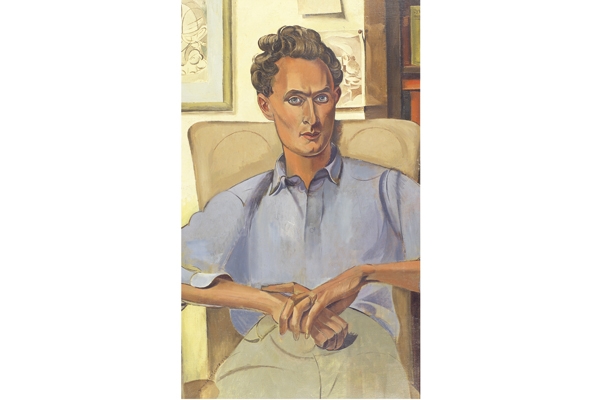

In real life, Stephen Spender was gentle and very tall, with wide-open pale blue eyes and a persistent air of slight hesitancy, as if he expected to be violently contradicted at any moment. He had one of the nicest voices I’ve ever heard, a voice which might have been made for poetry: impossible to imagine it raised in anger. In conversation Spender would bow his head, blink slowly and say ‘yes’ a lot, even if he wasn’t in accord with what was being said; this gave his interlocutor the agreeable (and strangely rare) sensation of being truly listened to. He spoke with openness and sincerity; he could also be conspiratorial and prone to giggles, although he wasn’t really a funny man. He was a generous host. He had a boyish smile. You couldn’t not like him.

I say ‘in real life’, but perhaps I mean in person. For where is a writer’s real life? Is it on the page, on the podium or in private? Such questions are always to the fore, with Spender. Was his true self the poet, the husband, the friend, the editor or the lover? The current volume provides only partial answers. Odd, because this edition of his journals covers more than 50 years. It was whittled down from almost a million words to a still substantial 816 pages. In the decades covered, Spender was this country’s most public intellectual. He taught at universities in America and London, edited Encounter and travelled. He went to Soviet Russia (where he met up with Guy Burgess) and wrote China Diary, about a journey with David Hockney. He published prose, criticism and poetry, became president of PEN and campaigned for good causes. He interested himself in international affairs, music, painting and literature. He was knighted.

There is some pathos in the fact that Spender ‘always considered himself foremost a lyric poet’, as editor Laura Feigel asserts. His verse is not now in fashion — I’d challenge any poet under the age of about 50 to be able to quote more than one line from him — but that may change. He was himself aware that he was better known for his formative and enduring friendships with W.H. Auden and Christopher Isherwood than for his poetry. This he rued.

Yet he seems to have devoted more words to his time with and evolving feelings for these men than to his poetic output in its entirety.

He appears to have been fond of Isherwood, if occasionally exasperated, but about Auden his feelings are less straightforward. In Kentucky in 1979, he suddenly asks himself:

Did I really like Wystan? […] To be totally honest now, I should ask whether Auden was not a bit envious of me because I had a large penis […] If you appealed to Auden for sympathy or help he would be attentive, kind even generous, but like a benevolent doctor or psychoanalyst, whose task it was to provide a diagnosis and prescribe treatment, not of a friend who empathised.

Friends were very important to Spender and he had a great many of them. He was not a writer who craved seclusion. In these pages we encounter Isaiah Berlin, Stuart Hampshire, Igor Stravinsky, Alfred Brendel, Iris Murdoch, Edith Sitwell, Harold Pinter, Henry Moore, Mary McCarthy, Susan Sontag, Lucian Freud, Francis Bacon and countless others. Spender was an unabashed highbrow. He considered it ‘damnable’ that ‘the journalistic spirit always dominates over the spirit of art’, a trend his journals resist. In 1953, he accompanied T.S. Eliot on a lecture trip to America: ‘Tom was nice and rather interesting.’ Sylvia Plath, in 1960, was ‘a very pretty, intelligent girl from Boston’. Dinner with Vivien Leigh was ‘very nice’. Antonia Fraser was ‘really very nice, modest’. Charlie Chaplin ‘is always amusing’. Of course I am biased, but it seems to me that my father Cyril Connolly is the most brilliant and touching and flawed and funny — the most human — of Spender’s friends. He animates the pages on which he appears, a sort of Falstaff to Spender’s John of Gaunt. Cyril loved Stephen, made him the godfather to his first child, me.

The older Spender, perhaps with an eye to posterity, gives more vivid descriptions. Germaine Greer ‘radiates coarse vitality and has the look of a great overgrown girl who has won all the prizes and never quite got round to tidying herself up’. Jacqueline Onassis has ‘a mouth like the opening in a pillar box’ and ‘talks in a way that suggests she is marvelling at everything’.

Spender was a complicated man. Being an intellectual mattered to him tremendously, but he was also a bit of a plodder. He was poetic but worldly, affectionate but not always kind. He had a certain vanity and he nursed grievance. Everything in his countenance suggested guilelessness, yet he had his secrets.

There is bound to be interest in the inclusion in this volume of passages concerning Spender’s lifelong homosexual feelings, including a love affair with an American man some 50 years his junior. An unexplained gap of six years in the journals begs the question as to what other entanglements may have occurred over this time. Spender understandably tried to protect his wife Natasha from this side of his life. Natasha Spender (who survived her husband for some years) was highly intelligent and fiercely protective of her husband’s reputation: that he continued to desire men in no way lessened his sympathy and love for her. Indeed, he often says so in these pages: ‘I have been far the luckiest in my personal life, made up by Natasha, Matthew, Lizzie [his children] — by all of these.’

Comments