Ten years ago today, Islamist terrorists massacred 130 people in a coordinated attack across Paris. It was the heaviest loss of life on French soil since the second world war, and those who perished – as well as the 350 who were wounded – will be remembered today in a series of commemorations. Emmanuel Macron will visit the six sites where the terrorists struck, among them the Stade de France and the Bataclan concert hall, and the president will also inaugurate a memorial garden at Place Saint-Gervais, opposite Paris City Hall.

According to the Élysée Palace, the day will be an opportunity for the nation ‘to honour the memory of those who lost their lives…and reaffirm its ongoing commitment to the fight against terrorism’. Since 2015 the DGSI – France’s MI5 – have thwarted 80 Islamist terror plots but 50 attacks have been launched, 19 of which were fatal, nearly one every six months.

The organiser of the day of remembrance is Thierry Reboul, who oversaw the opening ceremony of last year’s Paris Olympics. He says the commemorations will honour ‘the dead and the living, but also our culture, which was attacked that evening, with a moment of collective unity’.

‘Islamo-Gauchisme’ is now de rigueur among the far-left

To bring France together is an admirable aim, but is it achievable? It has been tried before without success. A week after Islamists murdered the staff of Charlie Hebdo in January 2015, schools in France held a minute’s silence in their memory. In over 200 establishments pupils refused to respect the silence. A similar request for silence was made in 2023, in memory of the teacher Dominique Bernard, who was fatally stabbed in the schoolyard by an Islamist. Some pupils in 350 schools chose not to comply.

These acts of rebellion should surprise no-one. A comprehensive study published in 2021 reported that 65 per cent of Muslims pupils in French schools consider Islamic law superior to Republican law.

The figure wouldn’t have surprised François Hollande, who was president of the Republic in 2015. He described the assault on Paris as ‘an act of war’. The following year a book was published, A President should not say that, in which Hollande confided in two journalists. ‘It’s true that there is a problem with Islam,’ he told them. ‘No one doubts that…we can’t continue to have migrants arriving unchecked, especially in the context of the attacks.’

If vast numbers of migrants from Africa continue to arrive unchecked, Hollande warned, ‘how can we avoid partition? Because that’s what’s happening: partition.’

Since Hollande made those observations, unchecked immigration into France has reached record levels, prompting other significant politicians to warn of partition. ‘Today we live side by side,’ said Interior Minister Gerard Collomb in his resignation speech of November 2018, ‘but tomorrow I fear we will live face to face’.

In the two years since Hamas attacked Israel, anti-Semitism in France has reached ‘alarming’ levels and a recent poll disclosed that 31 per cent of 18- to 24-year-olds believed it acceptable to assault Jews because of the Gaza conflict.

Synagogues have been burnt, Jews beaten up in the street and last week four pro-Palestinian protestors stormed a Paris concert hall, letting off flares and shouting threats as the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra performed.

On Monday, a parcel bomb exploded in the Montlucon agency of the German financial services company, Allianz, injuring one employee. Days earlier, the Toulouse branch of the company had its windows smashed. An extreme-left group claimed responsibility for the Toulouse attack, justifying it on the grounds that Allianz insures an Israeli drone manufacturer.

The intimidation of the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra drew scant comment from far-left MPs. A minority, such as Thomas Portes of La France insoumise (LFI), celebrated the intrusion, declaring: ‘We must multiply these actions! We are on the right side.’

