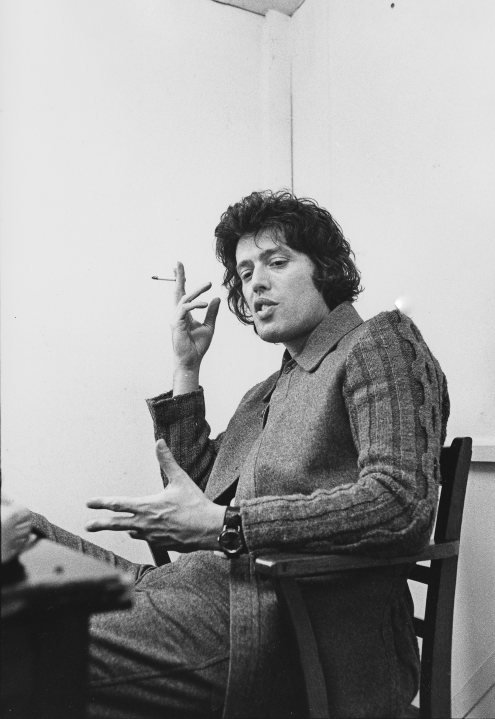

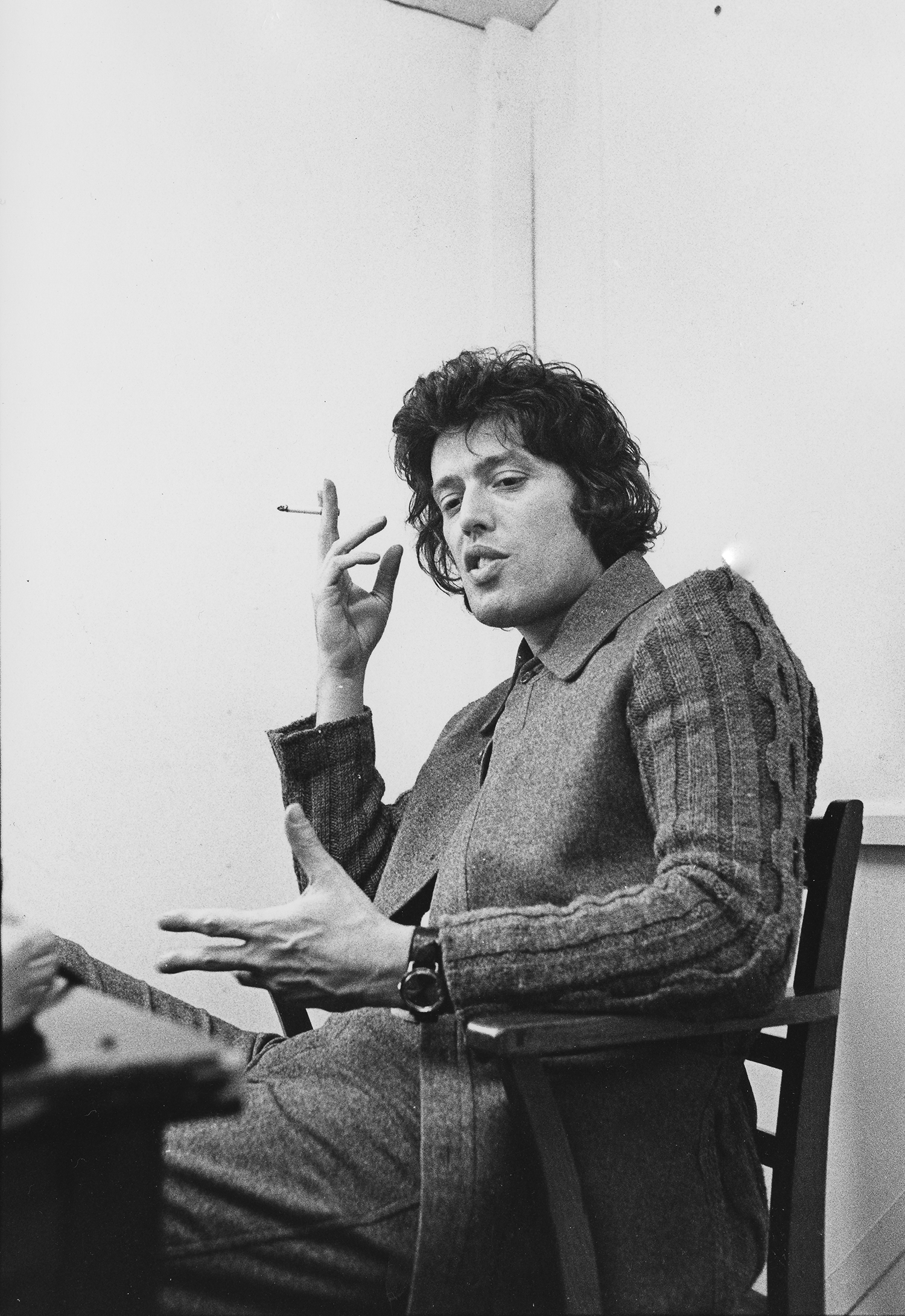

The playwright Peter Nichols created a character based on Tom Stoppard. Miles Whittier. On a car journey across London, I once asked Peter why he was so irked by Stoppard. Thelma, his wife, answered for him: ‘He uses all the oxygen.’ But Stoppard was miles wittier. Asked by a punter, after the New York first night of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, what his play was about, he replied: ‘It’s about to earn me a great deal of money.’ Think about it: the only person capable of preserving that bon mot was the playwright himself. He knew how funny he was. Later, he was more careful. Asked by Melvyn Bragg on Start the Week, what the play was about – it was revived with Adrian Scarborough and Simon Russell Beale – Stoppard explained that it was his son Barnaby’s set text at GCSE, so Stoppard had given his son the benefit of the author’s insight. ‘He got a C.’

After Pinter won the Nobel Prize, he lobbied his playwright friends to get a West End theatre named after him. When he rang Stoppard, Stoppard said it would be easier to change his name to Harold Comedy. (In the end, the Comedy Theatre was renamed the Harold Pinter Theatre.) I asked Stoppard at one of his famous biannual noon-to-sunset parties in the Chelsea Physic Gardens – jazz band, string quartet, Punch and Judy, oyster bar, hamburgers, performers on stilts, tumblers, jugglers, once a caviar bar – if the story was apocryphal, as I’d always assumed. He looked away and said in an undertone: ‘Not so apocryphal.’

