In 1755, Samuel Johnson (this was before his honorary doctorates) defined the herring as ‘a small sea-fish’, and that was it. By contrast, Graeme Rigby has spent 25 obsessive years documenting the cultural and economic importance of this creature. The resulting omnium-gatherum is like the bulging cod-end of a bumper trawl net, farctate with glistening details that embrace zooarchaeology, cooperage, otoliths, skaldic verse and Van Gogh’s ear.

Clupea harengus is a highly adaptable, widely distributed marine teleost that can form shoals covering several square miles, and their milky spawning trails are so long they can be seen from space. The name may derive from the Germanic heer (army), and its nicknames include ‘Digby Chickens’. In Greenland, you should ask for Angmagssagssuaq. The book’s sub-title alludes to the ‘King of Fishes’, and the author confidently states: ‘Some claim salmon is, but they’re just riparian hobbyists.’ (There go centuries of angling literature, then.)

Rigby cites many of his precursor ‘herringists’, but his twin cynosures are that protean pamphleteer Thomas Nashe (in particular his 1599 Lenten Stuffe) and Paul Neucrantz, the author of a ‘medico-historico-zoological treatise’, De Harengo (1654). Rigby’s own scale of reference is vast and includes Flemish still life, contemporary sculpture, economic history, biology, legend and folk song. It is a veritable ‘ency-clupeidae’ (the coinage is mine), charting the rise and fall of various distinct fisheries (Icelandic, Norwegian); developments in commercial techniques (such as the preparation of red herrings, an odiferous, heavily salted, cold-smoked staple); slave provisioning; the first factory ships (15th-century Dutch ‘busses’); the vagaries of fasting customs; basket weaving; boat design; and how in their heyday the ‘silver darlings’ were a source of gold. We get a bit bogged down in the Anglo-Dutch wars and then international quotas, but who doesn’t? Overall, Rigby’s alphabetically arranged, neatly cross-referenced entries are nuanced, learned and admirably digressive. There’s even an ancient joke: ‘Why are Protestant martyrs like red herrings? Because they’re hanged and burned.’

Along the way we are introduced to Thomas Aquinas and his herring miracle; Holinshed’s Fastolfe and the Battle of the Herrings in the Hundred Years’ War (didn’t Shakespeare’s fat knight describe himself as ‘a shotten herring’?); two sottish Renaissance clown figures, Pickelhering and Hans Stockfish (salt herring was dished out in taverns to provoke thirst); mock encomiastic verse from J.K. Huysmans (‘O, shimmering and smoky…’); and the ‘sexual frisson’ underlying Benjamin Britten’s comic opera Albert Herring. There are also work songs from the itinerant ‘Herring Lassies’ (not to be confused with coarse, Billingsgate-language fishwives), who could gut 40 fish per minute with their sharp futtles and raw, bandaged fingers. One girl said: ‘I sometimes think we sang to stop ourselves crying.’

