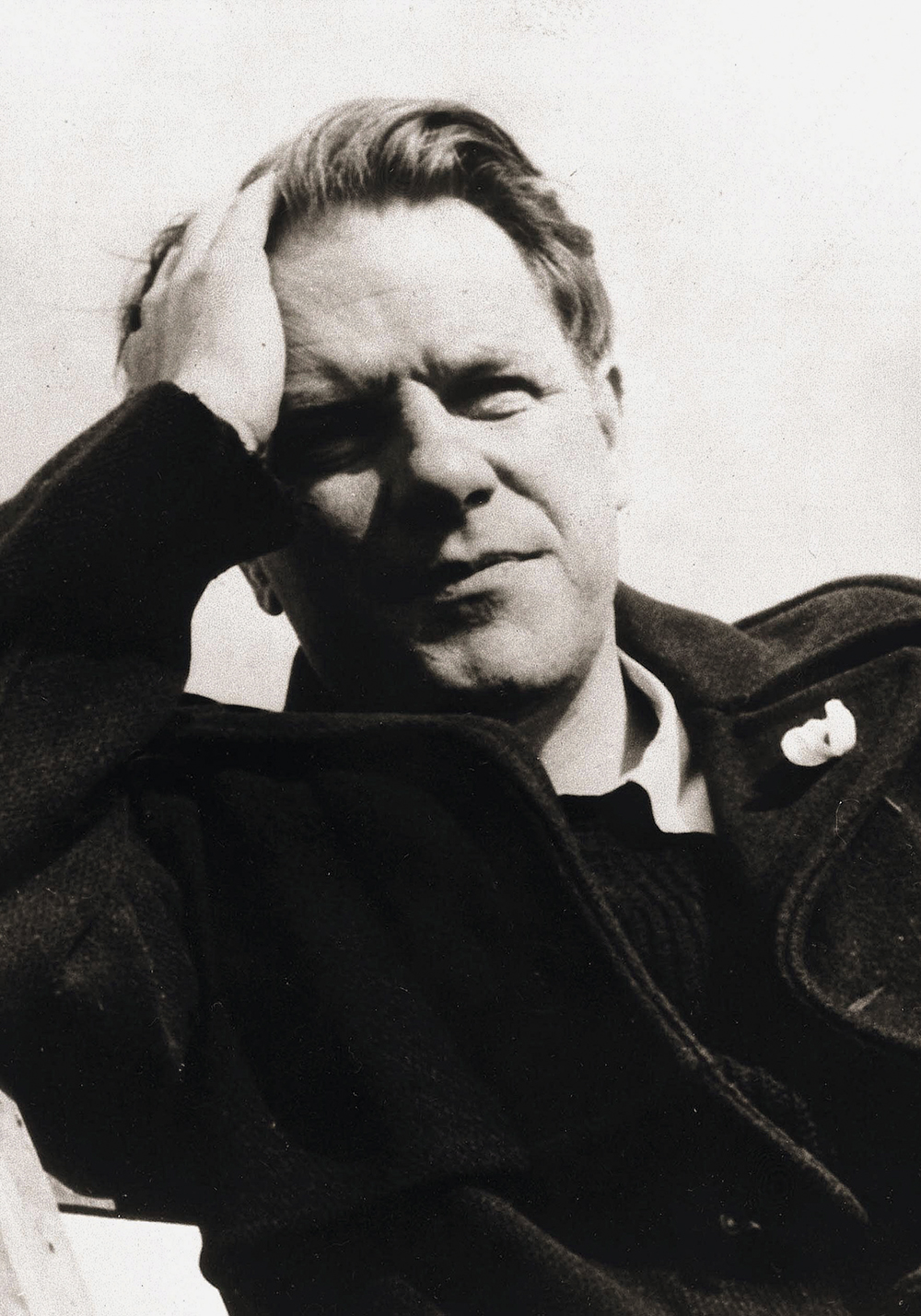

Durrell hardly ever lived in Britain, and indeed in later years the question sometimes arose of whether he was a British citizen at all. He was born in India in 1912, the son of a brilliant engineer (the wonderful loop at the top of the great Darjeeling railway is his father’s work). Some memories of Indian life must have fed into the grotesquery he was capable of as a novelist. When his sister was bitten by her pet spaniel, rabies terrors meant that they had to carry the dog’s severed head in a canister on a long train journey to be tested. The family was not quite Raj top-drawer, but Durrell was nevertheless sent back to school in England, and lived with his returning mother in a succession of inappropriately ostentatious houses.

Aged 19, he was told by her that he was too much for Bournemouth. ‘You can be as bohemian as you like, but not in the house. I think you had better go somewhere where it doesn’t show so much,’ she said. A brief and raucous Bloomsbury period followed; a noisy marriage; and then the celebrated decampment en masse to Corfu. It was not quite as idyllic in all respects as it has been painted. The young Durrells’ enthusiasm for nude sunbathing with each other and visiting friends of both sexes (startlingly documented here in photographs) was one thing the Corfiots jibbed at.

The decisive period, however, to which Haag devotes most space, was 1940s Egypt. At the outbreak of hostilities, Durrell had been evacuated with his wife Nancy and infant daughter Penelope Berengaria from Kalamata in the Peloponnese. The experience of war in Egypt was tumultuous, and the mix of different cultures, officialdom, idealists, high society and bohemian life is exactly what makes the Alexandria Quartet so enthralling. The Durrells’ marriage broke down and Nancy departed in 1942.It is hard not to conclude that the war, the heady experience of grand café society and the sense of being at the centre of things had changed Larry fundamentally. Soon he was in a tempestuous relationship with the unstable Eve, who became his second wife and ultimately the disturbing Melissa of the Quartet.

