In a non-Covid world, next week would be the Tory party conference. Boris Johnson would march on to the stage in Birmingham to receive the adulation of his grassroots supporters. The biggest Tory majority since Margaret Thatcher’s final victory in 1987 would have been celebrated. There would have been cheer after cheer for the new intake of Tory MPs, elected in seats that had been Labour for generations. It would have been a triumphalist conference with much talk of how the Tories had won a two-term victory.

The virus has changed everything. Tory conference is now an online only event with short speeches. Instead of attempting to set the agenda for the rest of the year, Johnson’s own address will be all about ‘delivery’: an attempt to emphasise that the Tories are fulfilling their manifesto commitments despite the pandemic.

The Tories are now behind Labour for the first time since Johnson became leader, albeit only in one poll. Johnson’s own approval ratings are the worst they have been since before last year’s election campaign, according to YouGov.

The grassroots have not fallen out of love with their leader but are less keen on him than they once were; he is now in the bottom third of the ConservativeHome league table of the cabinet, behind Baroness Evans, Brandon Lewis and Alok Sharma. His backbenchers are becoming more rebellious. More than 50 of them signed the Brady amendment, which calls for parliamentary votes before nationwide Covid restrictions are introduced — enough to wipe out the government’s majority if it had come to a vote. In short, it feels very much like mid-term, despite the fact that it is less than a year since the general election.

Johnson’s allies are quick to point out that this government is facing challenges unlike those faced by any other post-war government. In many ways, the fact that the Tories still tend to be ahead in the polls is the remarkable thing. There’s no ignoring the fact that there is no easy political response to the economic and public health problems posed by Covid. Johnson is not naturally suited to the guise he has had to take on, either. A year ago, he would never have imagined that as prime minister he would have to make mass singing and dancing in bars illegal. He is still visibly uncomfortable when he has to deliver bad news.

