The National Curriculum Review, published earlier this month, was a rare opportunity to ask some fundamental questions about the purpose and outcomes of British education. It is an opportunity that has been missed.

In some ways, the review has a laudable conservative tenor. It is, for the most part, grounded in practical evidence rather than blind ideology. It acknowledges the improvements in literacy and numeracy brought by the previous government’s reforms, and calls for incremental rather than radical changes.

However, it fails to grapple with the connections between education and society’s most fundamental problems. No one can deny that the country is in the grip of a mental health crisis, especially amongst the young. This goes hand-in-hand with the ingrained spiritual nihilism of many British institutions: the de facto denial that there is anything more to life than economics.

In addition, there is a crisis of national identity. This is manifest in the obvious decline of shared cultural and historical knowledge and bitter disputes about the nature of Britishness. This is no abstract conundrum. Without a settled notion of common culture, the idea of social cohesion will be a chimera.

The review pays lip-service to these problems. Education is important, it says, not just for building ‘a prosperous economy’ but also a ‘flourishing civil society, and in promoting social cohesion and democracy’ as well as the ‘spiritual and moral’ development of the young.

However, it is scanty or unrealistic in how to reach these goals. The ideas of the spiritual and moral are unexplored. Education about citizenship is to be improved primarily by the further development of practical skills and knowledge, for example financial, digital and media literacy (‘we already do this,’ grumbled one teacher I spoke to). Cohesion is somehow to be won by the continued incantation of the watery ‘British Values’ whilst at the same time racing to ‘reflect our diverse society’.

Two reports released this week suggest how different and how much better things could be. First, Civitas authors Briar Lipson and Daniel Dieppe have put forward a call for ‘Renewing Classical Liberal Education.’ This does not mean that every school pupil should be packed off with a copy of Kennedy’s Latin Primer. Rather, that education should have at its heart the cultivation of wisdom and virtue, the pursuit of truth and the appreciation of beauty.

