Mussolini’s brutal sex-addiction makes for dispiriting reading, but provides material for a fine psychological study, says David Gilmour

Bunga bunga may be a recent fashion, but adultery for Italian prime ministers has a long history. The first of such statesmen, Count Cavour, had affairs with married women because he was too nervous of being cuckolded to risk having a wife of his own. One of his successors, Francesco Crispi, suffered such amatory turbulence that the police were often called to break up screeching rows between his wives and his mistresses; in old age he was accused by the press of trigamy because he had fathered children by two women in consecutive years while being married to a third.

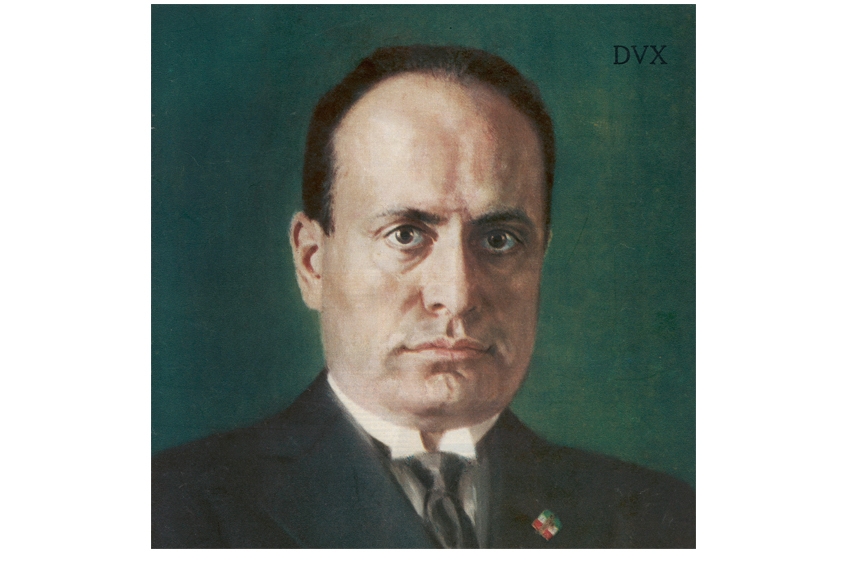

Silvio Berlusconi clearly devoted more time to dalliance than Cavour or Crispi, who were after all serious politicians. Yet even he may have been overshadowed in this sphere by the fascist prime minister Benito Mussolini. In this engrossing book Roberto Olla guesses that the Duce had about 400 ‘relationships’, some of which endured a decade or more. Many of them, however, lasted barely half an hour, including the time taken to undress and tidy up afterwards. No moments were wasted on a chat or a cup of tea.

Mussolini served his sexual apprenticeship chiefly in brothels, and later admitted that he regarded all women as prostitutes: sex with them, he said, was ‘like screwing a whore’, they existed simply for his ‘carnal pleasure’. Strutting about, rolling his eyes, scowling and jutting out his chin, he was proud of his violent behaviour. Women preferred ‘men to be brutal’, he asserted, ‘like cavalry soldiers’. He wanted them to tremble at his ‘love-making’ (sic), because it was like a ‘cyclone, uprooting everything in its path’. Returning to equestrian imagery, he told one lover he wished he could have ‘entered [her] on a horse’. In the aftermath of his ruttings he often felt disgusted, not of course at his own behaviour but at the women who had submitted to it. ‘I am an animal,’ he liked to brag, convinced that no human being more resembled a lion; ‘afterwards I felt nothing but disgust. I wanted to beat her up, throw her on the floor.’

Rachele Mussolini’s first experience of her future husband was in a school classroom when, deputising for his mother as the form teacher, he whacked the young pupil’s hand with a ruler. Violence remained intrinsic to the subsequent ‘courtship’. As he later recalled, he got Rachele ‘down on an armchair and, in my usual way, roughly took her virginity.’ His engagement was even rougher: confronting both Rachele and her mother, he brandished a revolver and threatened to shoot them both if the girl rejected him. For a couple of decades he saw Rachele just often enough to have children but not enough for him to feel too disgusted. They lived in different cities until 1929, when she and their children moved to Rome to share the Villa Torlonia. Even there he contrived to see little of his family.

In his early years in government, Mussolini lived in Rome in a hotel and then an apartment where, he later boasted, he had ‘14 women on the go and would see three or four of them every evening, one after the other’. Later his routine became more regimented. He would entertain different ladies each afternoon in his office in the Palazzo Venezia, often taking them ‘roughly’, without lying down or even removing his boots. In tenderer moments he allowed the ‘regulars’ to spread themselves on a carpet underneath his desk, while ‘newcomers’ were led to a stone seat with a mattressy cushion by the window. A few privileged ones were permitted to visit him in summer at a private beach where the Duce liked to idle, sunbathing, zooming about in his motor boat and playing bowls with his chauffeur.

Numerous children were born from his liaisons, but he only recognised one of them — and later regretted this solitary act of weakness. No weakness graced his discarded mistresses, whom he used to mock to their successors. One of them, he declared, was now ‘an old witch’, while another was ‘faded’ and ‘flabby’, generous descriptions compared to a third who had become ‘an old whore, a filthy bitch’ now resembling ‘an old slack cow — you could fit several . . . well, you get my meaning.’

Of his sophisticated Jewish mistress, Margherita Sarfatti, to whom he owed much of his early success, he related how her ‘terrible smell’ had rendered even him, Don Juan himself, temporarily impotent. After a relationship that had lasted many years, he could not be bothered to dump her in person and assigned the task to his valet.

Reading about this ineffable creature almost makes one warm to Berlusconi, who at least likes women, caresses them, gives them presents, sings love songs and treats them as people. Mussolini neither liked nor respected women: they should have babies, do the housework, obey their husbands and occasionally submit to a good thrashing. Yet he did not particularly like men either, once admitting that he had not had a male friend in his entire life. Women often fell for Mussolini though they rarely fell in love with him; and some of them, as Olla demonstrates, were important to him in ways beyond sex, often in ways that he refused to acknowledge. Sarfatti was a powerful influence on his ideas, but others were important too, especially Clara Petacci, the last mistress-in-chief, who was killed with him on Lake Como in April 1945 and whose recently published diaries provide Olla with much of his material. Mussolini preferred to trust women rather than men.

It is a pity that author and publisher have tried to sensationalise this book. The cover claims that ‘no intimate detail is spared’ (not true) and that the text is ‘enriched by first-hand documents’ (also not true — they have already been published); and Olla states in his opening sentence that ‘this book is about sex’, before warning in a titillating way that readers should understand this before turning the pages. This is meretricious stuff, and unnecessary, because the work, though not as original as it claims, is a fine psychological study.

The biographer rightly puts sex at the centre of the myth of Mussolini; it was indeed at the centre of his life, though unaccompanied by any semblance of love or romance. Fascism, as its anthem ‘Giovinezza’ proclaimed, exalted youth, and with it both virility and violence. Mussolini’s carefully nurtured masculine image helped him to power, just as power enabled him to have as varied a sex life as he wanted.

That potency then encouraged him to delusions of invincibility, to squander both his credit and Italy’s resources on wars he regarded as virility contests. Towards the end of his life he recognised the truth of his sexual decline and accepted aphrodisiacs prescribed by Dr Petacci, the father of his mistress. Tragically for himself and for Italy, he failed to recognise commensurate truths about the poor quality of his leadership and the inefficiency of his regime.

Comments