It is hard to write the history of a subculture without upsetting people. Events were either significant or inconsequential depending on who was there, which leads to absurdities. When Jon Savage wrote England’s Dreaming, his history of punk, Jenny Turner berated him in the London Review of Books for being ‘a bit of a Sex Pistols snob’.

Ironically, the most exclusive British subculture of them all seems to have escaped infighting over who or what mattered, possibly because so few people were part of it. The Blitz, Steve Strange and Rusty Egan’s much mythologised early 1980s nightclub, had a brutally selective door policy. Strange let hardly anyone in, which must have made Robert Elms’s task of researching its history, and the so-called New Romantic scene that grew out of it, comparatively straightforward. He dedicates the book to just 115 former ‘Blitz Kids’, himself included. Miraculously, survivors seem to be on speaking terms (Spandau Ballet members’ legal squabbles aside).

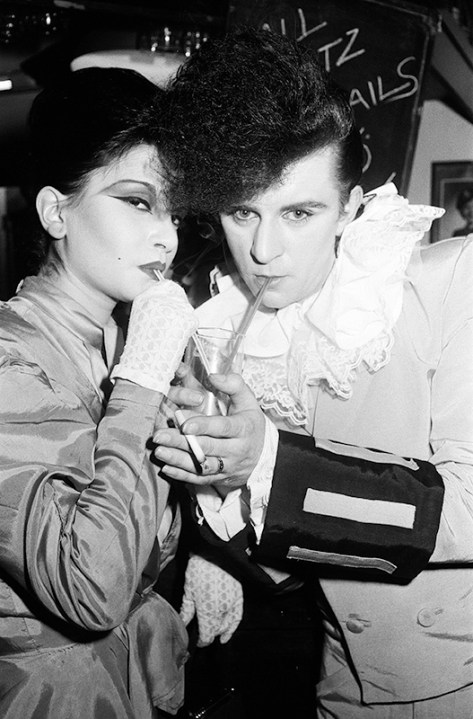

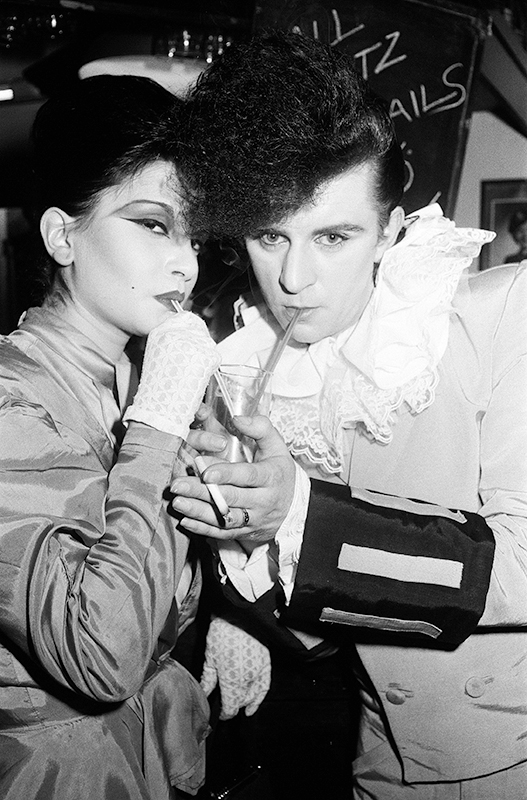

Mick Jagger allegedly fell victim to Steve Strange’s brutal door policy

Elms’s genial, effusive book is about the club and its afterlife, with his recollections underpinning the story of its rise and fall. Other insiders have written about the Blitz before (as has Elms), but this book’s charm lies in its detail, enthusiasm and wistful nostalgia for the certainty of youth. There are no big revelations – the downside, perhaps, of the author being friends with everyone – but there’s much outrageous fun.

Elms is a broadcaster, a working-class Londoner who found fame as a voice of youth in the early 1980s. He was a features writer for the Face and presenter of BBC2’s The Oxford Roadshow (I suspect Ben Elton, a regular on the programme, based the self-consciously shouty presenter of ‘Nozin’ Around’, his spoof yoof-TV show sketch for The Young Ones, on him). Elms mostly eschewed punk in favour of a soul scene which, while studying at the LSE, led him to Strange and Egan’s exotic clubland adventures in Soho. Later, he progressed to Tuesday nights at the Blitz wine bar, Covent Garden, where the only currencies were music and style.

For a brief time, the Blitz was London’s cultural nexus. Even David Bowie turned up (with Karen O’Connor, daughter of Des, in tow) and was allowed in – though Mick Jagger, according to legend, fell victim to that door policy. Dressing up was the point, a way for students and assorted misfits to transcend miserable prospects by dancing to poppy electronica in outlandish costumes, such as those of Weimar-era cabaret performers, 18th-century royalty and futuristic nuns. Elms says this was harder than it looked: ‘Every ensemble had some sort of logic, integrity, intent… you couldn’t let it look like fancy dress.’

The club lasted just 18 months, but it was a concentration of talent. An outsized number of people in Strange and Egan’s tiny orbit became huge international stars: Sade, Boy George, Spandau Ballet, Grayson Perry, Peter Doig and John Galliano. Other Blitz Kids became serious arts professionals: Dinny Hall, Stephen Jones and the Hollywood costumier Michelle Clapton, whose work on The Crown took the Blitz dressing-up box to a 21st-century Netflix audience.

Nostalgia is a serious business, and Elms talks about clubland as he experienced it in quasi-religious terms: ‘Every now and then a nightclub and its young denizens don the vestments of their new creed, learn the songbook and become the focus for the spirit of the age.’ Could they do the same now? Not likely, partly because the Blitz generation swallowed the assets that allowed pop culture to flourish. About a third of UK nightclubs have closed since the pandemic – victims of rent rises and noise complaints among other disasters.

Elms touches on the difficulties now facing young people of his background to shape pop culture. But he is more interested in defending the Blitz against decades-old music press accusations of being ‘the nocturnal wing of the Conservative party’ – a suggestion that still troubles him. He acknowledges traits in common but argues that he and other Blitz Kids were socialists, and, anyway, many were ‘out-and-proud, gender-morphing gay guys’ – hardly natural allies of the architects of Clause 28. Of course the Blitz was Thatcherite, you want to scream, with its individualism, entrepreneurship, aspirations and the promise you could be anyone you wanted to be. Young people are harbingers of the coming age, whether they are aware of it or not.

Still, Elms is great gossipy company. He laughs at the Blitz Kids’ hauteur with affection and he plays up the Partridge-esque: ‘Le Beat Route [a later club] was so cool it was positively scorching.’ His name-dropping and use of the passive tense to anonymise misdemeanours (‘behaviour was disgraceful, liberties were taken’) can grate; but he is self-aware enough to cringe at his early performance poetry (‘Listen to the portrait of the dance of perfection, the Spandau Ballet’) and his wangling of slots for his musician mates on BBC television.

Someone less caught up in the club’s mythology might have written a more clear-eyed critical history of the Blitz, but it would not have been as entertaining. The whole point of scenes is to exclude people.

Comments