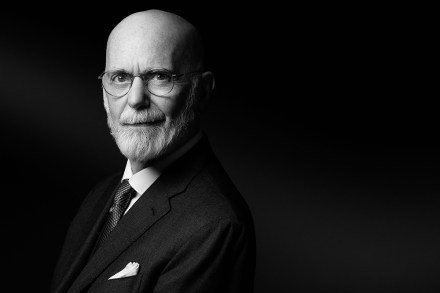

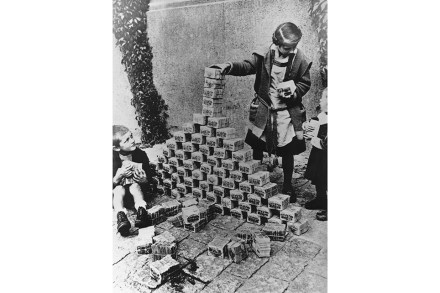

What did Leni Riefenstahl know?

Leni Riefenstahl: what are we to make of her? What did she know? Often described as ‘Hitler’s favourite filmmaker’, she always claimed that she knew nothing of any atrocities. She was a naive artist, not a collaborator in a murderous regime. This documentary wants to get to the truth. But even if you’ve already made your own mind up – I had! – it’s still a mesmerising portrait of the kind of person who cannot give up on the lies they’ve told themselves. Riefenstahl died in 2003 at the age of 101. A striking, Garbo-esque beauty in her youth she looked like a haunted Fanny Craddock by the end. She