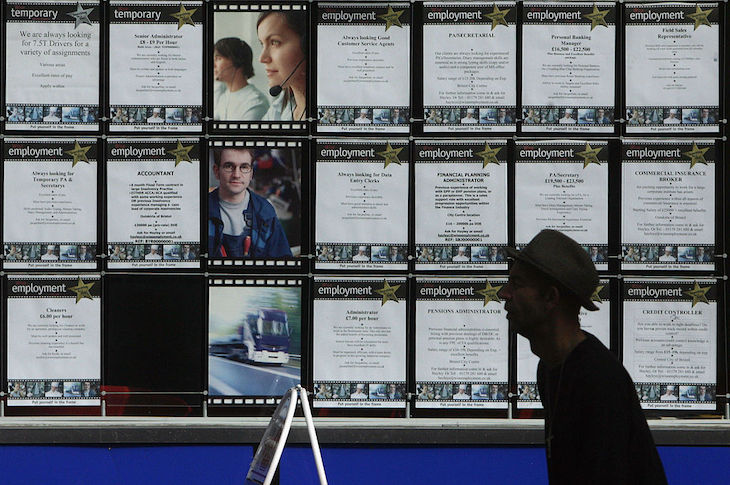

Work is good. Work generates wealth, makes people happier and, maybe, delivers salvation. The Protestant work ethic is much disputed among sociologists and economic historians, but most people accept that some level of work is both necessary and desirable. This makes it all the more troubling that, buried in the OBR data under the Budget, are signposts to a future Britain where fewer people work at all – and where those who do are working less.

The Office for Budget Responsibility says the labour force participation rate is forecast to fall ever so slightly, from 63.5 per cent in 2024 to 63.4 per cent in 2029. A tenth of a percentage point over five years is not huge. But thinking about the economic future, does anyone think that Britain needs the share of the population that’s not working to be rising?

The story of the Budget is the faintly tragic tale of a country drifting away from work

And the OBR’s footnotes tell a sobering story: participation is falling because Britain is ageing and getting sicker. Long-term sickness keeps rising and is pushing up incapacity benefit caseloads. This is not the country becoming more efficient and so able to make do with fewer workers; it’s a nation quietly becoming less able to work.

The OBR does identify three big forces acting in the opposite direction, but none are simple positives. First, ageing will require more people to work later: the state pension age rising from 66 to 67 between 2026 and 2028, keeping some older people in the labour force for a little longer. That’s necessary but may well be divisive, as higher earners (and public sector workers) will be able to amass pensions allowing them to retire sooner, while the poor toil on.

Second, falling birth rates: some women won’t leave the labour market because of childcare – but that will eventually mean fewer young workers to support our more numerous pensioners.

Third, migration helps too, because migrants tend to be of working age. But it’s worth noting that the OBR’s entire forecast is based on the estimate that net migration will rise to 340,000 a year by the end of the decade.

If by 2030 Britain has a government that seeks to lower migration levels significantly below that – a far from implausible scenario – the total available British workforce is likely to be smaller still. I’m pretty liberal on immigration, but I’m also a political realist – basing economic policy on migration numbers that can’t command political or public consent is nuts.

Even the OBR’s more upbeat Labour force revisions have a melancholy undertone. Its latest estimate of participation and employment in 2024 and 2025 is 0.5 percentage points higher than previously thought, thanks to improved ONS survey data. The much-criticised Labour Force Survey is getting a bit more reliable, the OBR reckons.

Better data now produces a more reassuringly consistent picture across payrolls and surveys, and total employment is forecast to rise from 33.9 million in 2025 to 35.2 million in 2029. In another country that might feel like a success story. In Britain, our lousy official data mostly means we have rediscovered workers who were always there but didn’t show up in the stats.

And then there is the matter of hours worked. The OBR expects average hours worked to fall from 32.0 in 2025 to 31.8 in 2029. Again, 12 minutes a week sounds trivial until you multiply it across 35 million workers. That gentle downward drift is the result of the population ageing: older people work fewer hours, and Britain is becoming a country of older people. A nation that once prided itself on long days and longer commutes is quietly slowing down, taking it a bit easier.

Put all this together and we glimpse the shape of future Britain: not a four-day-week utopia but a country where labour participation falls slowly and workers work less. The harsh arithmetic of an ageing society means more pensioners, more sickness, more fiscal pressure, and fewer workers working fewer hours. The slope is gentle, but the direction is downwards.

A country that needs more people to work requires a welfare system that encourages them to do so. The Budget confirms that most Labour MPs are yet to accept this, but if any minister can change that, it will be Pat McFadden at the Department for Work and Pensions.

For now though, the story of the Budget numbers on work is the faintly tragic tale of a country drifting away from work.

We’re not alone in this: most other advanced democracies will face similar challenges. But that doesn’t change the basic facts for Britain: unless we find ways to bring more people into the labour force – and keep them healthy enough to stay there – the long-term future is lower growth and higher taxes.

So whoever is in power after the next election will face a stark choice: find a way to deliver more workers who do more work – or embrace decline.

Comments