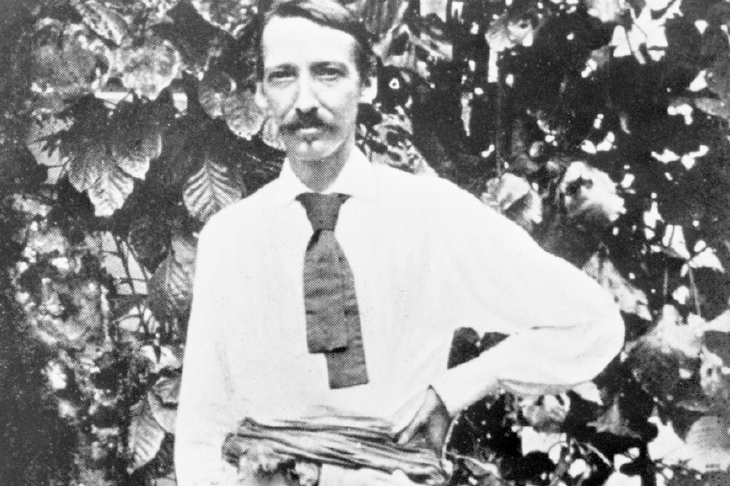

Towards the end of his life, Robert Louis Stevenson travelled widely in the central and southern Pacific Ocean. As well as the region’s exotic reputation, he was drawn by hopes that its benign climate would alleviate his chronic bronchial problems. In 1889 he arrived in Samoa and decided to settle there.

He was a hit with the locals. Unlike so many of his peers, he declined to dismiss them as savages. Certainly, he was scathing about their disregard for property rights, which he labelled communism, and he found some of the women’s dancing obscene. But Joseph Farrell tells us that Stevenson was relaxed about extensive tattoos and scanty attire, and that he was a willing participant in kava drinking (kava is a narcotic plant extract, recently banned in the UK).

Stevenson’s arrival coincided with an imperial scramble for territory in the Pacific. Germany, Britain and the US all wrangled over Samoa, lured by the profits to be made from coffee, cocoa and copra (dried coconut flesh). The interlopers’ greed contrasted with the Samoans’ indifference to material concerns. An abundance of natural resources meant that personal possessions and gainful employment were alien concepts to them.

They were woefully ill-prepared for foreign incursions. There was a Samoan king but his powers were largely nominal, and internecine conflict was rife — a gift for colonial powers primed to divide and rule. Stevenson led a busy life on Samoa. Nevertheless, along with building a house and managing his extended family, he involved himself heavily in the Samoans’ travails. He despatched letters to the Times on their behalf and wrote a lengthy tract about the injustices perpetrated upon them, entitled A Footnote to History: Eight Years of Trouble in Samoa.

Unfortunately, Stevenson’s interventions, like so much else in his life, were as erratic as they were dramatic. He asserted that the Samoans’ overriding need was to be let alone. He argued for the incorporation of Samoa into the British empire. And he proposed himself as the islands’ consul, even as he was being threatened with deportation. None of it made much difference, although he remains a national hero in Samoa to this day.

A Times leader wondered, perhaps understandably, whether Stevenson’s judgment was warped and suggested that he should return to writing romances. Fortunately, his involvement in Samoan politics had not stopped him writing. Far from it: during Stevenson’s stay, Farrell notes, he produced some 700,000 words, right up until his tragically early death in 1894 at the age of 44. In later parts of his book Farrell diligently analyses this mass of fiction, non-fiction and poetry. He acknowledges more than once that its quality is uneven, but is sometimes overly generous in his appraisals.

The finest chapter in A Footnote to History describes a hurricane devastating the colonialists’ warships in the islands’ main harbour. Elsewhere, despite comic leavenings, Stevenson’s denunciations of colonial misconduct make hard going. Farrell tells us, unsurprisingly, that this is the least read of Stevenson’s books. More rewarding is In the South Seas, an enthralling account of his travels in Oceania, cannibalism and all. We are told that a Marquesan islander he encountered was partial to eating hands, though recipes go unrecorded.

The picture is mixed, too, in respect of those novels written during his stay which are set in Scotland. Catriona will always be outshone by Kidnapped, while the unfinished Weir of Hermiston continues to divide critics. In this period Stevenson was trying to move away from romance and adventure, and towards realism and modernism. His efforts had limited success. Even so, of the fiction which draws on his South Seas experiences two novellas stand out. The Beach of Falesá presents white incomers as barbarians, while The Ebb-Tide (co-written with Lloyd Osbourne) goes rather further and is, as Farrell puts it, a ‘strangely haunting’ work. Joseph Conrad read Stevenson’s works assiduously and The Ebb-Tide’s evil magus Attwater appears distinctly Kurtzian.

Recently academia, in its own erratic fashion, has reclaimed Stevenson. As well as finding favour, inevitably, with post-colonialists, the postmodern equation of high and low culture means that the enduring popular fiction from earlier in his career — Treasure Island and Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, as well as Kidnapped, as if you need reminders — has prompted renewed attention. Such studies mostly neglect Stevenson’s mastery of prose. As G.K. Chesterton said of Stevenson’s style, ‘he seemed to pick the right word up on the point of his pen, like a man playing spillikins’.

The other key to Stevenson’s genius is that so much of his writing was fuelled by his lifelong wanderlust. He saw more of the world than most people of his time — of ours too, for that matter. Farrell provides a welcome service by offering us the fascinating story of Stevenson’s last great roll of the dice, his adventure among the Samoans.

Comments