Bruckner at the Wigmore Hall. Yes, you heard right: a Bruckner symphony – his second: usually performed by 80-odd musicians – on a stage scarcely larger than my bedroom. How? Welcome to Anthony Payne’s very smart 2013 chamber arrangement. Bruckner on Ozempic.

Composition is an Alice in Wonderland activity. A key duty is mastering how to make things bigger and smaller, how to stretch and compress and bend – time and space and sound. Bruckner understood this. If you know anything about his symphonies, it’s that they’re vast – and that critics are mandated to compare them to cathedrals or mountain ranges. What survives after such an extreme trim? More than you expect. The long sightlines remain; paradoxically, the reduced forces sharpen the sense of depth. Even the symphonic atmosphere is hard to shake off when you still, as here, have a timpanist in play. Feel that kettle-drum rumble and it’s impossible not to believe you’re in the presence of a full orchestra.

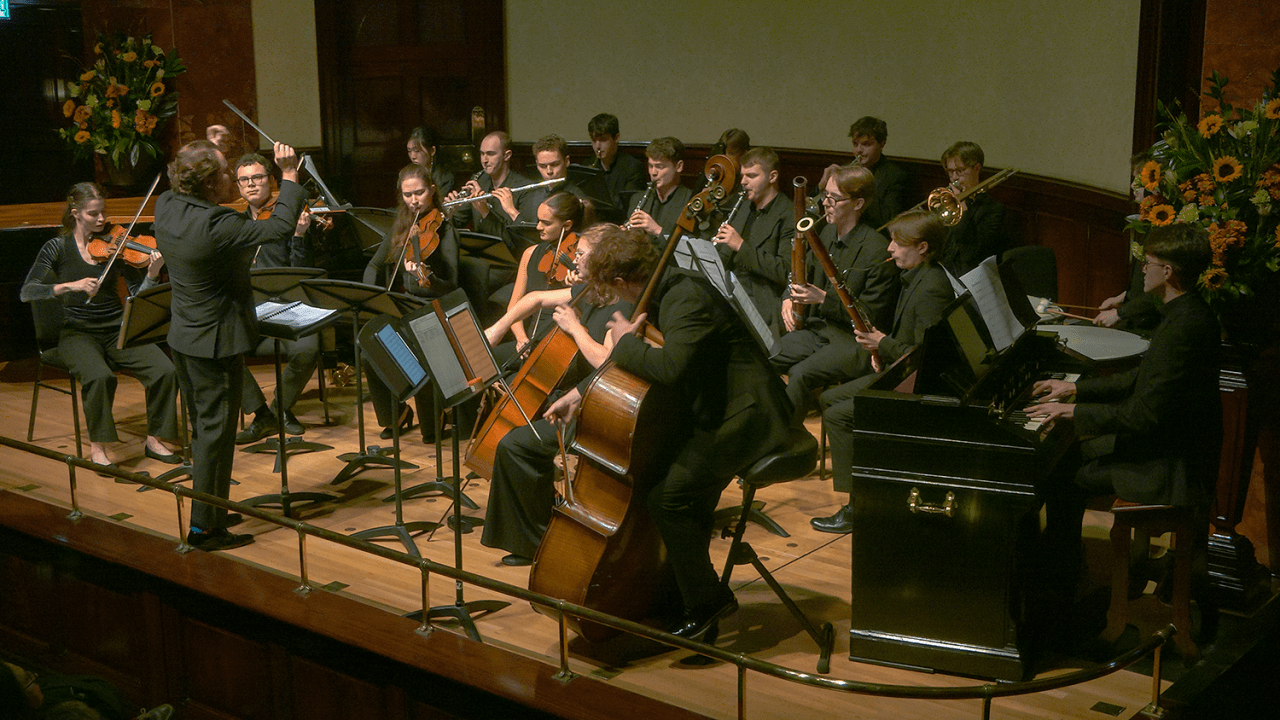

But lean, hench Bruckner is still something to behold. Look how lithe his hips become. This was an impish Bruckner 2, a seedy harmonium wheezing mischief and threat. A fiercely committed ensemble of soloists from the Royal Academy of Music made the lyricism count too (baffling that the work’s first conductor believed the work lacked melodic interest). Skinny Bruckner is also Bruckner in which you can do hand-break turns, and conductor Jonathan Berman took every opportunity to send up puffs of smoke as he slammed down the gears. Exhilarating stuff.

Symphonies, as Haydn conceived them, were made for halls this size. Listen to Il Giardino Armonico letting loose two of Haydn’s symphonies in the intimacy of the Wigmore Hall a few weeks later and you’ll wish it was always this way. They opened the concert, however, with Matthew Locke’s extraordinary overture to a 1674 semi-opera of The Tempest: melody, harmony, rhythm cut from its moorings, buffeted by invisible gusts in a way that Cage might have saluted. Later came Samuel Scheidt’s ominous musical grisaille, Paduana dolorosa (1621), sculpted to perfection. The problem with the 17th century – the most experimental before the 20th – and why we hear so little of its music is that it’s still all too weird for us.

Giovanni Antonini conducted with his arms outstretched, like a boy playing aeroplanes. The Haydn symphonies (nos 44, the Trauer, and 52, which I like to call the ‘Schizophrenic’) soared accordingly, making darting, acrobatic turns, capricious and moody, the strings bouncing about with the most satisfying crunch, like a skier slaloming through dense snow. Antonini and his band are halfway through recording the complete Haydn symphonies. Seek them out. Hard to think of anyone doing them better.

What happened to the symphony? It endures at the edges – in Finland and America; Philip Glass is on his 15th, god help us. But in its birthplace in central Europe, it’s practically extinct, or at least in hiding. Those who have kept the flame alive, curiously, include several experimentalists, who, like the surrealists, love reclaiming obsolete forms. Take John White’s Haydnesque Symphonies 3–6 (1981): each one eight minutes long, four movements apiece, scored for nine including a timpanist. They’re funny, mad, cheerfully vulgar little things: a world of gameshow music, 19th-century ballet and Saint-Saëns. Like rummaging through an old drawer full of gunky coins, scuffed postcards, pretty marbles, mystery plastic debris.

‘Each symphony represents an attempted “improvement” on its predecessor,’ White writes. So the four movements parade past in four different costumes, increasingly confidant, increasingly odd. The fabulously named ensemble George W Welch – at the equally fabulously named concert series Music We’d Like To Hear – brought out all the eccentricity without succumbing to any eccentricity themselves.

More music we like to hear at Milton Court – from Explore Ensemble and the astonishing voices of Exaudi. Catherine Lamb is an American microtonalist. What this means in practice is that she writes music that’s out of tune – as did all Western composers before the 18th century. And she has mastered this art of ‘just intonation’ in a way that allows her to inhibit a space that feels both familiar – ancient, eternal – and otherworldly. In dying your dying to come closer limpid song drifts out of a microtonal fog. Vaporous, rich, hallucinogenic. Cryptic incantations, warnings (courtesy of Ursula Le Guin) spill forth in the most pure, unforced tones. A bridge between distant future and distant past is forged.

The clouds clear to reveal an oasis at the work’s centre: fat, jangly, iridescent droplets of sound falling from a plucked electric guitar and Celtic harp. Before long, we’re forced back into the mist. Gently disquieting, quietly stirring, celestial, Sphinx-like: I can’t think of another composition quite like it – nor a finer première this year.

Comments