Coronavirus is deadlier for the old than the young. But for the young, it is economically devastating. A third of working 18- to 24-year-olds have lost work because of the pandemic. Between March and May, the number of those under 24 claiming universal credit doubled to almost half a million, and those who leave school or university this year can expect to earn less a decade from now than they otherwise would have done.

During lockdown the young have, to a remarkable extent, accepted their lives being put on hold to protect their elders. Fairness dictates that steps must now be taken to prevent them from bearing the brunt of the coming recession.

Without help, the young will be hit hard in the next few years. They are more likely to work in hospitality and retail, the sectors that will be last out of this recession. They will also suffer the most from a hiring freeze and are the biggest losers from working from home, missing out on the informal education that office life provides. Those about to enter the workforce face the prospect of higher unemployment than we saw in the 1980s.

The past decade has made the UK complacent about employment. Job growth beat every forecast throughout the 2010s — but productivity remained stubbornly low. In truth, these two things were linked. Many of the new jobs created were in low–productivity sectors, and lockdown and social distancing have forced many companies to work out how they can operate with fewer staff. The consequence will be that the recovery is better on productivity than the 2010s, but weaker on jobs, and that will be more difficult for society to handle. Unemployment has long-term scarring effects, meaning people are less likely to be in work for the rest of their lives.

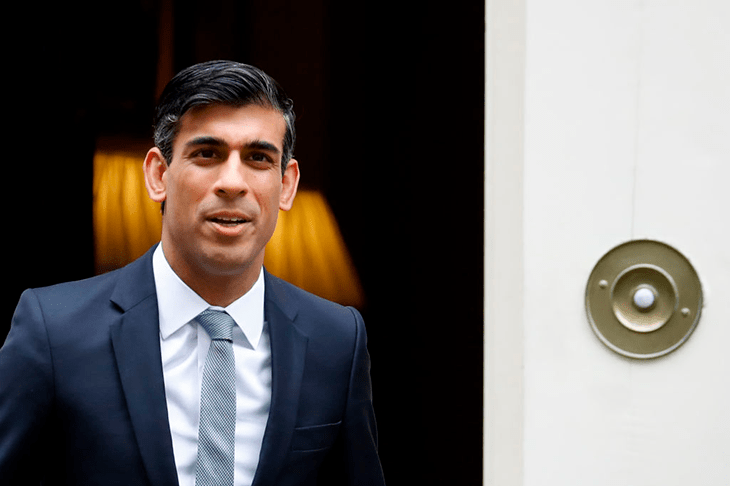

On Wednesday, Rishi Sunak attempted to jerry-rig a solution. The state will, essentially, pay for employers to hire young people for six-month placements. It is another significant intervention in the economy, but must be judged against the alternative. Without these government-backed jobs, youth unemployment would skyrocket. The government’s options are also limited by the furlough scheme. Any attempt to cut or suspend National Insurance for new hires would have the perverse effect of those furloughed being laid off to make way for new employees.

It is revealing that the government is spending £2 billion on these jobs. If it thought the recovery was going to be a reassuring V-shape, it would hardly regard such an intervention as necessary.

But these government-funded jobs can only be a short-term fix. Any medium-term solution is going to require fixing post-16 education. The expansion of higher education has not worked out as intended; the 50 per cent target for pupils going to university has been hit, but too many students are doing courses that don’t represent value for money. Research from the Institute for Fiscal Studies shows that men graduating from 23 universities and women from nine earn less after ten years than the average non–graduate. This is emblematic of a broader problem. As Gavin Williamson, the Education Secretary, pointed out in a speech on Thursday, a third of British graduates are in non-graduate jobs. The government subsidises this failing system: the IFS estimates that only 17 per cent of students will pay back their student loans in full.

Unemployment has scarring effects, meaning people are less likely to be in work for the rest of their lives

Williamson’s response to this problem is to drop the 50 per cent target and focus on further education instead. This autumn, he will publish a white paper on how to set up a German-style system of technical education. Employers will have a direct input into the curriculum, ensuring these qualifications really do set people up for work. In addition, the government will stop funding thousands of low-quality qualifications.

Ministers have been trying to bring this German-style technical education to Britain for many years, without success. There is reason to think this time might be different, however. The government has asked to be judged on its success in ‘levelling up’ Britain, and any attempt to do that which doesn’t fix technical education is doomed to failure.

Perhaps the greatest generational issue in Britain, though, is housing. The average age of a first-time buyer is now 33, rising to 37 in London. This problem has been compounded by quantitative easing, which has pushed up asset prices, benefiting existing home-owners and disadvantaging those trying to get on the ladder.

In the next few weeks, the government will publish planning reforms designed to simplify the system and free up more land for development. It is by far the government’s most significant supply-side reform. One of those involved says ‘this is what the Thatcher government should have done but didn’t’.

The plans would see the UK move to a zonal system of development. In certain land classes, building would be actively encouraged, with a presumption in favour of development. The Housing Secretary, Robert Jenrick, has pushed aesthetic standards, influenced by the work of the late Roger Scruton, which he believes will ensure new homes are more attractive and so garner greater local support. Given this government has already backed away from plans to ease Sunday trading laws in the face of parliamentary opposition, it is easy to wonder if it will do the same here. Tory opposition to planning reform is less than it once was, but there are still many Tories uncomfortable with more building on their patch. The current economic emergency should, though, give this reform sufficient momentum and, crucially, this — unlike the coalition’s effort — is an attempt to revive the housing market through supply-side, not demand-led, reform.

The old vote in higher numbers than the young, and so political parties have tended to prioritise the former. The coalition’s triple lock protected pensioners from the cuts to working–age welfare in the past decade. But it would be an abomination if the state pension increased by a double-digit amount next year at a time when millions of working-age people are unemployed — which it might well do if the triple lock is not reformed.

The test of the government’s extraordinary measures to keep the economy going is not just whether they shorten the length of the recession, but whether they succeed in stopping today’s school-leavers and graduates from being scarred for life by this virus.

Comments