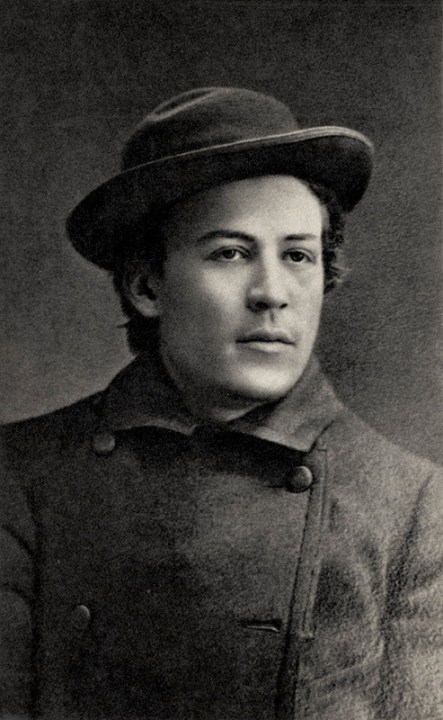

This book collects 58 pieces of fiction that Anton Chekhov published between the ages of 20 and 22. Many appear in English for the first time. In her introduction, Rosamund Bartlett refers to the material with disarming candour as a ‘wholly unremarkable debut’. Is there ever any point in publishing juvenilia?

In his first years as a medical student Anton Pavlovich dashed off these pieces for a few kopecks a line (his father, born a serf, was a bankrupt shopkeeper). Ranging in length from three paragraphs to 76 pages, they appeared under pseudonyms in lowbrow comic magazines that included another Spectator (founded in Moscow in 1881). Unremarkable they may be – but they open a window on provincial Russia in the early 1880s, the tense period before and after revolutionaries assassinated Tsar Alexander II in St Petersburg. The reader will also enjoy identifying the seeds of the master’s mature style; and indeed some of the stories are worth reading in their own right.

Chekhov’s world unfurls in these pages. Character types limber up, preparing to emerge fully formed in the later work – among them Trifon Semyonovich, the owner of 8,000 acres of black earth, who enthusiastically fleeces ‘peasants and neighbours’ in the short story ‘On Account of the Apples’. Orioles whistle in the blackthorn; a tarantass rumbles past, loaded with travelling rugs and hunters’ guns; the whiff of salted fish pervades the spring air and everywhere narrators (often first-person ones) perceive ‘a sense of tedium… in people’s faces and in the whining of the mosquitoes’.

Experimentation with form is less familiar. The volume includes elaborate parody, satire, gothic fiction and sci-fi (in an example of the latter, mischievously attributed to Jules Verne, a fellow from London’s Royal Geographical Society tries to drill a hole in the moon). Chekhov even employs the epistolary form, in part to indulge his fondness for puns. The very first entry consists of a letter written from the village of Eaten Pancakes. The editors have curated this disparate, uneven stuff skilfully. The excellent footnotes explain the abundant wordplay.

As for the translation, the book is the result of a remarkable international collaboration. Eighty-three individuals from nine countries have each translated a piece and then passed it around for team revision. No individual translator’s name follows any one story, but a group credit appears at the beginning. This cooperative approach, a notable success, achieves a consistency often absent from multi-translator anthologies.

Returning to the ‘unremarkable’ aspect of the whole: endings do tend to have a dying fall, as though Chekhov were in a rush to get the thing off his desk. The squibs and comic skits are of the schoolboy variety – though I quite liked the Spectator fake ads, one offering sausage-free worms. ‘The Distorting Mirror (A Christmas Tale)’ was the only piece here that Chekhov included in his first Collected Works, and one can see why. The story has a thematic unity lacking elsewhere in this debut spread.

Chekhov had not found his voice by 1882 – but you can see him searching for it. (One novella foreshadows the theme of his celebrated story ‘The Bet’.) In short, the everyday realism of the later work is on display in this collection, but not its psychological depth. After all, the callow youth had not yet experienced the emotions at the heart of the later great stories and plays. (In Britain he is best known for his stage work; in Russia, for his short stories.) He had not confronted the unfathomable realities of life, nor the ambiguity and nuance that govern human behaviour. We go to the theatre to hear the Trigorins and the Prozorovs express elegiac melancholy – and that is not a young man’s game. On the other hand, the slapstick here humanises the writer whose sense of dramatic economy once caused him to note with approval the effect of placing a pistol on a table in the first act.

What links should we seek between an author’s early and late work anyway? How many of our juvenile preoccupations still concern us in middle age? The man who conjured Uncle Vanya was once a coltish 20-year-old. The trajectory from the inky youth of this book to the titan we know from the plays might be the most Chekhovian theme of all.

Comments