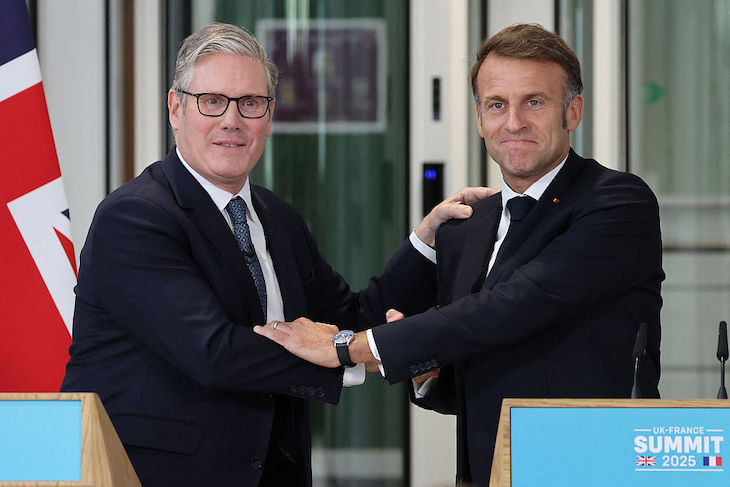

As French President Emmanuel Macron visited Britain this week for the first French state visit in over a decade, a deal on tackling small boat migrants became the trip’s centrepiece. Ahead of the visit, in an apparent sign of greater co-operation, French police were filmed wading into the water to slash the sides of an inflatable migrant boat with knives, preventing it from attempting to cross the English Channel. The relative ease with which they were able to do so proves that France could prevent many Channel crossings if they wanted to.

But the deal that has emerged is thin gruel. Other EU nations – including Spain, Italy, and Greece – have objected based on concerns that they might be obliged to take migrants returned to France. The EU Commission has also questioned whether the deal has strayed into areas of EU competency.

With nearly 200,000 people having crossed the Channel on small boats since 2018, the existing asylum system is clearly broken

A pilot scheme will be based on a ‘one-in, one-out’ policy but numbers will be small. Under the scheme, France will agree to accept back, within days or weeks, some illegal immigrants who have crossed the Channel. In return, Britain would accept an equivalent number of asylum seekers from France, with a focus on those with family already in Britain. The idea is that those seeking to cross the Channel will be dissuaded by their rapid return to France, putting them off further attempts, while the use of the regular asylum system would be encouraged. Yet, while a deterrent is necessary to stop the crossings, it is far from clear that the planned deal will be effective anyway.

The small boats crisis began in 2018, whilst the UK was still a member state of the EU, and by January 2019 the French and UK Governments issued their first joint ‘action plan’ proclaiming their determination to stop illegal crossings. When the UK complied with EU rules on asylum seeker transfers, for these purposes after Brexit and until the end of 2020, it applied the procedures within the ‘Dublin III Regulation’, a 2013 piece of EU legislation which decides which Member State should be responsible for an asylum seeker’s claim.

Transfers out of the UK numbered only in the hundreds. By the end of our participation in the Dublin process we were taking more asylum seekers than we were returning. Dublin III is simply not a very effective system, and transfers to Greece (the state of first illegal entry for a significant number of migrants) have been procedurally difficult for years due to European Court judgments.

Nonetheless, the Starmer and previous Conservative Governments, unwilling to countenance the radical change to domestic laws necessary to return asylum seekers en masse to their countries of origin, have been trying to negotiate a Dublin-style agreement at an EU or national level for years.

Replicating a Dublin-type process with France is a mere sticking plaster, likely looking to exchange mere hundreds when over a thousand migrants can and do cross the English Channel in one day. It would be just another footnote in the long story of politicians lacking the moral courage to reform our ineffective asylum and immigration system.

The litigation against the Rwanda scheme showed that third-country transfer agreements (i.e. not to their country of origin) face a high degree of legal jeopardy under our current framework. Dublin III worked (albeit not well) when we were an EU member state because EU law was supreme and overrode domestic law in a way that limited the routes of challenge for inventive human rights lawyers.

Under a new UK-France deal, however, British courts could legitimately review applicants’ ECHR and UN Refugee Convention claims to have their case considered in the UK on the grounds that France’s system lacks adequate safeguards or that they are at risk of onward removal from France to a country where they would face persecution. Such grounds of challenge are spurious at best, ridiculous at worst; but then again so are so many other successful attempts to avoid deportation.

We are well past the stage where tinkering either with international or domestic law will solve the sheer dysfunction of our immigration system, and the public recognise that too. A deal with the French that bakes in current unworkable international standards such as EU common asylum law, the ECHR, and the UN Refugee Convention will be a further rearranging of the proverbial deckchairs.

Much is written about Britain needing to repeal the Human Rights Act and leave the ECHR. But such reform, though a necessary first step, is still insufficient. As well as removing ECHR blockers to deportation, we also need to simplify our own Byzantine domestic immigration legislation, to curtail endless appeal and judicial review rights, and remove legal requirements to support asylum seekers which act as such a powerful pull factor to migrants in the first place.

This should not be seen as unthinkable. Our modern system of immigration appeals only dates back to the 1970s and prior appeal processes, like the Immigration Boards and the Deportation Advisory Committee, were abandoned when they failed to work. For much of the twentieth century there was no right to appeal the Home Office at all.

With nearly 200,000 people having crossed the Channel on small boats since 2018, the existing asylum system is clearly broken. There is an obvious link between those arriving and violent or sexual crimes, while the cost of looking after these arrivals runs into the billions. Rather than time-wasting attempts at a deal with France or other European nations based on trying to preserve existing legal frameworks, politicians need to have the moral courage to start anew and implement tougher solutions.

Comments