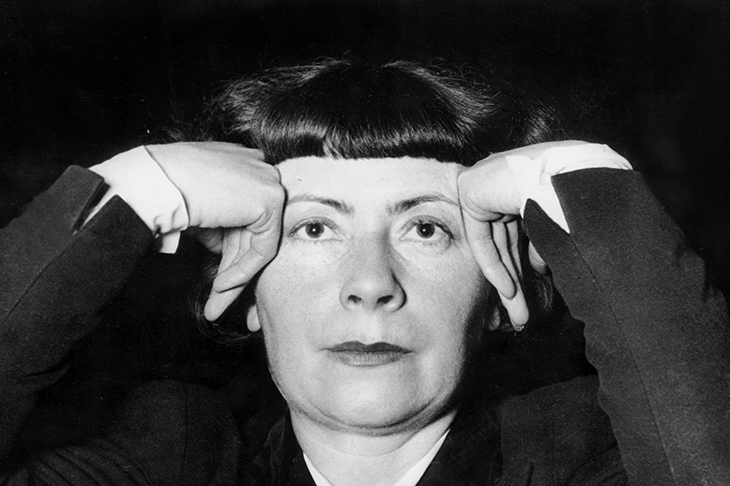

The name ‘Carré’ immediately evokes the shadowy world of espionage. Ironically, however, few people today have heard of the real Carré, also known as ‘Victoire’ and ‘La Chatte’, a female intelligence agent inside Nazi-occupied France whose life had enough plot twists and moral ambiguity to satisfy any spy novelist.

Mathilde Carré (1908-2007) had beena clever but rather neglected child. Desperate to give her life meaning, and inspired by the poems of a patriotic aunt, she had romantically decided ‘at all costs, to die as a martyr for France’. Thirty years later, after a number of false starts, the second world war finally presented her with the chance to live a life of real value. Recruited by Roman Czerniawski, a Polish air force officer stranded in France, she became the crucial French linchpin for his Allied espionage ambitions.

Between 1940-41, before much systematic French resistance had been organised, the two audacious amateur agents built up the hugely valuable Interallié intelligence network. At the end of their first operational year, Carré felt ‘life had grown wings’. The hall light sometimes flickered in time with the dots and dashes of her wireless transmissions, there was a makeshift darkroom in her cupboard, and her medicine packets were full of microfilms. She thrived not only on the knowledge that she was playing a crucial role for her nation, but also on the danger, adrenalin and admiration that this brought. Enter Hugo Bleicher of the Abwehr, in October 1941, and it all went horribly wrong.

Carré had lived with the very real threat of discovery and execution for more than a year. Yet when her arrest was swiftly followed by the stark choice between being shot or turning informer, the terrified agent realised that she was not, after all, ready to die for France, or even for many of her fellow agents. Two months after she had chosen collaboration, she courageously seized an opportunity for redemption. Convincing Bleicher to let her work for him from Britain, she double-crossed him in London and again gave all she had to help the Allied cause. It would be the extraordinary weeks between her arrest in Paris and her arrival in London, however, that would define Carré’s life.

At its heart this is a book about the moral dilemmas involved in living under the perverting conditions of war and occupation, the complexity and cost of collaboration, and the pervasive power of denial. Roland Philipps does a fine job in setting the scene inside France, and building up the tension in this increasingly gripping wartime story, and all that follows. At the height of Carré’s service, the duplicity was so convoluted and the deceptions so manifest that MI6 came to realise that their stories were only credible to others whose trade in lies had expanded their capacity for belief. Eventually they exploited the Abwehr’s gullibility to excellent effect, but it is clear that en route they also exploited Carré.

Like many during the war, Philipps is very taken with his protagonist, whose excellent early service and continued best intentions gives her, he feels, a ‘sizeable credit on her moral balance sheet’. Carré’s abilities and achievements have previously been belittled or ignored, and the trauma of her arrest, abuse and guilt certainly deserves greater consideration. He also rightly notes the hypocrisy of the chummy, overwhelmingly male, British secret services that continued to fête Carré until they abruptly had no more use for her, as well as the failings of the French legal system that later damned her, in part for her sexual liaisons.

The facts remain, however, that while under duress Carré’s actions enabled the arrest, torture and deaths of many in her network, several of whom had been close friends just days earlier. Given this, it seems remarkable that she ever believed she could be returned to service in France. A moral balance sheet may work on paper but serves little purpose in times of war.

Some survivors of her network generously refused to judge Carré. Others felt that all her good work had been ‘washed out’ by her betrayals. Greater consideration of these perspectives and those of the secret services might have brought more balance to this account. There are also questions about Philipps’s judgment of Czerniawski, never viewed through the lens of his Polish identity, and his actions at times almost equated to those of his former protégé.

Carré’s memoirs (originally published in 1959, revised in 1975), which Philipps has mined to good effect, show that she survived her tumultuous war in part because she resolutely continued to believe both in her own worth and that she would finally have revenge. ‘The narrative was as truthful as she could make it,’ Philipps comments, ‘while allowing her to sustain her sense of self.’ Ultimately Victoire is similarly forgiving towards this dynamic but volatile agent, choosing to focus on her ‘human contradictions and vulnerabilities, and her strenuous, sometimes heroic, attempts to overcome those’. In doing so this is a deeply humane book, and humanly flawed.

Comments