I encountered Frederick Ashton at a dinner party shortly before he died in 1988. Frail and anxious, he clutched my arm and demanded to know which of his creations I thought would survive him. I duly reeled off some titles, but felt that any opinion I expressed would have disappointed him. In public, he professed to care not a fig for posterity, but he evidently did, and his will set out thoughtful arrangements parcelling ownership of his works out to various trusted colleagues, with the bulk passing to his nephew, the Royal Ballet’s administrative director Anthony Russell-Roberts.

How exhilarating to be reminded of Ashton’s remarkable range, and of choreography so inventive

This may have seemed like a sound investment, but it turned out badly. Ballet is the art form that depends most crucially on transmission from the muscle memory of one dancer to another. Notation and film can’t convey nuance or detail, and personal experience of the choreography is vital. Ashton’s legatees were soon crossing swords: there was a sense that productions were being licensed without quality being monitored or staged according to individual whim rather than authentic spirit. As the direct heirs died out, some of their inheritors have proved to be problematic custodians, and there is particular sensitivity surrounding the stipulations of retired ballerina Wendy Ellis Somes, into whose hands – as widow of Ashton’s legatee Michael Somes – the Koh-i-Noor of Ashton’s 1946 masterpiece Symphonic Variations has passed.

Russell-Roberts attempted to steer through the consequent wrangles over what was being danced in Ashton’s name, but without any legal lever, his efforts to bring everyone together informally came to nothing. To stop the rot and the arguments, the Ashton Foundation was established as a charitable trust in 2011.

Based in the Royal Opera House and managed by two expert administrators, Christopher Nourse and Jeanetta Laurence (Russell-Roberts sadly died in January), it has accrued authority, and over the next four years it will sponsor and oversee a worldwide festival of Ashton’s work, with particular emphasis placed on preserving the intricate footwork and upper-body flexibility that are such essential features of his style.

The Foundation aims to spread the word globally and to conserve ballets in danger of being lost or forgotten, but also to ensure that every performance is rigorously rehearsed and deeply understood. ‘Young dancers find Ashton terribly hard – he’s so precise about what he wants and you can’t mess about with it,’ Laurence says. ‘We have to persuade them of the value of getting everything right.’ Although some legatees continue to insist on operating independently, the Foundation is gradually centralising control over Ashton’s corpus and training an elite of approved coaches, as well as holding public masterclasses through which great ‘bloodline’ Ashtonians such as Anthony Dowell can pass on their front-line wisdom.

The Royal Ballet may have been Ashton’s home, but it is relatively unadventurous about exploring his achievements. It has fallen to a small company based in west Florida to be his living museum and research centre. Led by Iain Webb and his wife Margaret Barbieri, two former Royal Ballet dancers, and keenly supported by the Foundation, Sarasota Ballet puts Ashton at the heart of its activities, exhuming and reanimating an astonishing number of his lesser-known works. This summer, the company made its first visit to London to display the fruits of its efforts. It was warmly welcomed.