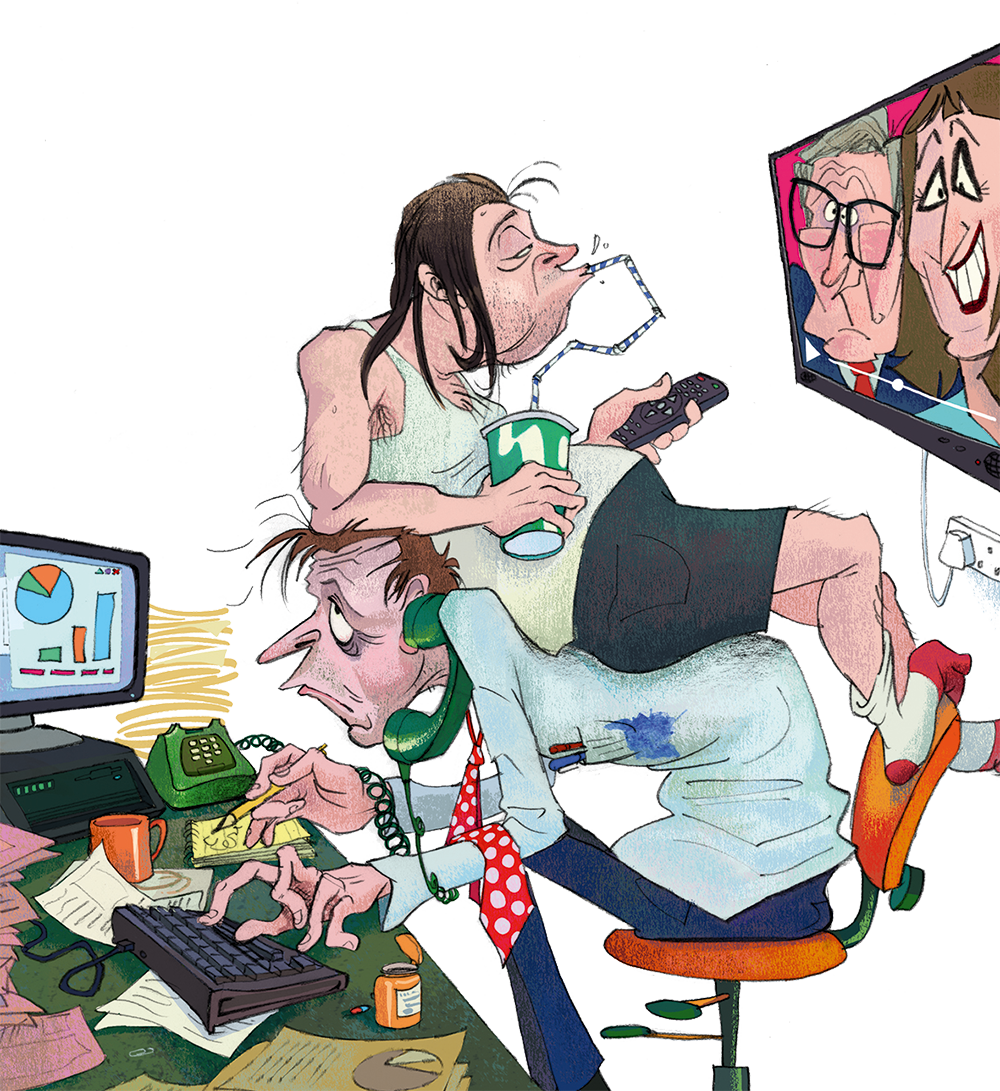

‘Islamo-Gauchisme’ is now de rigueur among the far-left. Another LFI MP, Nathalie Oziol, stated earlier this year that it was wrong to blame the beheading of schoolteacher Samuel Paty in 2020 on ‘a Muslim fanatic’. Rather, it was an issue of ‘resources, hierarchy, and how the government views national education.’

In an op-ed in Tuesday’s Le Figaro, the academic and expert on Islamism, Gilles Kepel, expressed his fear that the Islamists were exploiting the left’s useful idiocy to win the ‘cultural battle’. Certainly they are winning the hearts and minds of a growing number of young French Muslims.

The Islamist attack last week on the holiday island of Oleron overshadowed the revelation that three women aged 18, 19 and 21 were charged with plotting to bomb a concert venue ‘in homage to bin Laden’. This is not an isolated case. Nearly 70 per cent of people arrested on suspicion of terrorism are under 21 and over half are motivated by a desire to avenge Gaza.

There will be grief, poignancy and dignity across France today as millions pause to remember that horrific evening in Paris ten years ago. But there will also be delusion. Not among the people, three-quarters of whom told a recent poll that they expect more Islamist attacks in the future, but among the political elite.

France is not united; it is divided. To deny this reality dishonours the dead and endangers the living.

Comments