The UK’s worklessness problem is a well-documented crisis. Over six million people in the UK – almost a sixth of the working-age population – are on out-of-work benefits, a number that has nearly doubled in the last seven years. The government’s attempt to begin to address this with the Universal Credit and Personal Independence Payment Bill ended in fiasco. Diagnoses for the spectacular rise in worklessness vary from the long-term effects of the pandemic through to a lack of well-paid jobs to the perverse incentives within the welfare system. But one notable culprit seems to have escaped the attention of policy wonks: autism.

People with autism could therefore make up as much as a fifth of all out-of-work benefit claimants

There are between one and two million autistic people in the UK, over half of whom are undiagnosed. Some would suggest this figure is inflated: after all, in the mid-twentieth century, autism was thought to affect only 0.04 per cent of people. It has been caught up in broader concerns around overmedicalisation; a real phenomenon which is part of the reason behind the rise in the percentage of disability benefit claimants citing poor mental health as their primary condition. In 2002, poor mental health was the main condition for 25 per cent of claimants. This had risen to 44 per cent as of last year.

However, there are good reasons to think that there are over a million autists in our country. Many autistic individuals are never pushed towards diagnosis because they become increasingly adept at ‘masking’ – effectively, pretending not to be autistic in front of others. Autism diagnosis is still extremely difficult to access thanks to the state of NHS waiting lists. Autistic people seeking diagnosis in Oxfordshire, for example, currently have to wait up to 18 years before assessment. Most importantly, autism’s effects are very real: 70 per cent of autists – under the current diagnostic definition – are out of work. People with autism could therefore make up as much as a fifth of all out-of-work benefit claimants. Putting all of them into work would bring us back to a number of claimants we have last seen before the pandemic began.

While a full employment rate for autists is unrealistic, there is no reason why the majority should not be able to find productive, rewarding employment. Autism is currently diagnosed on a three-level scale; the higher the level, the more support the individual needs. Those on level one, and most of those on level two, are perfectly capable of full-time employment with the right adjustments. Lots of autistic people are well-educated, and they are generally better able to focus and are less subject to social pressures. I am friends with many, and they are some of the most productive and knowledgeable people I know. Indeed, in 2022 JPMorgan found that new employees hired through their ‘Autism at Work’ programme could be 140 per cent more productive than employees who had already been at the company for years.

Despite this, autistic university graduates are still over twice as likely to be out of work as non-autistic graduates. Unlocking this well of productivity does require some adjustments. HR hiring practices often discriminate against autistic people by judging them based on social cues that people with autism simply do not pick up on, or using deliberately roundabout language that autistic people are likely to interpret literally.

Being forced to work in loud, crowded or harshly lit spaces can also be extremely unpleasant for people with autism, to the degree of being impossible.

Above all, and speaking from personal experience, supposed support for autistic people can be very patronising. Much of the autism ‘community’ has been adopted by the radical left, keen to add ‘neurodiversity’ to its list of special interests, with disastrous effects for autistic people’s self-perception, as they are encouraged to wallow in self-pity rather than take responsibility for their life.

Well-intentioned attempts at taking the condition seriously end up overemphasising the inevitability of its drawbacks or coming up with entirely new problems that are not linked to autism at all. Worklessness is accepted as necessary self-care, when often the opposite is true – we know work to be a strong preventative factor where it comes to poor mental health. Masking, too, is often presented as unequivocally harmful. Although it can be depressing, especially without friends with whom you can ‘unmask,’ changing your behaviour at times to slightly better fit in with colleagues can, unsurprisingly, improve your life quality.

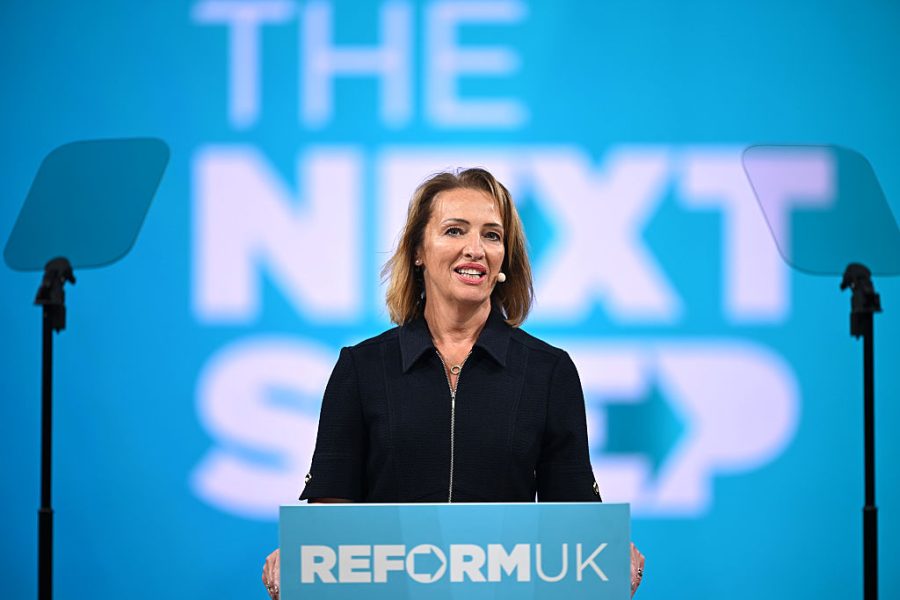

The previous Conservative government did demonstrate some interest in tackling the problem. Mel Stride, then the Secretary of State for Work and Pensions, commissioned Sir Robert Buckland to produce the Review of Autism Employment which was published in February of last year. The Review made some decent recommendations, but too many were too vague and too generic. The report itself notes that none of them require legislation, but serious change often does.

Out-of-work autistic people remain a huge opportunity cost. Their pent-up potential is vast – getting over a million people into work, many of whom are exceptionally productive, and three quarters of whom want to be employed. This leaves an opening for Keir Starmer’s government. Stuck between a patronising left and a right that too often denies that autism is a real condition, the problem has scarcely been noticed – let alone adequately addressed – by the higher-ups. It is too big to ignore now. If Starmer can make it go away, he would go a long way to solving Britain’s worklessness woes.

Comments