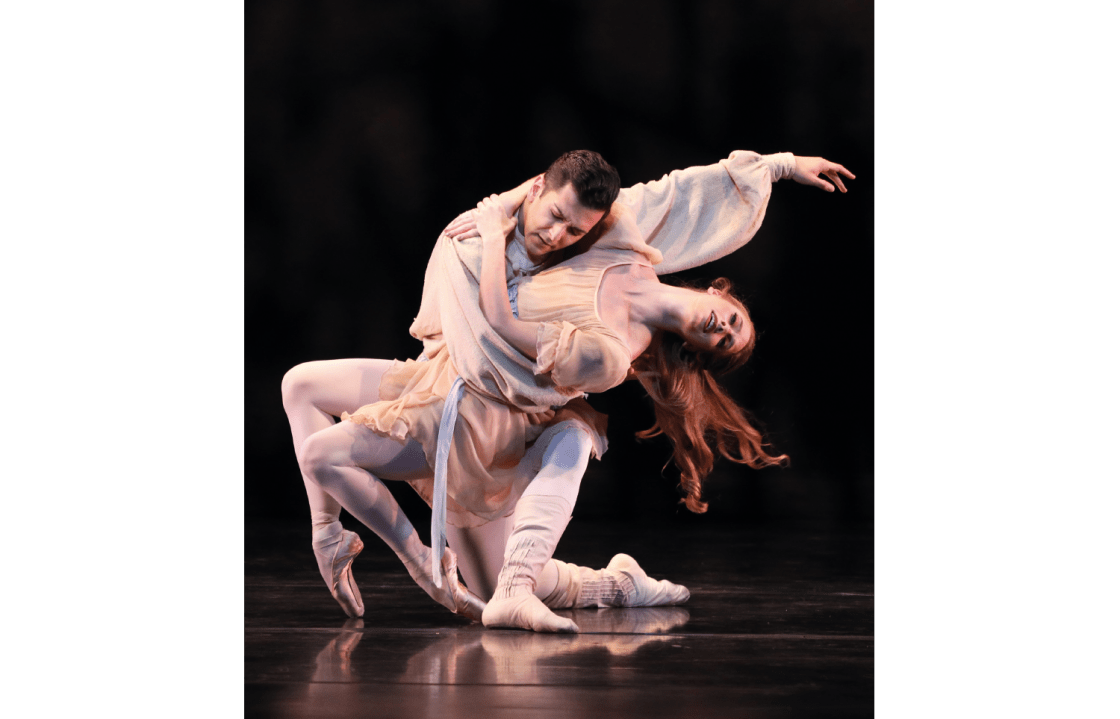

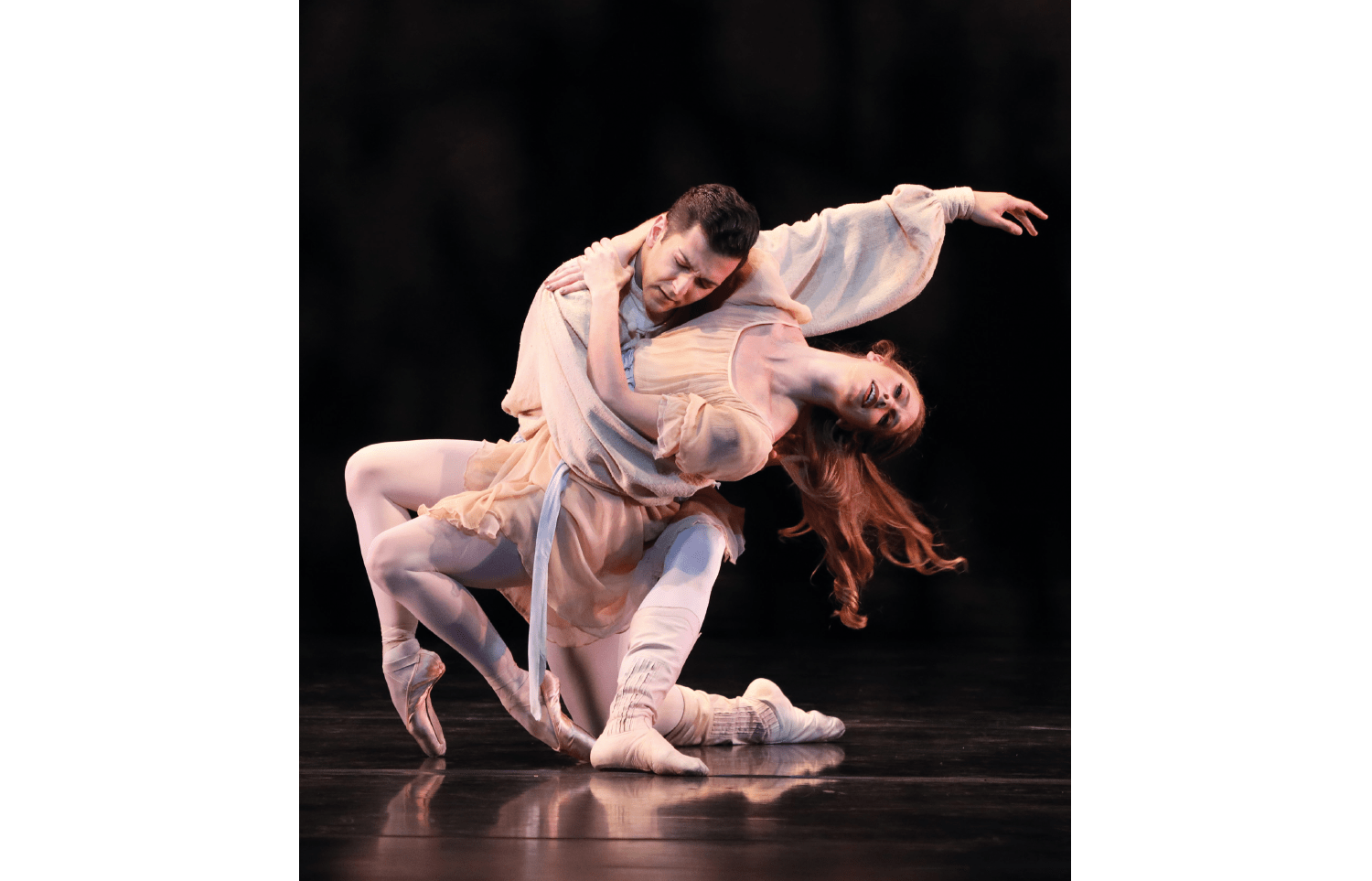

The roster lacks star virtuosos or glamour queens, and it was mildly disappointing that performances were confined to the small, noisy stage of the Linbury Theatre and accompanied by tinny recorded music. But the collective verve of the company’s lovable dancing more than compensated – everyone knew what they should be doing, even if they couldn’t render all Ashton’s subtlest intentions. Highlights of the week included Valses nobles et sentimentales, a charming ballroom caprice with a transcendently beautiful climax; the seraphically aerial central section of Sinfonietta; Dante Sonata (see above), an impassioned parable of spiritual struggle created during the life-or-death tensions of 1940; and the Wodehousian wit of Façade, a delicious satire of 1920s silliness. How exhilarating to be reminded of Ashton’s remarkable range, and of choreography so supremely musical and inventive. More on this subject in a forthcoming column.

Comments