What is art for? How can it, should it, relate to the political framework of its time? How far can it shade into ‘propaganda of the imagination’? These are some of the questions threading through Andy Friend’s compelling account of the first decade of the Artists International Association, or AIA, a vital but under-explored British movement welding art and politics against the growing threat of international fascism.

The story opens in 1933 in the candlelit rooms of Misha Black above Seven Dials, Covent Garden, where a dozen impecunious jobbing artists met to discuss a sensational report from the Soviet Union. This was that thousands of Russian artists were regularly employed and supported by the state, sponsored by trade unions or the Red Army, and that their work was published and widely exhibited, harnessed to celebrate the joys of Soviet life. This starry-eyed view of productivity and plenty landed among a group of disparate individuals disenchanted by years of struggling to find work and purpose in Depression-hit London, or dancing to the tune of dilettante art dealers.

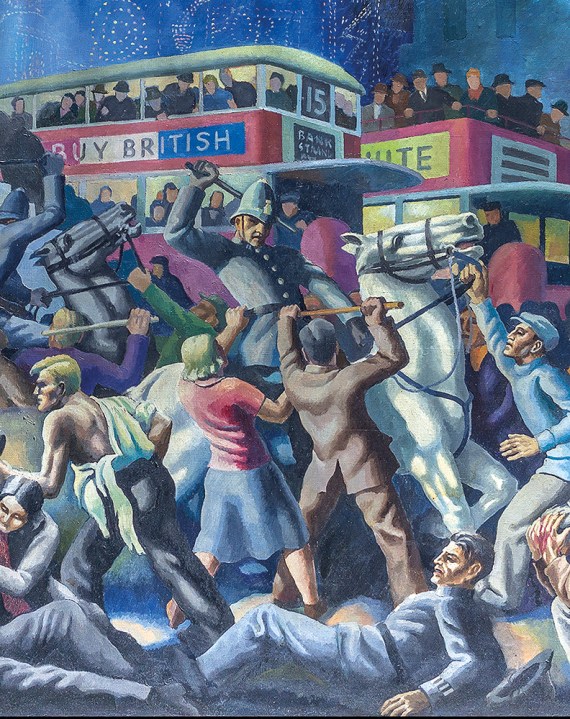

Little wonder, then, that it lit the blue touch paper, particularly as several artists present were politically radical. There was much to criticise in the government of Ramsay MacDonald; there were hunger marches and demonstrations, and while some were additionally attracted by communism, others were appalled by Hitler becoming chancellor that spring and feared the worst. ‘Artists International’ (the ‘Association’ came later) was conceived in response, and quickly grew in support, fired initially by charismatic and committed artists of real talent, many of whose reputations have sadly withered. Among the attractions of Friend’s survey are the superb illustrations, and the rediscovery of artists such as Pearl Binder, James and Margaret Fitton, Percy Horton and Cliff Rowe, now largely forgotten but in the vanguard of socially committed art at the time.

As the 1930s wore on, with the Spanish Civil War followed by rumblings of appeasement, an extraordinary web of connections formed between different groupings of artists, many newly politicised or catalysed by events, determined to set aside their aesthetic differences in a common cause. The aristocrat Jack Hastings had travelled to Russia and through Depression-era America before studying mural painting with Diego Rivera. Returning to London ‘a near communist’, he completed a vast mural in Marx House, Clerkenwell, to celebrate ‘The Worker of the Future Clearing Away the Chaos of Capitalism’.

Virginia Woolf, supporting her nephew Julian Bell (who would later be killed in the Spanish Civil War), fundraised for the AI. Later, Quentin Bell would serve on its central committee, and his mother Vanessa Bell and her partner Duncan Grant sat on its advisory committee throughout the war. Fred and Diana Uhlman made their Downshire Hill home a centre for refugees from the Reich and a powerhouse for disenfranchised artists before Fred was duly interned himself on the Isle of Man as an enemy alien.

The AIA advanced its aims by various means, primarily a series of high-profile exhibitions staged from Whitechapel to the West End, and later touring shows around the country in station ticket halls, canteens and libraries. The artists involved constitute a roll-call of mid-century talent, from Barnett Friedman, Victor Pasmore, William Coldstream and Paul Nash to Oskar Kokoschka, Julian Trevelyan, Carel Weight and Augustus John. Kenneth Clark, that enlightened pillar of the establishment, weighed in by instigating the War Artists’ Advisory Committee (WAAC) in 1940, commissioning the likes of Eric Ravilious to record landscapes of conflict, a brief that was to prove fatal in his case but which supported many artists throughout the theatres of war. The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact proved an ideological bombshell, given the latent communist sympathies of certain founding members of the AI. But Operation Barbarossa would swing back the dial, focus minds and strengthen members’ commitment to freedom, which would provide the theme of For Liberty, the crowning exhibition of the AIA’s first decade.

The chief pleasure of Comrades in Art is in encountering old friends in new guises, for the story has never been told in such detail before. The AIA destroyed its archives shortly after Dunkirk, fearing reprisals in the event of invasion. In stitching together such a lively account of its protagonists, Friend has corrected a significant apolitical bias in 20th-century art studies. Many monographs, as he points out, omit any mention of the AIA, or indeed the prevailing political climate. He also shows how the coming of war only increased the AIA’s impact and broadened its appeal, and how its artists negotiated the fine line between art and propaganda. This thought-provoking, readable and beautifully illustrated book is a huge contribution to our understanding of the cultural landscape in the mid-20th century.

Comments