Only last week, I was having lunch when The Salt Path came up in conversation. ‘That’s the one about the woman with the terminally ill husband who went off round Cornwall, wasn’t it?’ said one friend. I responded, perhaps a little heartlessly: ‘Yeah, and then the husband weirdly failed to die and she got a couple of sequels out of it.’

There’s nothing we Brits love more than a story about an underdog battling adversity and the inextinguishable resilience of the human spirit

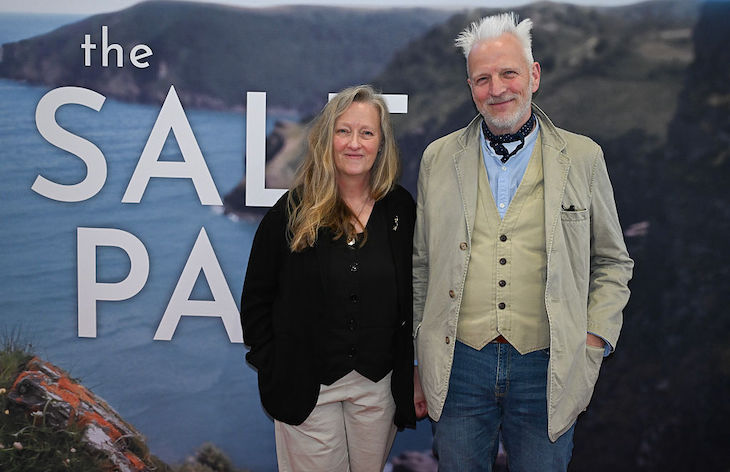

The twinge of self-reproach I felt then has evaporated. The Observer yesterday carried a report into the background of that book’s author, Raynor Winn, and her husband Moth (real names Sally and Tim Walker), and discovered that many details in her memoir were, to put it delicately, not quite as she claimed.

The inciting incident for The Salt Path was the couple finding themselves homeless and destitute after their ‘forever home’ was taken from them, Wynn wrote, when they invested in a friend’s company which failed – and that faithless friend somehow won a court case assigning their house to him.

The Observer’s reporter Chloe Hadjimatheou, however, discovered evidence that the real reason the Walkers lost their house is that while working as a book-keeper Sally had defrauded the small company she worked for out of £64,000; and that the house became collateral on a loan she took out to reimburse her victims in order to prevent criminal charges being preferred against her. And it appears that even while – according to The Salt Path – the couple were left after the loss of their house with no option but to wild camp in the UK, they owned a property in rural France.

Since then public records have shown five county court judgments against the Walkers between 2011 and 2014, at least one of which came four years before the publication of that bestselling book. A local garage owner who says they still owe him nearly £800 asked the paper’s reporter plaintively: ‘If you see them, can you tell them to pay me? I think they can afford it now.’

As for Tim Walker’s ‘miraculous’ recovery from the degenerative brain disease his wife claimed he had – corticobasal degeneration, or CBD, a particularly savage neurological affliction in the same family as Parkinson’s – the Observer spoke to no fewer than nine specialists in CBD and they are reported as being unanimously ‘sceptical about the length of time he has had it, his lack of acute symptoms and his apparent ability to reverse them’. One said simply that the story ‘does not pass the sniff test’.

Sally Walker has not commented on the specifics of the allegations against her – issuing instead a written statement through lawyers burbling about the ‘physical and spiritual journey Moth and I shared, an experience that transformed us completely and altered the course of our lives’. Her publishers, her literary agent and the producers of the new film based on the book all failed even to respond to requests for comment. For all we know at this stage there is a perfectly reasonable explanation for these apparent discrepancies. But I think we can say that the response from those involved, at least so far, is consistent on the face of it with ‘bang to rights’.

As will sometimes be said of the bestsellerdom of books like The Salt Path, there’s nothing we Brits love more than a story about an underdog battling adversity and the inextinguishable resilience of the human spirit. But there is, after all, one thing we Brits do love more. What we really love is discovering that a story about underdogs battling against adversity and the inextinguishable resilience of the human spirit has turned out to be a load of old cobblers. We eat that stuff up, as witness the rapturous social media response to the Observer’s scoop.

The big question, though, is: does it matter? After all, ‘literary nonfiction’ is all the rage these days. Everyone recognises that memoirs are unreliable. As long ago as the 1960s Norman Mailer, in Armies of the Night, was playing around with the distinction between ‘the novel as history’ and ‘history as a novel’. ‘Autofiction’ and ‘the nonfiction novel’ have places of honour in the classier branches of Waterstones.

More eminent writers than we have space to name here, no question, have been scoundrels or criminals. And many non-fictionists have been caught making things up. The late Ryszard Kapuscinski continues to enjoy an elevated reputation despite his history of wholesale fabrications. Johann Hari bounced back robustly from being caught inventing or plagiarising quotes. Doubt – to say the very least – has been cast on the truth of memoirs by Constance Briscoe, Binjamin Wilkomirski, James Frey, JT Leroy, Judith Kelly and countless others.

But I think it does matter. It’s not enough to equivocate about the ‘higher truth’ of the books in question, or the ravishing prose, or the – blech – ‘physical and spiritual journey’. ‘Nonfiction’ is a label that makes a particular claim on the public imagination. Believing ‘this actually happened’ is the reason that we buy very many more badly written celebrity memoirs than we do badly written celebrity novels. It’s why those syrupy stories of the triumph of the human spirit sell in scads – and why, perhaps, that genre seems to be particularly vulnerable to fabrication. It’s telling that one of the most notorious frauds in the genre, James Frey, tried and failed to sell his A Million Little Pieces as a novel before hitting the jackpot by packaging it as a memoir.

Unless Sally Walker is quick with a fully convincing explanation of why her books, marketed as ‘unflinchingly honest’, appear to be anything but, I think publishers and the reading public will be entitled to ask her to, well, take a hike.

Comments