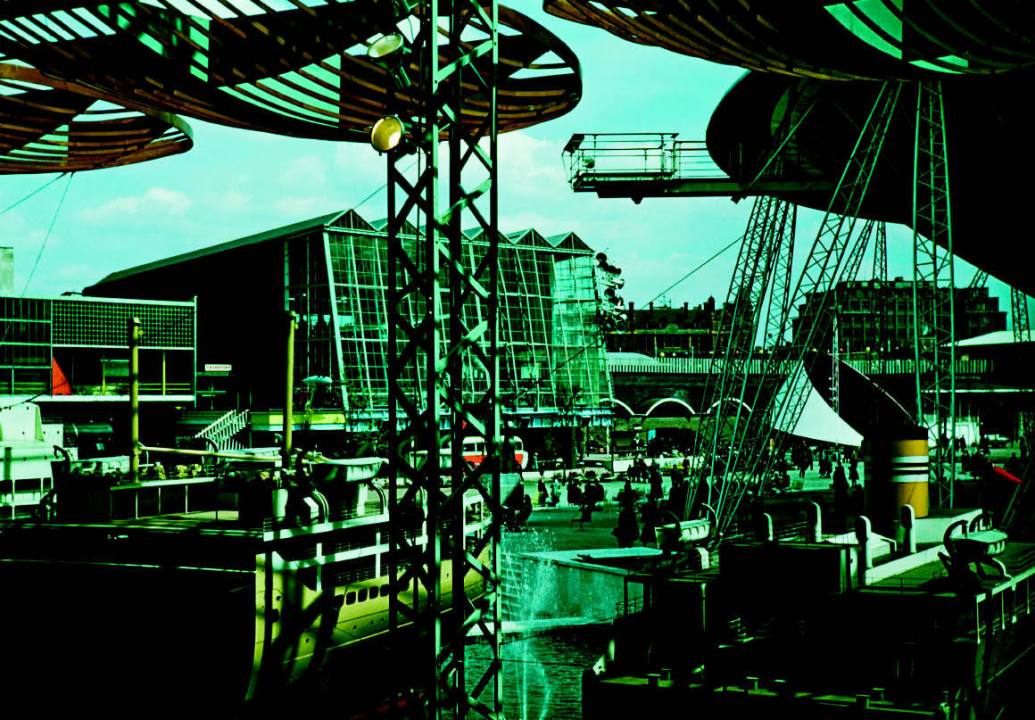

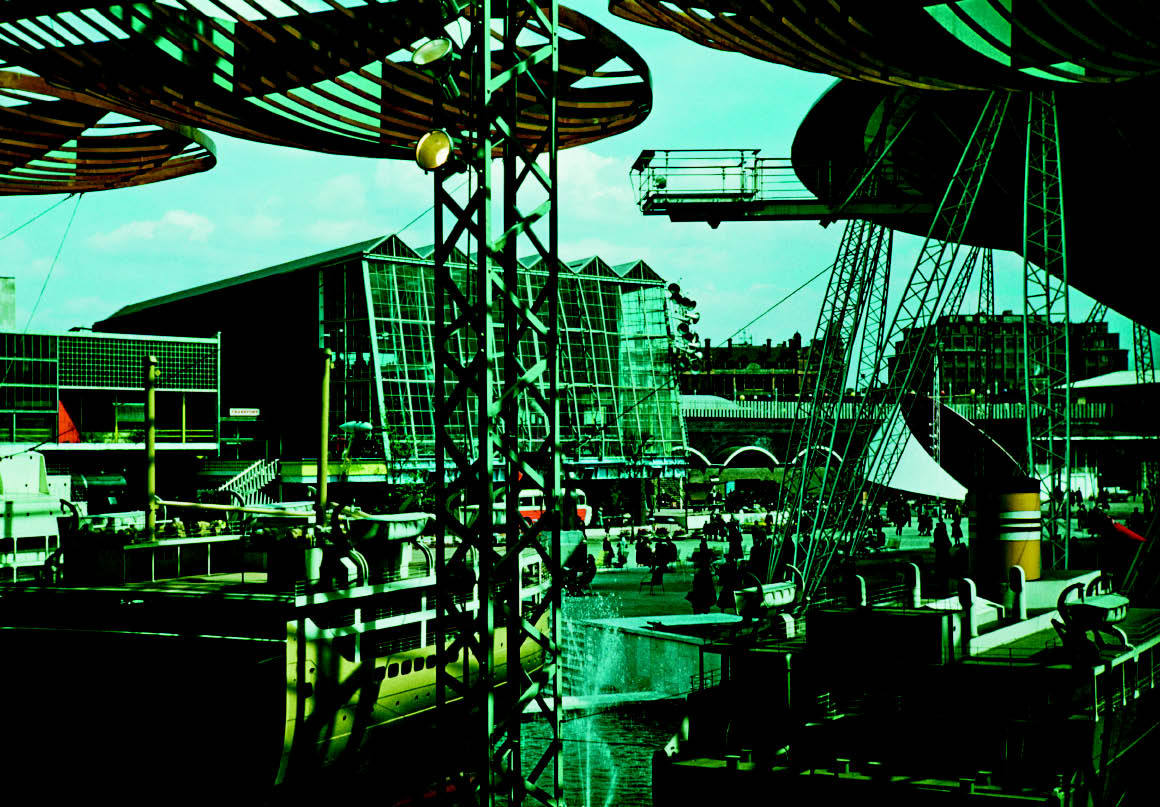

The author of this book and I both visited the 1951 Festival of Britain on London’s South Bank as schoolboys.

The author of this book and I both visited the 1951 Festival of Britain on London’s South Bank as schoolboys. He was 13, I was 11. We were both old enough to remember the war. We were both enduring the post-war austerity. Much was still rationed. Everywhere there were bombsites. From his generally commendable account, I know we both had a similar reaction to the Dome of Discovery, the Skylon and all the other attractions: there was a sense of renewal, lightness, colour, modernity and excess, in contrast to the drabness and penny-pinching we were used to.

In 1976, 25 years after the Festival, Mary Banham and I organised an exhibition at the Victoria & Albert Museum to commemorate it. It was opened by the Queen Mother, who had opened the show in 1951 with King George VI. By an irony, Mary was the wife of the architectural historian Reyner Banham, who had had a part in the Festival but was severely critical of it.

You might imagine that forming an exhibition of things from only 25 years back would be much easier than assembling a show of things from two centuries earlier. But Mary Banham and I found that was not the case. If you want to put together a show of, say, Reynolds paintings or Chelsea porcelain, all you need do is write to galleries and museums with a sort of ‘bring out your dead’ message. Everything is likely to be well catalogued and well restored. But relics of 1951?

Few museums had made any attempt, by 1976, to hoard Festivalia. And it didn’t help that the Festival was seen as a Labour-initiated show, and that the succeeding Conservative government, under Churchill (who had always loathed the Festival) had ripped down its chief monuments, except for the Royal Festival Hall, as soon as they could.

All the same, we did marshal the exhibits for the V&A show. That, like the Festival itself, has gone; but what survives is the catalogue that Mary and I edited. Like the show, it was entitled A Tonic to the Nation — that was the phrase in which the Festival’s masterly director-general, Sir Gerald Barry, summarised what he hoped it would be. What was most valuable in that catalogue — and it has certainly proved of value to Barry Turner, who quotes from it extensively — is the mass of contributions we got, not only from the leading organisers of the Festival (among them, Hugh Casson, John Piper and Osbert Lancaster) but also the ordinary punters.

