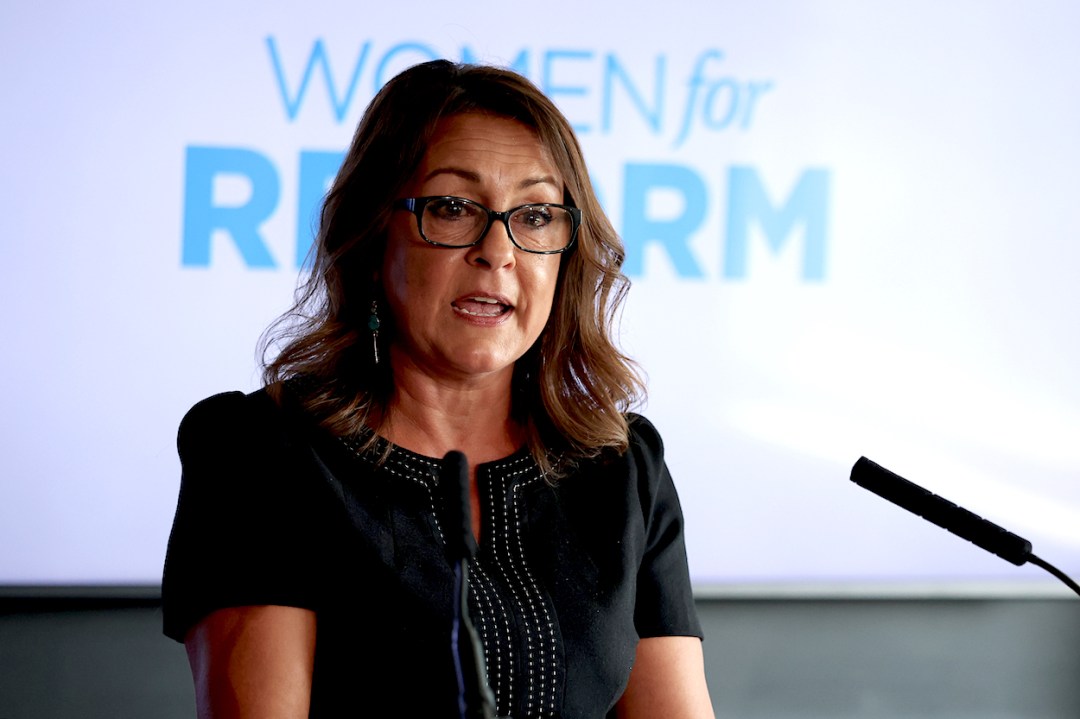

When Linden Kemkaran (formerly of The Spectator) was elected leader of Kent County Council, she presented herself as the poster-child for Reform in power. ‘The electorate,’ she said in June, ‘are looking to judge whether they can put their trust in a Reform government at the next election.’ Her administration set up ‘Dolge’, a ‘department of local government efficiency’, modelled on Elon Musk’s original, and instructed it to cut wasteful spending and find cash-saving efficiencies. After just five months, however, its efforts appear to have faltered.

The council is already ‘down to the bare bones’, Diane Morton, Reform’s cabinet member for adult social care in Kent, told the Financial Times yesterday. Reform has belatedly discovered that Kent, like many councils, has effectively become a care home provider that also collects the bins. Of every £100 the council spends, £35 of it goes on adult social care. The next biggest spend is children’s social care, on which £13 of every £100 is spent. As a result, Kemkaran’s administration will likely seek a 5 per cent increase in council tax. Reform in power, it seems, are a party of tax raisers.

Nigel Farage’s party is realising that cutting government waste is not the silver bullet that they had sold to voters. That’s not to say that government waste and inefficiencies should be ignored – there is an argument that the government should not be spending £500,000 on electric cars to give to the prison service of Albania, as the Spectator’s Project Against Frivolous Funding uncovered – but the uncomfortable truth is that most of what councils are spending their money on is mandated by central government legislation.

Duties to provide social care and special educational needs (Sen) services are crippling local government budgets. After Rachel Reeves’s first Budget, the Office for Budget Responsibility warned on page 129 of its 200-page fiscal forecasting document that the exponential rise in the number of children on so-called ‘education, health and care’ plans risked ‘some local authorities… [being] placed in financial distress or [being] unable to set a balanced budget’ – something they are legally required to do. An ageing population means the cost of caring for the elderly is also soaring. These are areas that Zia Yusuf, who runs Reform’s central Doge unit (which hasn’t yet been allowed to look in detail at Kent’s finances due to data protection issues), can’t just decry as ‘woke’ and cut.

Reform has work to do if it is serious about becoming a government-in-waiting. Talk of casually-dressed computer geeks slashing government waste will grab headlines, but it is nothing more than politics by meme. Even if every penny of wasteful state spending was eliminated, the public finances still wouldn’t be able to cope with the burden of demographic change, welfare dependency and ill-health. Any prospective government needs to be honest with the public about what the government is and isn’t able to do.

But there are ways forward. Wales, for instance, abolished the catch-all, ‘general’ category for schools reporting Sen – therefore forcing them to be specific about what learning difficulties their pupils had – and suddenly the number of kids entitled to Sen provisions collapsed from 23 per cent to 9 per cent. Measures like this are a tough sell, but a fiscal necessity. How Reform communicates these kinds of difficult choices to the public will be revealing.

Comments