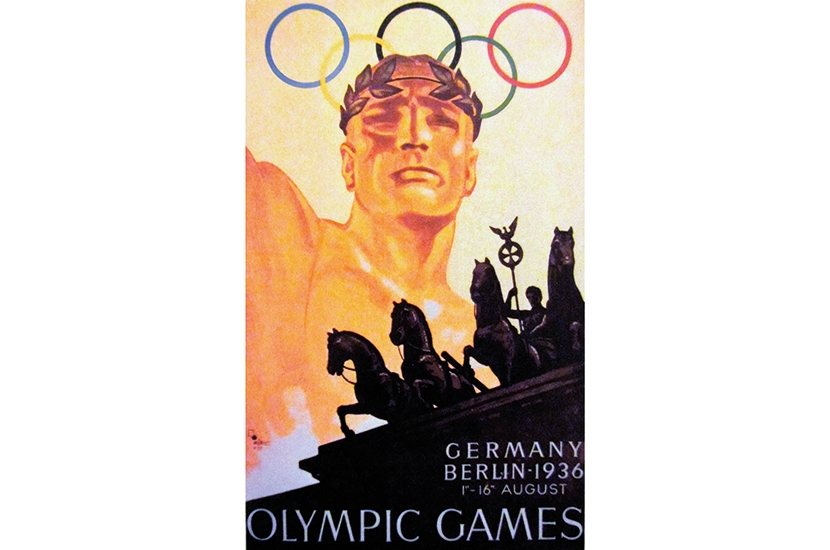

It’s an uncomfortable truth, but the Olympic Games in their modern form were pretty much invented by the Nazis. They came up with the idea of the torch relay, for example, the one that begins in Olympia and ends with the lighting of the cauldron at the opening ceremony. But it wasn’t the events at the 1936 Olympics that were new, so much as the way they were presented and filmed.

Even today, the style of coverage owes much to Leni Riefenstahl, Hitler’s favourite filmmaker and arguably the most gifted and influential female director of the 20th century. Her ground-breaking techniques, as seen in her cinematic masterpiece Olympia, included low camera angles, smash cuts, extreme close-ups and tracking shots in a trench she had arranged to be dug alongside the long-jump pit. She also attached automatic cameras to balloons to get aerial shots for the first time.

Her greatest innovation was the use of waterproof cameras that worked in the swimming pool. They followed divers through the air and, as soon as they hit the water, the cameraman dived down with them, all the while changing aperture and focus. Riefenstahl, who had been a film star before turning to directing, was more interested in artistic expression than sporting competition and this culminated in her hypnotic high-diving montage. So subtle and abstract was Olympia in this section that cinema audiences didn’t realise they were at one point watching a diver emerging from the water, flying backwards through the air and returning to the board.

To say that Riefenstahl was a controversial figure is to understate. By the time she was commissioned to make her film about the Berlin Olympics, she had already made her name as the director of Triumph of the Will, the award-winning film of the 1934 Nuremberg rally. Although she was never a member of the Nazi party — an investigation by the Allies at the end of the war concluded that she was a ‘fellow traveller’ only — her earlier film had nevertheless proved a powerful propaganda tool for Hitler.

Having watched her films and read the various biographies of her while researching my new novel, The Dictator’s Muse, in which she features, I went to visit the Olympic stadium in Berlin. The authorities had considered knocking it down in 1998, but instead decided that the building could be repurposed as a football stadium. The re-inauguration came in 2004.

While the rest of the German capital lay in ruins, this magnificent piece of architecture, built in the style of a sunken amphitheatre, remained intact. In fact, the only part damaged in the war was the bell tower. As you follow the curving, pillared exterior of the stadium, hewn from Franconian limestone that almost glows in the light, you come to the giant bell that later fell to the ground and never rang again. It is rusty now and cracked, but the giant eagle motif on its side is still visible. The authorities welded over part of the small Nazi symbol at its bottom edge, it being illegal in Germany to display a swastika — just as tour guides are banned by law from pointing out things with their arms extended stiffly, in case this could be misconstrued as a Hitler salute.