As captivating as this novel sequence is, it shows (as Haag frankly admits) that Durrell’s experiences did not quite equip him to write about the political situation. It has always been agreed that it would have been impossible for his character Nessim, a Copt, to have been a gun-runner for Zionists in Palestine. Durrell decided to make him one because he was irresistibly drawn to the idea that, alone in the drama, Nessim would have wanted to marry the Jewish Justine out of calculation rather than passion. Though it reveals the limits of what Durrell could accept about the time and place he lived in, the Quartet has its own reality. What he observed turns into a compelling statement, made of smoke and steel. It ought to return to fashion in time.

Haag’s book is highly readable and elegantly put together, and, if unintentionally, produces a satisfying whole by stopping where it does. In fact, I suspect that the second half of Durrell’s life, especially the late years – full of tragedy, bad conduct and an undeniable decline in talent and readability – would not be as enjoyable an experience. We end with him returning to his beloved Greece after the war and starting to work on Justine, a book which hit the British reading public in 1957 at exactly the right moment.

A full biography, on the other hand, would have to include Sappho’s suicide; the dismal and incomprehensible final volumes of the Avignon Quintet (the last of which Faber returned to be revised, so little impressed were they); and Durrell’s death in 1990, before the French state could seize his property for non-payment of taxes. I met him briefly in London in 1983; the strange thing now is that I have absolutely no impression of his being as short as he actually was. His presence was immense.

Though this is a good biography, I have a request of publishers in general. Lawrence Durrell has been done often, and very respectably. In the course of Haag’s descriptions of life at the British Embassy and British Council in wartime Egypt, the name of Robert Liddell comes up. Liddell was also a seriously good novelist, and one who often appears as the adviser and friend of writers such as Barbara Pym, Elizabeth Taylor and Ivy Compton-Burnett. His story – he was abused as a child, abandoned England after the death of his beloved brother, and lived in Egypt and Greece – could be gripping. Might a publisher, for once, commission not a life we’ve heard several times but one of this remarkable but still strangely neglected novelist?

Comments