He gave the Isaiah Berlin lecture at Wolfson. The crowd was so large it overspilled the hall, so it was broadcast on speakers to the students crosslegged on the grass outside – who complained when the ad hoc set-up failed. There were several reprises and Stoppard improvised a routine with the don who was responsible. During one repair to the sound system, it was established that he worked in the physics department. At the next breakdown, Stoppard asked him what the academic status of the physics department was: ‘Modest, I assume, judging by today.’ It could have been a disaster. It was hilarious. Finally, after yet another fix, Stoppard said to the physicist: ‘I was up all night writing this next bit. If you mess it up, I’ll kill you.’ It was actually a long speech about the importance of art from Travesties. Funnier, though, if you say you wrote it last night, not 30 years previously.

At the dinner afterwards, my wife was on Tom’s left. I was opposite. A quite frail Aline Berlin was on Tom’s right. As he talked to me, he reached across and took both of Aline’s hands in both of his hands. Tenderness and love – wordless, natural, intimate, inevitable and very moving. She might have been his mother.

My wife wanted to tell him he was the best playwright since Shakespeare. She resisted. I wrote to him about the repressed impulse, adding that, even for him, a man accustomed to receiving fulsome compliments, it might have been difficult to respond. He wrote back brilliantly, ‘surely she means since Aeschylus?’.

We are used to the idea that our greatest writers might be unpalatable in person. Not Stoppard