Goebbels ordered Riefenstahl to edit the black athletes out of her film, but she refused

It’s easily done, as the French Olympic team discovered in 1936. When they paraded around the stadium in their blazers and berets for the opening ceremony, they gave the traditional Olympic salute, with arms raised to the side, but to the commentators it looked like a Nazi salute. To the German crowd too, which greeted the gesture with a roar of approval. The British team came next and did an ‘eyes right’ instead, without raising their arms. This was met with a significant silence.

Continuing around the outside of the stadium you come to a large gap in its west end, the Marathon Gate, and here the hairs on the back of your neck rise as you read the names of some of the 1936 gold medal winners carved in stone. Among them are: ‘100m Lauf Owens U.S.A.’; ‘200m Lauf Owens U.S.A.’; ‘Weitsprung Owens U.S.A.’ That the words are in German make them seem more poignant.

Joseph Goebbels, Germany’s propaganda minister, ordered Riefenstahl to edit the black athletes out of her film, but she refused. In fact, her representation of the great Jesse Owens is entirely positive, and he is repeatedly described by the commentator in the film as ‘the fastest man in the world’. Owens is shown not just winning his four gold medals (the fourth for the 100m relay)but grinning endearingly down the lens of the camera afterwards. If Hitler was depicted as a Wagnerian deity in Triumph of the Will, it is Owens who gets the heroic treatment in Olympia. It’s hard to see how the sections of the film which focus on him so appreciatively could have served the Nazis’ white supremacist cause.

Because more than 250 miles of film was exposed in the making of Olympia, it took Riefenstahl two years to edit it. Then began a series of gala premieres in the capitals of Europe, including Vienna, Paris, Copenhagen, Helsinki and Oslo. At each there were banquets, welcoming speeches from ambassadors and bouquets of flowers. In Graz, hundreds of young girls in Styrian costumes formed a guard of honour from Riefenstahl’s hotel to the cinema. In Stockholm, members of the audience rose spontaneously to their feet and sang ‘Deutschland über Alles’. In Brussels, the Belgian king attended and Riefenstahl curtsied in the manner she had been hastily taught by one of his equerries. And at the Venice Biennale, Olympia was awarded the Mussolini Cup, beating the bookies’ favourite, Walt Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.

The plan was that this would all culminate in a screening in New York’s Radio City, the biggest cinema in the world, followed by a triumphal cross-country American publicity tour. Riefenstahl was due to meet Louis B. Mayer, Charlie Chaplin and Clark Gable, as well as her old friend Marlene Dietrich. But it all went horribly wrong. Just after she arrived in New York in November 1938, news broke of Kristallnacht, in which more than 1,000 synagogues throughout the Reich were burnt and thousands of Jewish businesses vandalised. After Riefenstahl declared to the American press that she didn’t believe these shocking reports, there were protests outside her hotel, led by Dorothy Parker. No studio boss in Hollywood would see her after that, with the exception being, of course, the somewhat right-wing Walt Disney. Having planned to stay in Hollywood and become an American citizen, Riefenstahl was instead obliged to return to Germany.

In her unreliable memoirs The Sieve of Time (1987; 1992 in English), she gave her version of the extraordinary events she lived through in the 1930s. Some of her accounts are what today we would call ‘alternative facts’. While it was true, for example, that she was a libertine who kept what amounted to a harem of handsome actors, cameramen and athletes on call, she describes a #MeToo moment in which an American athlete she was sleeping with during the Berlin Olympics stepped off the medal platform in front of the 100,000-strong crowd, ripped open her blouse and kissed her naked breasts. None of the journalists present reported this, which rather suggests that it didn’t happen.

Yet she was right about the Olympics being sexually charged, as Usain Bolt and the Swedish women’s handball team would later attest. This was one of the reasons I wanted to set my novel, about conflicting loyalties and a doomed love affair, against the Berlin Olympics. It has since become a tradition, indeed, to supply free condoms to athletes in the Olympic village. In Tokyo this year 150,000 will be provided. Promiscuity among Olympic athletes may even have been another thing that the Nazis invented.

Nigel Farndale’s The Dictator’s Muse is out now.

Comments