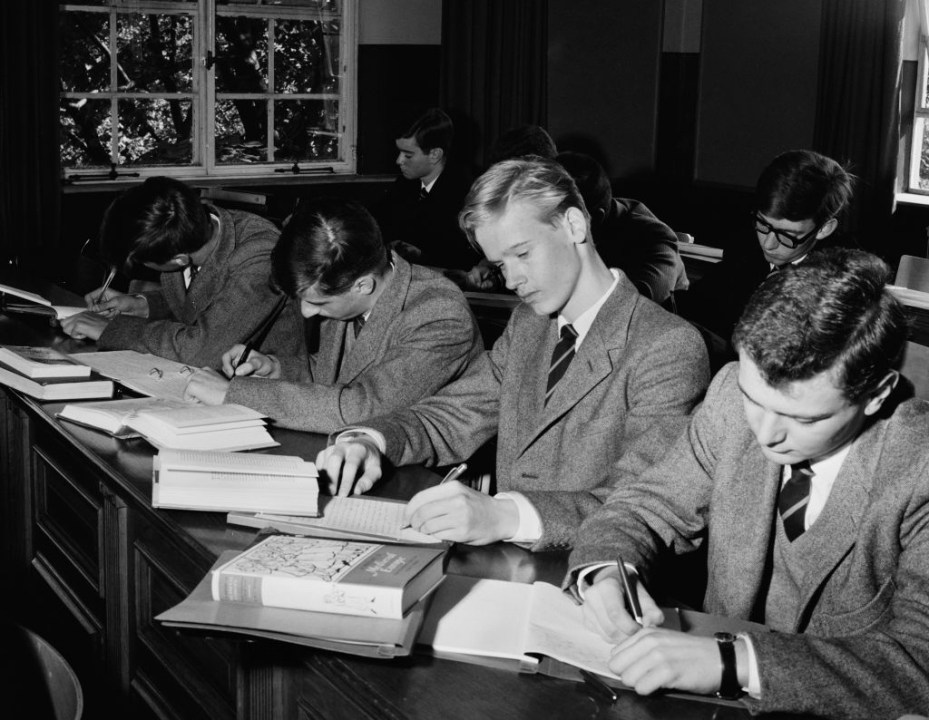

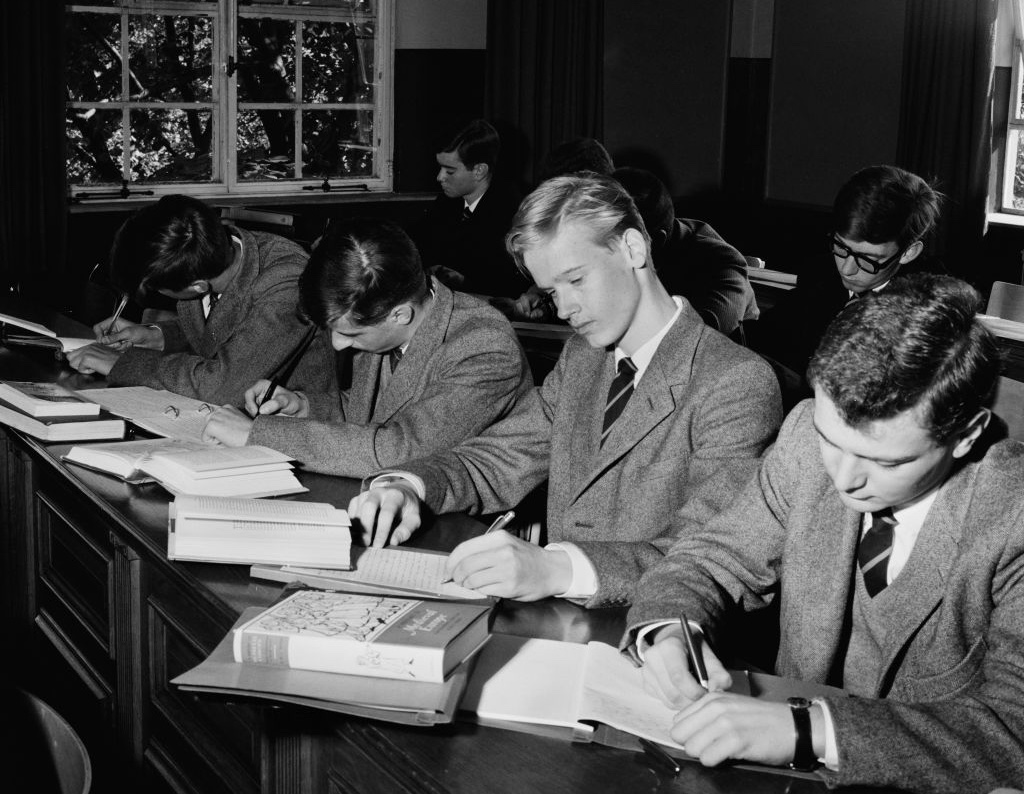

These were ideals that had been at the centre of educational theory since the classical age, only ebbing in the mid-20th century. They were ‘liberal’ as they fitted the student for life as a free person with independence of mind. They cherished the thirst for the spiritual and beautiful. Their cultivation was pursued by engagement with the best and most profound texts of the inherited canon, accumulated over 2,500 years. These might start with Homer, the Greek tragedians and Plato, go by way of biblical scripture and St Augustine, to Chaucer, Shakespeare, the metaphysical and romantic poets, to Jane Austen, Dickens, George Eliot, and more modern writers who have drawn from the tradition such as Gerard Manley Hopkins and T.S. Eliot.

The Curriculum Review seeks to maintain the requirement for pupils to read a Shakespeare play, a 19th-century British novel and a work of post-1914 fiction. This may sound like it is rigorous and designed to ground pupils in a tradition. However, the Civitas report shows the reality of the situation is that over 80 per cent of 14-to-16-year-old GCSE students study J.B. Priestley’s An Inspector Calls as their non-fiction text – a mere 72-page pamphlet with a simplistic call for socialism – and that 70 per cent study Dickens’s A Christmas Carol – a novella with a recommended reading age of eight to 12. The easiest, shortest texts are chosen for study, with questions strongly focused on literary technique rather than substance. Teaching to the test elbows out the contemplation of any more profound questions.

The Civitas report shows how, with ambition and vision, a liberal education of real breadth could be reintroduced. American Classical schools, from year three in primary school, introduce pupils to everything from Shakespeare to Tennyson, Coleridge, Marlowe, Beowulf, Virgil, Greek and Egyptian myth. Pupils are encouraged to see the continuities and connections throughout generations. Their exam questions focus on discussions of morality, virtue, beauty, the purposes of life.

The knowledge of a literary canon helps to assuage our spiritual needs. It also contributes to an understanding of our national identity. A second report, by the Foundation for the History of Totalitarianism, draws attention to the collapse in pupils’ knowledge of British and world history. For the former, fewer than one in five were ‘significantly familiar’ with ‘key events such as the Norman Conquest, the signing of Magna Carta and the Battles of Trafalgar and Waterloo.’ Three quarters don’t know about Admiral Nelson, and half about Oliver Cromwell.

‘We do not teach schoolchildren about the greatest heroes of our collective past,’ observes Andrew Roberts in the report: ‘This leads to a form of national cultural suicide.’ We ignore this warning at our peril. The incantation of bloodless and abstract British Values will not hold our society together. We need our heroes, and our stories.

John Milton wrote that ‘A good book is the precious lifeblood of a master spirit, embalmed and treasured up on purpose to a life beyond life.’ Now is the time for the transfusion of good books back into our education system. This is the only way back to health.

Comments