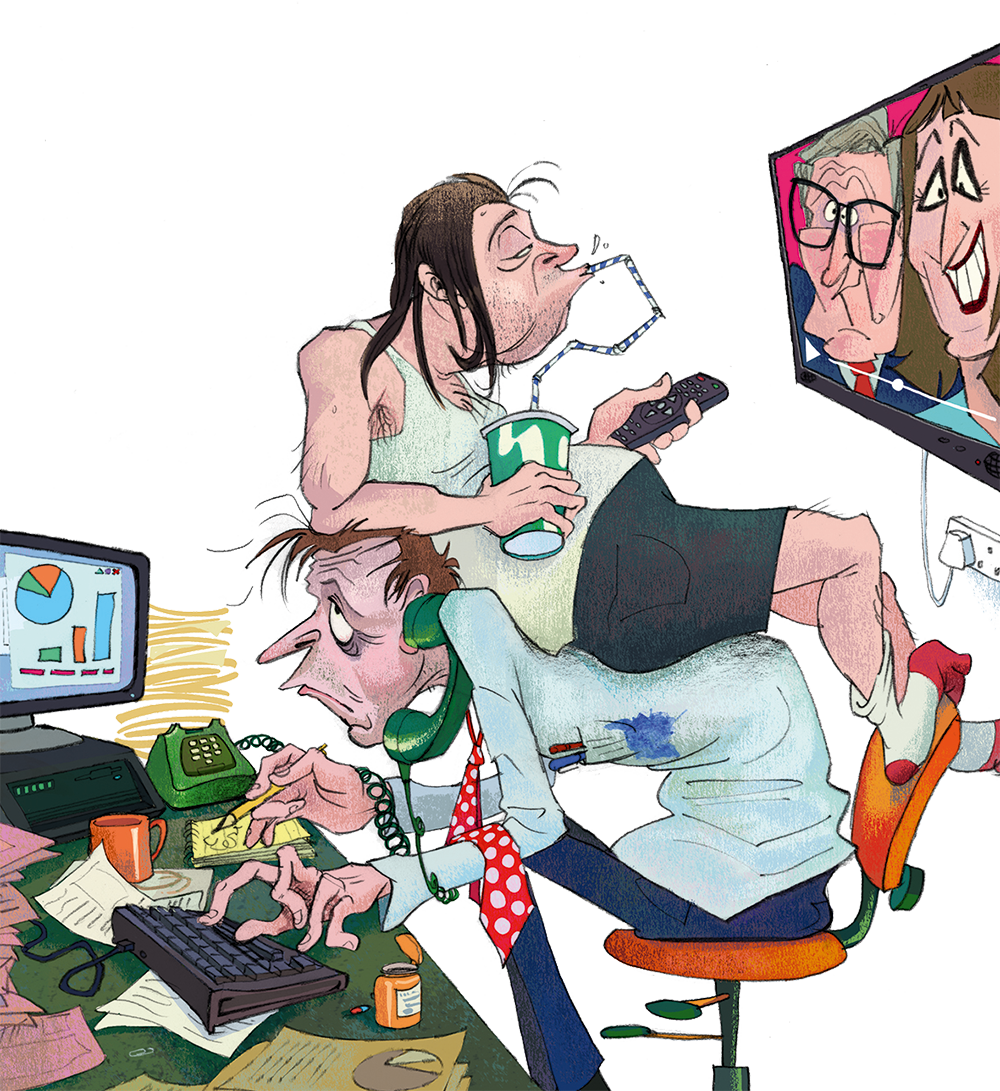

The Isaiah Berlin lecture leads me to reflect on the way his plays break the rules. The easiest plays to stage are two-handers, with pithy exchanges of dialogue. You don’t want speeches. Stoppard’s plays are full of speeches. Travesties begins with a speech lasting four and a half pages. The cast of his trilogy The Coast of Utopia runs to about 50 at a guess. There are 27 characters in Part One. When my daughter Nina was in Moscow with Stoppard, covering the rehearsals of the play, Stoppard was anxious to keep the comedy alive. He said: ‘I really want to write a play for circus performers. There would be a scene where the wife throws a knife at her husband’s ear and it would stick in the cupboard, and the wife’s lover would run across the clothes-line… The more serious the subject is, the more like acrobats, trapeze artists, jugglers you have to be. The serious things the play is about don’t need looking after. If that was what we are here for, I’d write an essay, not a play.’ A bit like a Tom Stoppard party, then.

Though there aren’t any essays, there are many lectures in Stoppard’s plays. The philosopher George is writing a lecture in Jumpers. Housman delivers a lecture at the end of Part One of The Invention of Love. In Professional Foul, Anderson, the philosophy professor, improvises a lecture on ethics. Squaring the Circle, Stoppard’s TV play about Solidarnosc is really a lecture with slides. But they are all brilliant, exceptional lectures. Artificial, because they’re word-perfect, but delivered dramatically, naturalistically by actors. A lot depends on the actors. I doubt if anyone will match Tom Hollander’s virtuosic Henry Carr.

We are used to the idea that our greatest writers might be unpalatable in person. Not Stoppard. In 1980, I published a pamphlet with four poems. One was called ‘The Season in Scarborough 1923’. Tom sent me a watercolour of the town. I was with Patrick Marber when he took a phone call from Tom. He was ringing from his mobile outside the Sydney Opera House where he had just seen the première of Patrick’s play for schoolchildren, The Musicians. A lovely man and a great writer.

Comments