Many Baby Boomers are sceptical about God. They think that believing in a higher power is probably incompatible with rationality. Over the last few centuries, religious belief has appeared to be in rapid decline, and materialism (the idea that the physical world is all there is to reality) has been on the rise, as the natural outcome of modern science and reason.

The majority of Gen Z respondents believe that you could be religious and be a good scientist

But if this scepticism is common among my older generation, times are changing. As we come to the end of the first quarter of the 21st century, the tables are turning – with scientific discoveries making people question the very things they took for granted and thought rational. Perhaps surprisingly, Gen Z are leading the way, purporting that the belief in God’s existence might not be just a trend on the rise – it’s a rationally sound conviction, in line with their attitude towards science and religion.

While the findings of Copernicus, Galileo, and Darwin created the impression that the workings of the universe could be explained without a creator God, the last century has seen what I call ‘The Great Reversal of Science’. With a number of break-through scientific discoveries – including thermodynamics, the theory of relativity, and quantum mechanics, plus the Big Bang and theories of expansion, heat death, and fine-tuning of the universe – the pendulum of science has swung back in the opposite direction.

More and more convincingly, and perhaps in spite of itself, science today is pointing to the fact that, to be explained, our universe needs a creator. In the words of Robert Wilson, Nobel Prize winner for the discovery of the echo of the Big Bang in 1978, and an agnostic: ‘If all this is true [the Big Bang theory] we cannot avoid the question of creation.’

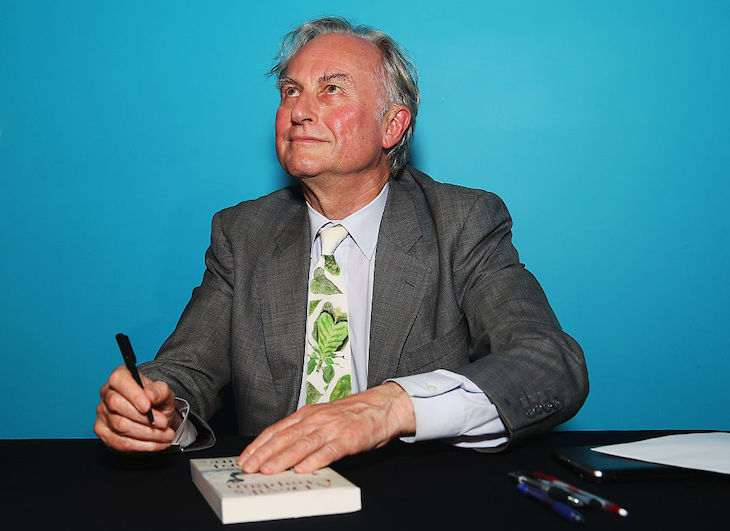

It is true that the existence of God cannot be proved incontrovertibly. While absolute proofs only exist in the theoretical domains of mathematics and logic, relative proofs are what we normally deal with, and what is generally considered ‘evidence’ in everyday life. If, like Richard Dawkins, we take a rational and scientific approach to the existence or non-existence of God, then we should only be persuaded by multiple, independent, and converging pieces of evidence.

Scientists across many fields of inquiry are now coming round to the idea that the thermal death of the universe and the Big Bang are strong evidence that our cosmos had an absolute beginning, while the fine-tuning of the universe and the transition from inert matter to life imply (separately) some more extraordinary fine tuning, showing the intervention of a creator external to our world.

With sets of converging evidence from different scientific disciplines – cosmology to physics, biology to chemistry – it is increasingly difficult for materialists to hold their position. Indeed, if they deny a creator, then they must accept and uphold that the universe had no beginning, that some of the greatest laws of physics (the principle of conservation of mass-energy, for example) have been violated, and that the laws of nature have no particular reason to favour the emergence of life.

Weighing up the evidence on each side of the scale is a matter of intellectual rigour, and the question ‘Is there a creator God?’ is one we should all be asking ourselves, with serious implication for every one of us. What’s intriguing is that it’s actually the youth, who you’d think would be more preoccupied with more mundane and practical concerns, that are leading the way.

Last August, a YouGov survey revealed that belief in God has doubled among young people (aged 18-24) in the last four years, with atheism falling in the same age group from 49 per cent in August 2021 to 32 per cent. Interpreting the data, Rev Marcus Walker, rector of St Bartholomew the Great in the City of London, mentioned that young people ‘seem really interested in the intellectual and spiritual side of religion’.

Another report from the think tank Theos revealed that Gen Z have a more balanced perspective towards the relationship between science and religion. Over one in two young people think religion has a place in the modern world, and the majority (68 per cent) of Gen Z respondents believe that you could be religious and be a good scientist.

Far from painting a picture in which the number of people believing in God is dwindling (which has been the usual narrative in the last century), this research suggests we are at the dawn of a revolution – one in which belief in God is not simply supported by science, but embraced by younger generations, too.

In general, Gen Z seems to have positive and hopeful view of science’s impact on the world. According to recent figures, 49 per cent of Gen Z trust scientists and academics the most to lead global change, far ahead of politicians (8 per cent) and world leaders (6 per cent) (WaterAid, 2025). And yet, they are still spiritually curious: their trust in science doesn’t preclude them from wanting to explore spirituality and contemplating something bigger than our universe.

Could they be the ones showing older generations a new way forward, one in which religion and science can coexist? And, more to the point, we now have the scientific evidence that would support a big shift in perspective. In the words of 91-year-old Carlo Rubbia, Professor of Physics at Harvard and Nobel laureate: ‘We come to God by the path of reason, others follow the irrational path.’

Comments