David Bowie wrote a musical. Well, nearly. A cache of notes found in his New York apartment after his death indicates that he was planning a new theatre project in the final months of his life. The archive includes the phrase ‘18th cent musical’ among a collection of Post-it stickers filled with ideas and motifs. Creating a musical would have satisfied a lifelong ambition. ‘Right at the very beginning,’ he told the BBC in 2002, ‘I really wanted to write for the theatre. I could have just written for theatre in my living room but I think the intent was to have a pretty big audience.’

He seems to have chosen Spectator as the show’s title. The word appears in capital letters on the cover of an exercise book containing his notes on the original Spectator which was published by Richard Steele and Joseph Addison between 1711 and 1712. The journal was a daily archive of news, gossip, political stories, reflections on social trends and so on. (The present magazine, founded in 1828, bears the same name.)

Bowie saw it as a fertile source of material, and he listed the characters and pseudonyms used in the original Spectator. ‘Other contributors,’ Bowie wrote, ‘Sir Roger de Coverley, the bully Dawson (infamous), an unnamed attorney, a merchant Sir Andrew Freeport, a soldier, Captain Sentry.’ His research method was rather schoolmasterly. After reading each Spectator article he wrote a brief summary of the story and gave it a score out of ten. He describes an essay by Addison as ‘an analogy of greed versus monarchy’ and awards it five marks. A contribution by Steele about the sensation of loneliness in the theatre does better. It gets six out of ten. Was he grading their literary quality? Possibly not. The numbers may reflect the utility of each essay as a source of inspiration.

