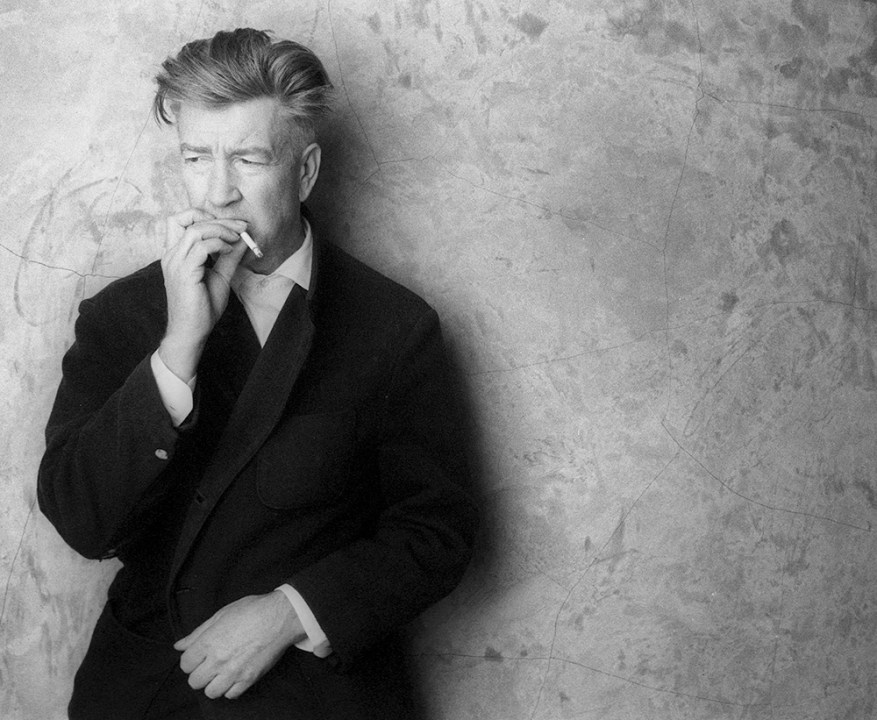

‘He was the true Willy Wonka of film-making – I feel like I won the golden ticket getting the chance to work with him!’ The speaker is Lara Flynn Boyle, who played Donna Hayward, the friend of the murdered Laura Palmer in David Lynch’s small-screen masterpiece Twin Peaks.

That comparison, cited in John Higgs’s terrifically lucid and compact study of the filmmaker, who died in January, aged 78, is rather brilliant. Plenty of actors might feel they’ve won a golden ticket in getting to work with some famous director, but none of those others get to be described as Willy Wonka: a genius with a dash of eccentricity, enclosed in the walled compound of his own reputation; an artist-craftsman dedicated to the continued manufacture of mysteriously delicious treats made to his own recipe and also just the littlest bit disturbing.

Higgs points out, incidentally, that not all actors considered working with Lynch a golden ticket. When Lynch screamed at him in a fit of rage during the filming of The Elephant Man (this was before the sustained practice of transcendental meditation calmed the director’s temper), Anthony Hopkins reportedly tried to get Lynch fired and had to be talked down by the producer, Mel Brooks. And for all that he was a one-off, Lynch certainly availed himself of the traditional Great Man prerogative of serial monogamy and many ex-wives. Higgs facetiously, or maybe quite seriously, says that ‘the love of Lynch’s life was Sparky, a terrier he owned in the 1980s’.

This bookis an unassumingly intuitive and insightful brief history, whose title succinctly implies that Lynch was under a spell as well as casting one. You can read it in about an hour and it will tell you more about his life and filmmaking than a thousand interminable academic studies and PhD theses. In his canteringly readable prose, Higgs takes you through Lynch’s Eisenhower-era boyhood, the family moving from Montana to Idaho and Virginia, and then his conversion to the vocation of artist – for which film was to be a constituent part, along with music and photography – and his fine-art studies in all the urban scuzziness of Philadelphia, an environment which was to be quite as formative as wholesome smalltown America.

