Pizza is the Italian food that has conquered the world. From Brussels to LA, from Beijing to Buenos Aires, pizzerias are everywhere. But what are the origins of this food, and how did it become so popular?

Reading Luca Cesari’sbook made me hungry not only for a thin crust margherita but also to digest the wealth of information about this simple dish. The margherita gets its name from Queen Margherita of Savoy, who, in 1889, on a visit to Naples, summoned Raffaele Esposito, the celebrated pizzaiolo (pizza-maker and hawker) to the palace to try his wares. She so liked the one with tomato, mozzarella and basil (made to represent the colours of the Italian flag) that it was dedicated to her.

For the lazzaroni,the homeless beggars of Naples, pizza was a subsistence food

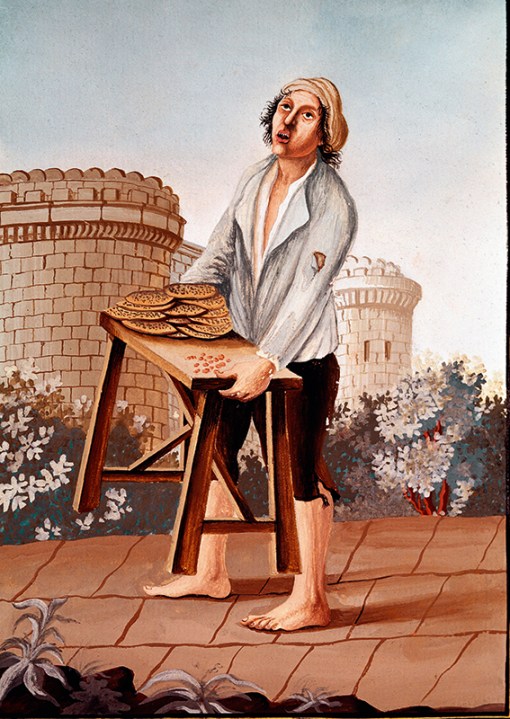

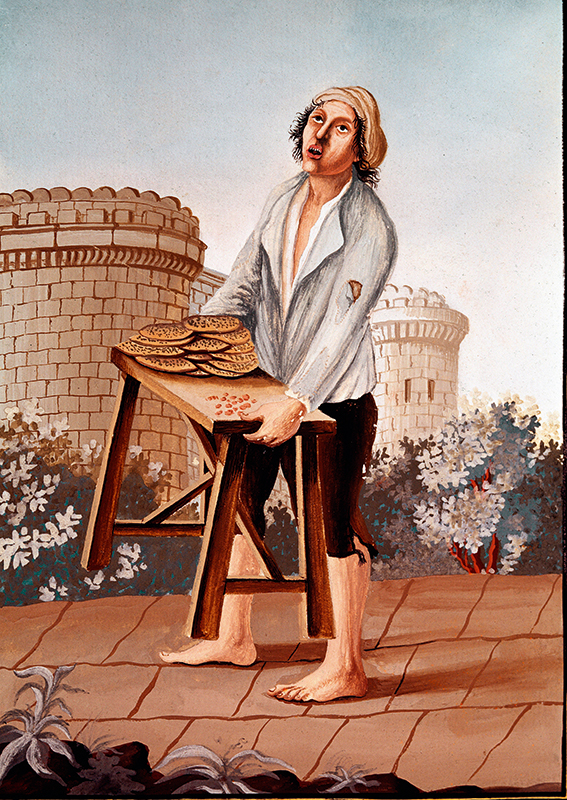

The story begins in the 18th century in Naples’s narrow alleys, where the impoverished inhabitants lived in a state of constant hunger. Early versions of pizza were simple flatbreads, sold by street vendors to assuage this problem. At that time, most people had no means of cooking a hot meal, and pizza could be folded and eaten on the spot. Sometimes the topping was just garlic and oil. Hawkers worked day and night and barely made a living, and neither did most of their customers. Cheap and versatile, the pizza remained virtually unknown outside Naples for more than a century, and the few outsiders who did encounter this strange flatbread, ‘more burned than cooked’, either loved it or loathed it.

But by the end of the century, with the growth of the middle class, restaurants began to appear. People wanting to meet friends but lacking a large enough house to accommodate them would gather in these places to eat simple dishes – such as pizza. A survey conducted in Naples in 1807 recorded 54 pizzerias. By the 1880s the number had doubled. The book’s illustrations show them as narrow booths, the tables separated by wooden partitions. During the day, the pizzaiolo would knead the dough, grate the cheese and de-stem the oregano. Then, as people left work and arrived at the restaurant, he’d cook the pizza in a woodfired oven on a ruoto (a wheel), a round baking sheet, and place it directly on the table. Wine would be brought in from outside by staff. The Neapolitan classic topping then was lard, cheese and basil.

Cesari takes us on a fascinating journey, covering the making of pizza and describing how the shape, dough and toppings evolved. Not all the recipes make your mouth water, particularly when the focus is on the poor hygiene of the early days. The history of Italy is served up almost incidentally – a tasty side to its most famous dish. I’d never heard of the lazzaroni, the homeless beggars of Naples for whom pizza was a subsistence food.

The author goes on to explore how, from such humble origins, pizza became one of the most lucrative foods on the planet. He records how gradually it spread to other parts of Italy. Like pasta, pizza is really just a base that, depending on the method of cooking and ingredients, can be turned into everyone’s favourite version. When it left Naples, the type of dough, its thickness and how it was cooked changed, as well as the toppings. In Tuscany, the flour was originally made from chickpeas and chestnuts.

Then, with the mass migration of Italians, pizza landed in the United States, where it enjoyed unprecedented success. Today, Americans are the biggest consumers in the world, at 13 kgs per head per year; and the global industry is worth more than $200 billion a year.

Who knew how fascinating a history of pizza could be? Cesari’s book transports us far beyond the wood stove and into the geographical, political and social context of what is so much more than the sum of its parts.

Comments