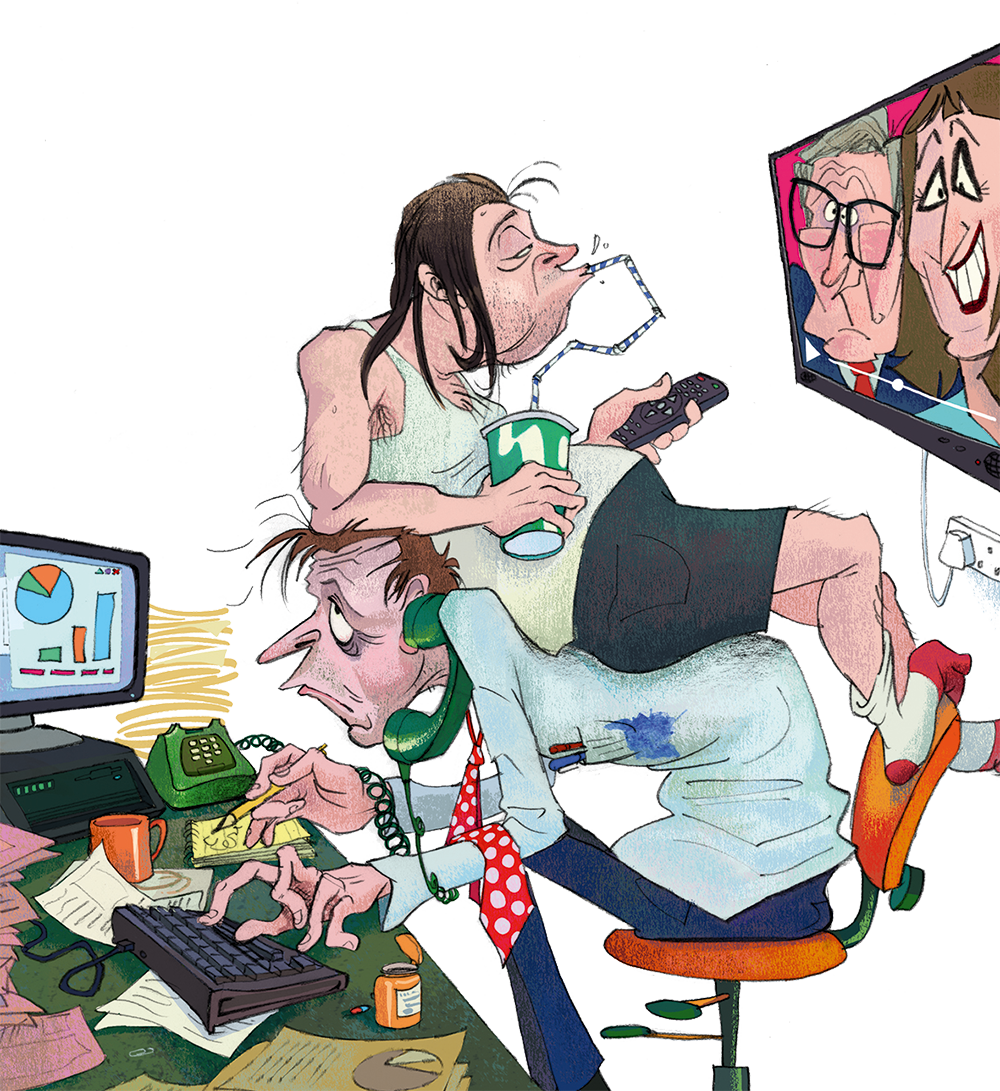

The book is much enhanced by illustrations, more than 100 in colour: we have harengiform images from film (the Marx Brothers as stowaways in kipper barrels, from Monkey Business, 1931), and numerous paintings. Van Gogh’s 1889 canvas of smoked herrings alludes to his dissatisfaction at the police reaction to his ear incident – hareng saur is slang for gendarme. There is a photograph of Laurence Olivier breakfasting aboard the Brighton Belle, having campaigned for Pullman to reinstate kippers on their menu, though apparently he never ordered them. He was snapped celebrating with a plate of scrambled eggs.

Recipes abound, and although I can’t stand the taste myself (too much compulsory bloater paste back in the nursery), Rigby does seem to find this fish lip-smacking, despite its high purine content affecting his gout. We learn about Yiddish Schmaltz herring, the Swedish delicacy Jansson’s Temptation, how to cure kippers on tenterhooks and the beauties of a Danish dish, Sun over Gudhjem. My idea of Purgatory would be a diet of Surströmming, a fermented concoction from the Gulf of Bothnia so sulphurous that birds flying overhead when a can is opened are said to fall insensible to the ground.

Aficionados of curiosity will learn how voles arrived in Orkney aboard Belgian boats, where they were carried as snacks; how the Irish magician Mannan attempted to poison St Patrick with a herring; that the fish fart, and their shoals emit phosphorescence (‘fire in the water’); that superstitious Manx mariners kept a dead wren in their nets; that in some countries Captain Birdseye is known as Captain Igloo; and that there are more than 150 distinct designs of knitted ‘ganseys’ (not jerseys). In Rigby’s hands all this disparate material is as pleasingly brought together as one of those herringbone patterns.

Ending with ‘Zeno’s Paradox’, Rigby observes that an undertaking such as this cannot be truly complete: ‘A herring encyclopaedia is never finished.’ However, it is a prodigious achievement, by turns erudite and great fun. Dr Johnson’s entry for ‘Encyclope’dia’ reads: ‘The circle of sciences; the round of learning.’ Now, that’s more like it.

Comments