Not all of the latter were enthusiastic. One of the people Turner quotes from our catalogue is Margaret (Margo) Bean, who happened to be a friend of mine. She had founded an agency called Tomorrow’s News, and this was her caustic verdict on lunch at the Festival’s Regatta Restaurant:

The slatternly waitress with a dirty dishcloth over her arm took our order, and an enormous helping was dumped on our plates. An order for wine caused consternation. ‘Wine!’ she said in horror and went away to confer with the news that nothing was available except British sherry or (I think) someone’s invalid port . . . Afterwards she wrote out the bill and stuck the pencil behind her ear, and we paid at the desk.

But most of the visitors to the South Bank found the experience thrilling.

What has Turner been able to add to what quite a few scholars have now had to say about the Festival? Well, first and foremost, he has had access to Barry’s unpublished Festival diary, letters and notes. Before taking on direction of the Festival, Barry had been editor of the doomed News Chronicle. That trade gave him two advantages. First, he knew all about deadlines. And second, he could write. The many extracts from Barry’s writings that Turner throws in spice his narrative.

His own style is somewhat blokeish. For example, recording that four London double-deckers were enlisted to carry the Festival message to 25 cities in eight countries, he writes: ‘A crew of eight London Transport drivers, led by the splendidly named Frank Forsdick, were English to the core.’ And was it strictly necessary, in recalling how in his home town of Bury St Edmunds ‘a girl of generous appurtenances’ lost her ‘frilly top’ during a Festival entertainment — her cartwheeling ‘delectable beyond the wildest dreams of hormonally challenged teenagers’ — to add that when the adults had left the hall, ‘we in the choice seats were taking our time rearranging our clothing’?