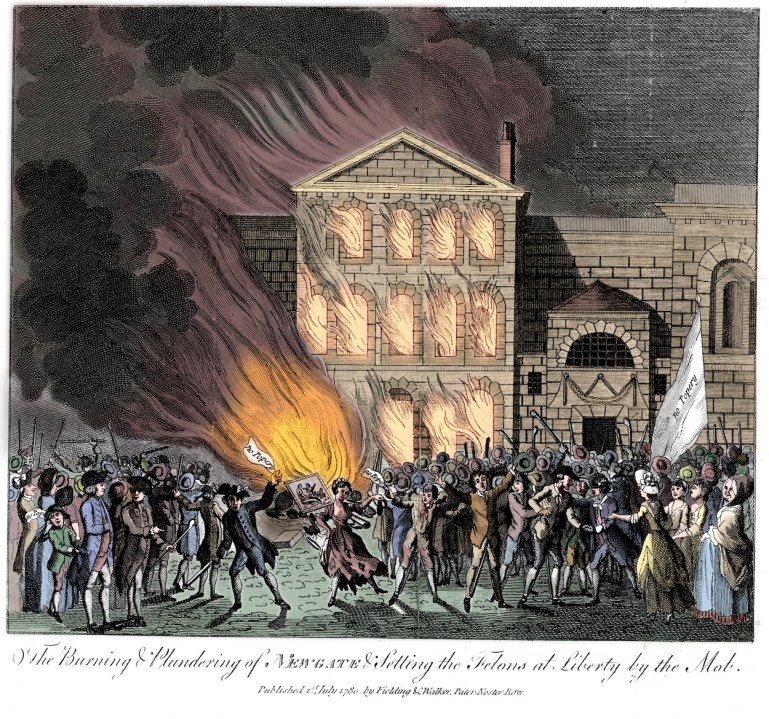

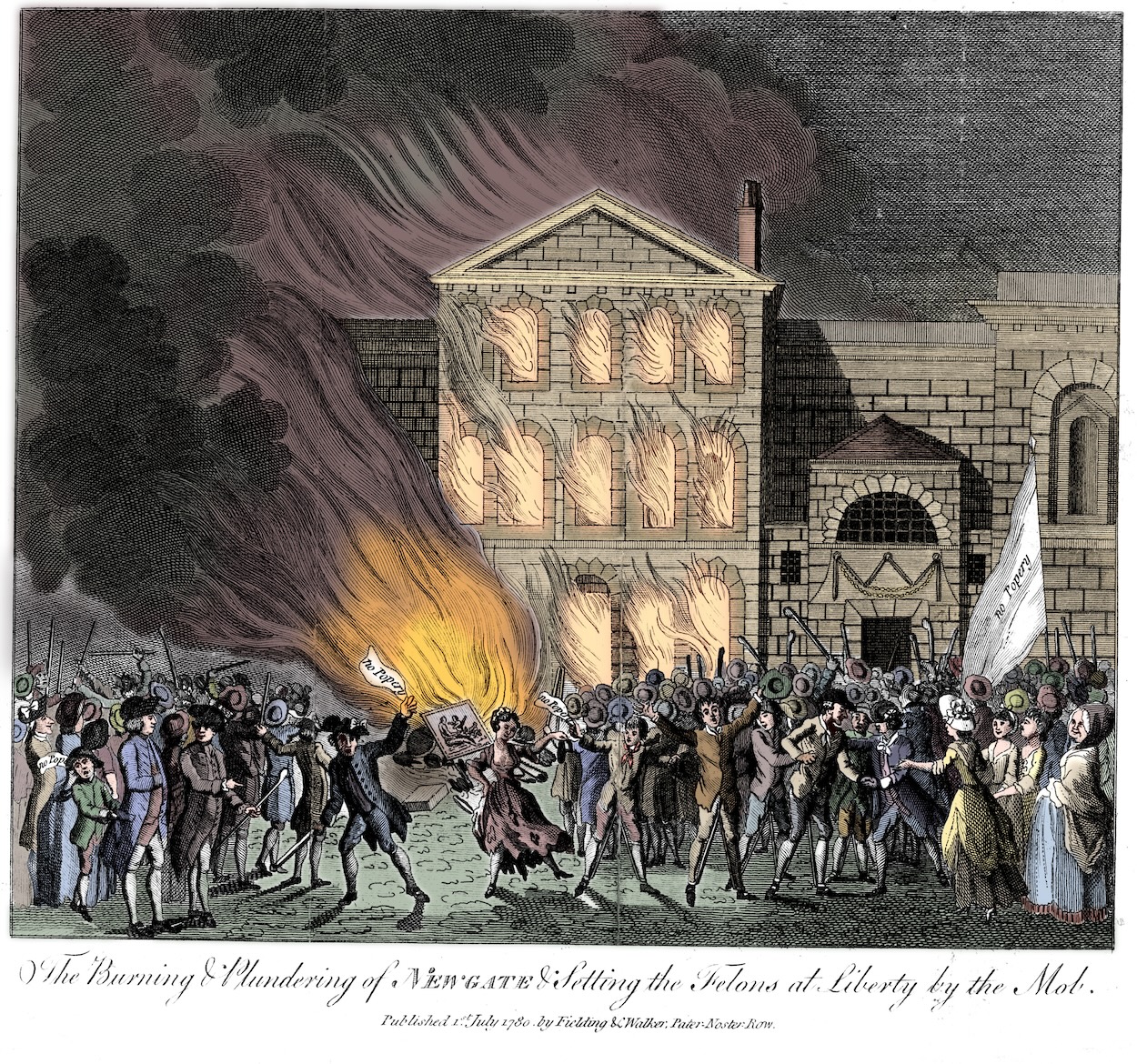

His research moved beyond the early 18th century. The Post-it notes contain landmark dates like the death of Alexander Pope in 1744, the publication of Johnson’s dictionary in 1755, and the formation of the Royal Academy in 1758. Thomas Gainsborough’s passing is marked in abbreviated form. ‘1788 Gainsb dead.’ Bowie’s memos suggest a creative mind searching for momentous events that might give shape to the narrative. ‘1750,’ he writes, ‘an earthquake 30 seconds everyone leaves for country.’ Another significant date is underlined. ‘1778 Cath: Relief Act.’ He adds, ‘1780, Gordon Riots.’