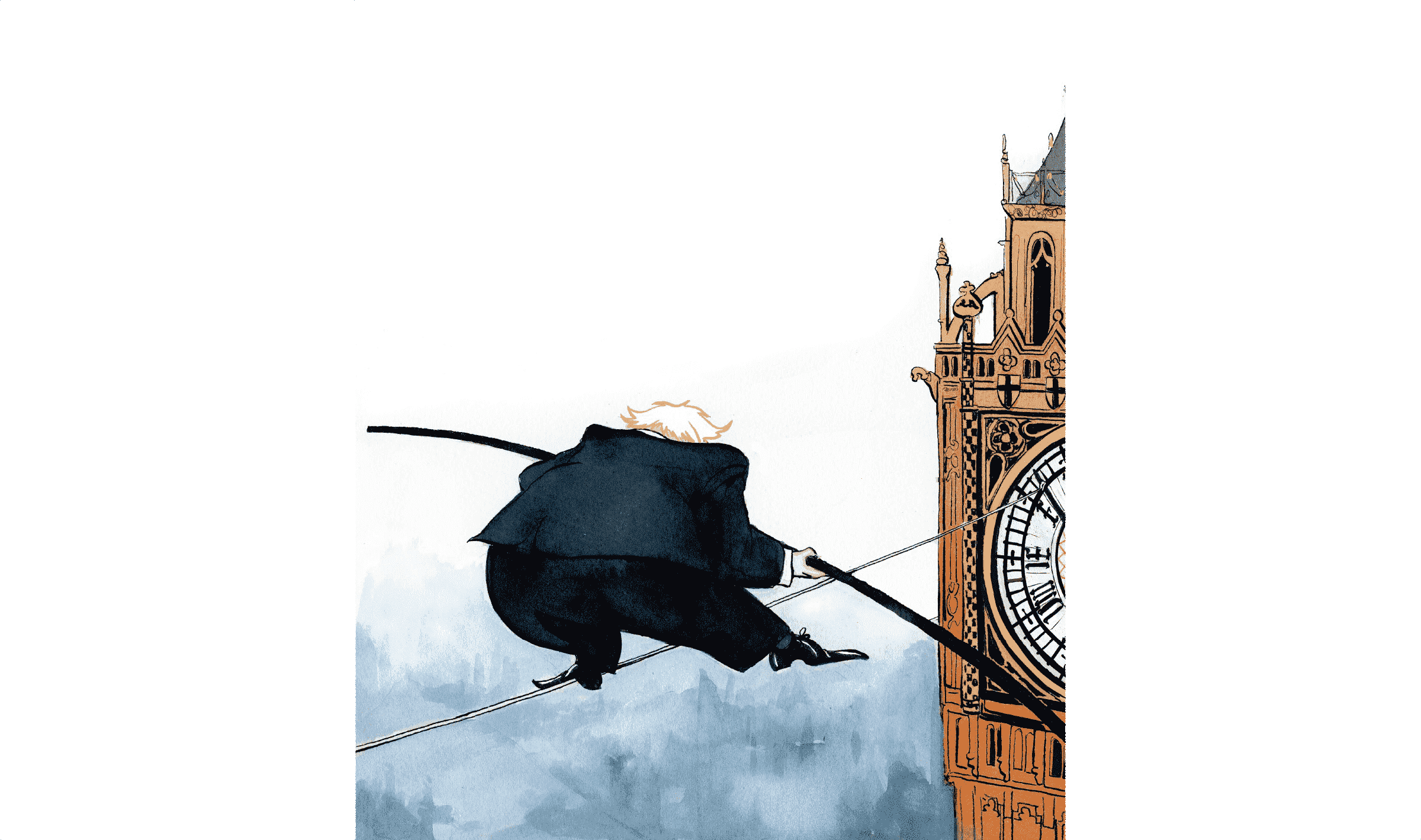

Johnson wanted to be the man who delivered Brexit but his premiership will be forever associated with Covid

This virus has done huge and lasting damage to the government’s reputation for competence. However, perhaps the biggest problem for the UK’s Covid response is how low public compliance is. Research by King’s College London shows that only 18 per cent of those with Covid symptoms isolate for the full two weeks and only 11 per cent of those contacted by Test and Trace do so. If these numbers don’t improve, it is hard to see how the infection rate can be pushed down below one, regardless of what other restrictions are in place.

The government is trying to encourage public compliance by both offering a payment for self-isolation to the low paid and threatening those who don’t follow the rules with ever-stiffer penalties. It doesn’t help matters, though, when the rules have become so complicated that a minister can’t answer questions about what is permitted where in the country. The Prime Minister’s own confusion about restrictions in the north-east of England only made things worse and led to him having to publicly apologise.

Covid has also forced the government to spend its political capital far earlier than it would have liked. This will have an effect on how the government approaches other issues. No. 10 always knew that planning reform would pose party management problems: getting more houses built in the least affordable areas of the country was never going to be popular with Tory activists, but they hoped that the authority that came from their election victory would give them sufficient momentum to push it through. But it is now increasingly clear that the government will at the very least have to tweak the calculation that determines how many houses need to be built where, so as to reduce the pressure on leafy Tory constituencies. (On the housing question, far too many Tories forget that the party is most successful when it is advancing property ownership.)

Johnson’s stated strategy is to suppress the virus until there is a vaccine. There is confidence in both the Department of Health and Downing Street that by March there will either be a vaccine or a breakthrough on rapid mass testing. The government has secured access to six of the leading vaccine candidates so if one does come off, the UK should be in a good position. In these circumstances, Johnson would still have almost four years left before the next general election. He would have a chance to reposition himself as the man who can boost the country’s morale.

But if there is no vaccine and the virus doesn’t become milder, things will become very difficult for the government. The mood in the Tory parliamentary party will turn bleak if restrictions are still needed once winter has passed. Questions will be asked about how viable suppression is as a strategy in these circumstances. More and more Tory MPs would start to argue that there needs to be a different, more Swedish approach.

Prime ministers do not get to choose the crisis that defines them. Johnson may have wanted to be the man who delivered Brexit and levelled up the country, but his premiership will be forever associated with Covid. This autumn and winter will be hard sledding for him. The public will be less forgiving of government mistakes during the second wave than the first, and his MPs will balk more and more at the restrictions on personal and economic freedom. For Johnson, the question now is whether his calculation that the cavalry will arrive in the spring is correct, and whether he has the plan to galvanise the nation for the rebuilding effort that will be needed once this pandemic has passed.

spectator.co.uk/shots - Hear daily political analysis from James Forsyth, Katy Balls, Fraser Nelson and more.

Comments