While in carping mode, I must point out the worst flaw of this book: no colour plates! Over and over again, Turner emphasises that the Festival brought colour to drab, bomb-scarred Britain. As one of his epigraphs he quotes Barry: ‘1951 should be a year of fun, fantasy and colour.’ On page three Turner tells us ‘The Festival colours were startling.’ So they were, but there’s not a smidgen of them in this book: one imagines that was a false economy by the publishers rather than any choice of Turner’s.

But Turner understands the Festival in a way that, I suspect, no one who didn’t go to it can. The Labour Government might view the national beano as a demonstration that Britain had recovered from the war (of course, she hadn’t); but as Turner writes:

On one point everyone who paid their five shillings admission (four shillings from mid-afternoon) was agreed: they were there to enjoy themselves.

As he adds, the notion of having fun was distinctly novel in post-war Britain.

His research is admirable. His literary style may not be mandarin; but his diligence in ransacking old newspapers and government edicts is that of a scholar.

A lot of that concept of ‘fun’ which he rightly sees as central to the Festival finds its way into Turner’s text, though in relating that one of the earliest enthusiasts for the show was Sir Alfred Bossom, an architect who had built Art Deco skyscrapers in America and then become a Conservative MP, he misses the chance of a blokeish joke — Churchill’s comment: ‘Bossom? Neither one thing nor the other.’ He also misses the 1951 quip about the Skylon, the Festival’s vertical feature which was politely described as ‘cigar-shaped’: ‘Like the British economy, it has no visible means of support.’

There are many laughs to be had from this volume. One example:

A small boy caught his head under one of the legs of Henry Moore’s Reclining Figure. Pushing and pulling were to no avail until someone applied liberal quantities of soap. According to Barry, the boy was finally liberated by his whole body being lifted into horizontal position and slid out ‘like a missile from the breech of a gun’. His mother reported that her son’s neck had never been so clean.

The Festival was infused with that particular kind of whimsy that lasted through the 1950s but was consumed by the white heat of the technological revolution in Harold Wilson’s 1960s —and by the ‘new brutalism’ (Reyner Banham’s phrase) of 1960s architecture. Years before Laurie Lee won fame with Cider with Rosie, he appointed himself ‘resident jester’ of the Festival. He appealed in the Times for ‘models made of unlikely materials’ and other curiosities. In the ideas flowed: one was for a deflatable rubber bus for going under low bridges. Rowland Emett’s delightful Far Twittering and Oyster Creek Railway was Fifties whimsy in excelsis.

Turner devotes quite a bit of space to what happened to the Festival effects, but he misses the stylish litter-bins. I happen to know that they were mostly bought by Sir Billy Butlin for his holiday camps. In 1959, between school and university, I worked at Butlin’s, Skegness, alongside the comedian Freddie ‘Parrot Face’ Davies. One of my colleagues there wondered where Sir Billy had bagged the bins. ‘They lay about me in my infancy,’ I told him.

As for the lasting influence of the Festival, Turner cites the colour of Terence Conran’s wares; but also, he rightly notes the limitations of the influence. For instance:

The flat-fronted gas and electric fires displayed at the Festival as heat-efficient and a saving on space were admired for their ingenuity but largely rejected by consumers wedded to the bulbous imitation log fires which were better at suggesting warmth than actually delivering it.

Turner makes the inevitable comparison between the 1951 Festival and the Millennium debacle of 2000. Barry refused to have any sponsorship: as soon as you have sponsors, you have those sponsors trying to tell you what to do. (He who pays the piper…) And Barry insisted on an easily accessible site, unlike Greenwich. What a mistake it was in 2000 to have a Dome, which could only seem a déjà vu of ’51. Above all, what the Festival had and the Millennium farrago didn’t was one first-rate person put in charge with, as Turner says, as wide a brief as possible, and with a great deal of autonomy: he was a benevolent dictator. Lord Mandelson, as ‘Dome Secretary’, could have done the job for 2000 (appropriately, as the grandson of Herbert Morison to whom Barry answered), if he hadn’t had his fingers in so many pies; so could Simon Jenkins.

I believe the lesson was learnt. Lord Coe was put in charge of the 2012 Olympics. He has, literally, a track record as a winner. He would never allow his reputation to be sullied by failure; and already we see deadlines being sweetly met.

Comments