He seems fascinated by rebels, writers and painters, although he fails to mention William Blake. ‘1714,’ he writes, ‘Hogarth apprenticed to Ellis.’ This refers to the engraver, Ellis Gamble, whose workshop was located in Leicester Fields, near the present-day Leicester Square. Some of the information seems trivial but Bowie is probably looking for friendships and commercial alliances to serve as building blocks for his story. ‘April 1741 Reynolds writes to friend of Hogarth from home.’ That looks flimsy but to a dramatist it could be the cornerstone of a play.

Some of Bowie’s jottings are more basic and refer to locations like ‘Hogarth’s Studio’ or ‘Tyburn.’ No other details are given. One note says ‘Many sex scenes’ without further elaboration. It’s clear that the project was at an early stage of development and Bowie had yet to decide on the location or the storyline. He may have considered the satirical novelist Henry Fielding as a leading character. He transcribed this revealing quote from the socially ambitious author: ‘I’m the first in my family who can spell.’

He showed some interest in the Mohocks, a gang of upper-class ruffians whose antics fascinated and appalled Londoners. ‘Mohocks attack central figure,’ notes Bowie. They took their name from a Native American tribe and they behaved like an 18th-century version of the Bullingdon club. To amuse themselves, they pounced on strangers and played violent pranks but never stole money from their victims. The press publicised them widely during the spring of 1712 and their activities inspired a drama by John Gay. Their crimes were recorded by a witness, Lady Wentworth, who wrote that ‘they put an old woman in a hogshead [barrel] and rolled her down a hill; they cut off some noses, others’ hands, and several barbarous tricks without any provocation.’ As a commercial title, the word Mohocks has more to recommend it than Spectator which would not prompt a modern play-goer to think of 18th-century London.

Bowie saw it as a fertile source of material, and he listed the characters and pseudonyms used in the original Spectator

Bowie’s notes are full of unexplored avenues and paths not taken. A cryptic scribble says ‘November 5th. Burn the Pope. Kid collecting money.’ He’s referring to a British custom that seems to have expired in recent decades. Until the end of the 20th century, Bonfire Night was a much more significant date in the autumn calendar than Halloween. Families set off fireworks and ignited piles of refuse in their back gardens with an effigy of Guy Fawkes sometimes tossed onto the flames. There was no religious component to the ritual and, at least on the UK mainland, likenesses of the pope were not burned. The ceremony gave kids a chance to beg in public. In the days leading up to Bonfire Night, children would fashion a likeness of Guy Fawkes from discarded clothes, a paper mask and a Jacobean hat, and they used this prop to solicit donations from passers-by. ‘Penny for the guy,’ they called. Bowie doubtless witnessed this custom when he was young. He may have imagined a ‘kid collecting money’ as a character in his show.

His fondness for outsiders and folk-heroes is typified by his interest in the notorious thief Jack Sheppard, known variously as ‘honest Jack’, ‘gentleman Jack’ and ‘Jack the lad.’ His ability to escape from roundhouses, or jails, won him a following in the popular press. He managed to break out of prison four times, once in the company of his buxom consort, Elizabeth Lyon, known as ‘Edgware Bess.’ Bowie singles out this episode in his notes. ‘1724 Sheppard escaped from St Giles Roundhouse.’ Sheppard was hanged later that year. At his funeral, publishers sold copies of a fictional autobiography, said to have been written by Daniel Defoe. What a tantalising prospect: a Bowie musical about Gentleman Jack.

Bowie’s archive goes on public display this week at the V&A East. It’s amazing to think that he was compiling this material at the age of 68 while battling a terminal illness. A lesser spirit might have taken the easy route and created a juke-box musical called ‘Let’s Dance.’ But not Bowie. He was testing himself even as the darkness closed in.

Comments