Lynch became an instant cult smash with his dreamlike body horror Eraserhead (1977), which ruled America’s midnight-movie circuit and announced him as the most important movie surrealist since Buñuel. He followed it with the more conventional but much admired The Elephant Man (1980), with John Hurt as John Merrick. He stumbled with his uncertain sci-fi adaptation of Frank Herbert’s Dune (1984), but made triumphant repeated returns to his psychological home turf, his Lynchian surreality: the eerie picket-fence loveliness of white conservative America in which lurks a distinctively apolitical kind of darkness and violence.

Eraserhead announced Lynch as the most important movie surrealist since Buñuel

This was the disquieting drama of Blue Velvet (1986) and the extraordinary TV series Twin Peaks (1990), which spawned a feature sequel, a second series and then a complete extended new series in 2015: a small-screen franchise whose weirdo aesthetic owed something to The Twilight Zone, but whose artistic ambition was the precursor of later TV hits such as Mad Men, Breaking Bad and Severance.

Lynch’s sexily violent runaway in Cannes’s Palme D’Or winner Wild at Heart (1990) anticipated Quentin Tarantino; his sinister VHS tapes in the neo-noir Lost Highway (1997) anticipated Michael Haneke. A more straightforwardly sentimental oldster tale, The Straight Story (1999), was respectfully received. But the real excitement was reserved for his LA psycho-mystery Mulholland Drive (2001), with Laura Elena Harring and Naomi Watts, which was narcotic and erotic. (Actually, a minor quarrel I have with this book is that it slightly overlooks the eroticism.) A later film, Inland Empire, from 2007, was lower budget but still fascinating and scary. The rest of his life and career was expended on various other projects and his passionate dedication to smoking (surely part of his meditative habit) until the revival of Twin Peaks.

The main event of Lynch’s young life – the main event of his artistic inspiration – is also the main event of this book. As a child of maybe 12 or 13, playing out in the street with his brother John, the young David was astonished to see a naked, beautiful woman stumble up to them, dazed, bruised and bleeding and sit down on the kerb, evidently in shock. The Lynch boys did not have the maturity to understand what was happening – clearly the woman was a victim of domestic abuse. John burst into tears, but David did not – transfixed, horrified, even strangely exalted by the sight, which was preserved in its epiphanic strangeness by his own innocence and naivete. Or did he exaggerate that crucially uncomprehending naivete in retrospect? Who knows? Either way, it planted the radioactive seedling. Lynch’s movies, Higgs persuasively argues, are based on images, moods and ideas, flowering and metastasising from below into dreamscapes.

Higgs says that critics casually use the word ‘Lynchian’ without acknowledging that nothing is really ‘Lynchian’. Nobody was really influenced by him; nobody could be. I know what he means, although, as I say, he got to some images and ideas in the 1990s before other people. And perhaps Higgs could have talked about the proto-Lynchian movies that influenced him: The Wizard of Oz, and the films of Douglas Sirk. Martin Scorsese’s Shutter Island is pretty Lynchian, sharing the same modernist narrative trick-loop as Mulholland Drive (both Scorsese and Lynch were, at different times, in a romantic relationship with Isabella Rossellini); and maybe the most obviously Lynchian director is Steven Spielberg, for whom extra-terrestrials were at home in American suburbia. It was Spielberg who had the inspired idea of casting Lynch as John Ford in his autobiographical movie The Fabelmans.

Higgs dwells on the bizarrest Lynchian aftershock. The director dismayed his progressive fanbase by claiming that Donald Trump could be a great president because ‘he has disrupted the thing so much’. A very overexcited and muddled Trump seized on this comment and told a rally: ‘David Lynch could go down as one of the greatest presidents in history!’ That suit, that long red tie, that strange quiffy hair. He looks like a minor nightmarish villain for whom only one adjective is applicable.

Comments