Like his contemporary and fellow Yorkshireman, Alan Bennett, whom he slightly resembles physically, David Hockney has been loved and admired throughout his lifetime. He painted one of his greatest works, ‘A Grand Procession of Dignitaries in the Semi-Egyptian Style’ in 1961 while still at the Royal College of Art. He has dazzled, surprised and often upset the world of art ever since. Picasso aside, he is the wittiest modern painter, in the sense not just of being funny, but intelligent; a whole history of Western art is both contained and extended by his originality.

For example, it was both funny, and in the 1960s brave, to apply Boucher’s soft pornography to bums as well as bosoms. Andy Warhol made jokes about consumerist society’s dependence on the disseminated image. Hockney’s great joke, a serious one, has been seeing off abstraction. Asked by a puzzled viewer what a random splodge on a large Californian interior signified, he said that it was the world’s smallest Clyfford Still.

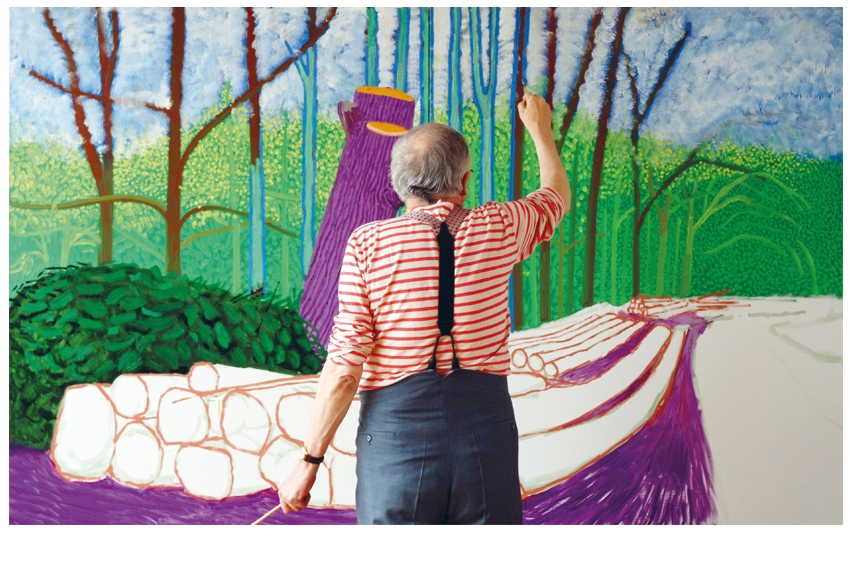

To Hockney, figurative painting and drawing is a constant of civilisation. You cannot interpret the world without it. Indeed, the way you interpret the world has been conditioned by the optical illusions you have grown up with, whether handmade from some imposed fixed perspective, or mechanical, like a still or moving photograph. If you want to live fully you must educate your eyes and learn to look again. Hockney’s vast body of work — he has sketched, drawn, painted, etched, printed, modelled, photographed, filmed, faxed, iPhoned and iPadded illustratively for nearly 60 years — provides the instruction. He is both truthful and entertaining. In the unfair way of life, he happens also to be well-read, musical, eloquent and Britain’s snappiest dresser.

His eloquence has been put to good use by Martin Gayford, whose previous book was an absorbing account of being the subject of a portrait by Lucian Freud. Freud is a wonderful painter, but to me he is a less interesting artist, or maker, than David Hockney; he is not all that interested in composition. Gayford has kept himself in the picture sufficiently to nudge and stimulate Hockney, whose book A Bigger Message effectively is. Gayford provides, therefore, a companion to David Sylvester’s Conversations with Francis Bacon, a key text for modern art. We are treated to many Hockney perceptions. Two favourites: ‘Caravaggio invented Hollywood lighting’ (now I understand why I admire and dislike this painter) and ‘Photographs are surfaces, not space which is more mysterious even than surfaces.’

The book’s title is shared with a large oil painting of 2010. Hockney’s concentration, in this last decade, on the landscape of East Yorkshire, a region virtually unchanged since he took a job there stooking wheat in his teens, led him to look again at the work of Claude. His interest in, and mastery of, new technology suggested he ‘clean’ Claude’s 1636 composition ‘The Sermon on the Mount’ in New York’s Frick Museum. He built up, and stripped down, images of the painting on his computer, thereby altering the painting as it stands, revealing hidden details, transforming the colours.

He was working, as Gayford puts it to him, ‘on a virtual Claude as you might on one of your own paintings’. The virtual Claude turns into an actual Hockney. Dialogue between dead and living master is akin to Picasso’s conversations, in old age, with Velasquez and Delacroix. Technology assures that the subject is revelation, not style: the art, the science, of seeing.

I have not encountered ‘A Bigger Message’ and cannot judge it subjectively.But its place in the Hockney narrative is exciting. Gayford says that having overturned — contestably — the theory of art history with his book on lenses, mirrors and optical projections, Hockney has now moved on to virtual conservation.Pigeon feathers are likely to fly in this field as well.

Hockney says:

I am greedy for an exciting life. I want it to be exciting all the time and I get it, actually… I can find excitement, I admit, in raindrops falling on a puddle and a lot of people wouldn’t.

Hockney describes how in East Yorkshire, in spring, he works 18-hour days. ‘People don’t seem to realise blossom doesn’t last long. If you are dealing with nature, there are deadlines.’

It is fascinating, and also in a way predictable, that an artist whose international fame rests on his discovery, his invention rather, of Los Angeles as an idea for painting (an LA oil sold for eight million dollars recently, and so few left are tradeable, I suspect this may only be the beginning), should in his seventies extend Claude and Constable and Turner within the boundaries of a small and largely ignored patch of rural Britain.

I first visited LA in the mid-1970s, after the major Californian Hockneys had been completed. The city looked like they did, not the other way around. Now, with good companion Gayford in hand, I cannot wait for the Bridlington journey.

David Hockney: A Bigger Picture, the first major exhibition of new landscape works, will run from 21 January – 9 April 2012 at the Royal Academy of Arts, London

Comments