Very useful in modern conversation, Oscar Wilde. Not for the quotable quips — everyone knows those already. His real value comes when you’re trying to guess someone’s sexuality. ‘He can’t be gay,’ someone will say of whoever is under the microscope, ‘he’s married with two kids.’ You hit them with the reply: ‘So was Oscar Wilde.’

It’s hardly surprising that so many people are unaware of Mrs W’s existence, or that those who do tend to forget about her, given her husband’s status as poster boy for the Two Fingers to Convention party. You’d be forgiven for thinking that Oscar was a Victorian Alan Carr, standing in the middle of Piccadilly belting out ‘Sing If You’re Glad To Be Gay’. The truth, of course, is that he sued for libel to hide his homosexuality. To the extent that we do consider the question of his wife, we probably imagine a dowdy old boiler (in modern terms a ‘beard’), dutifully providing a couple of sons but otherwise keeping well out of the way. The truth was far more complicated. It always is in the best stories, and this is a very good story, very well told.

Constance Lloyd was a pretty, dynamic, much sought-after young woman when Oscar Wilde, not then as famous as he would become, first fell in love with her. Rebelling against a bully of a mother, she had grown into a proto-feminist. No bras were burnt, but the Rational Dress Society, of which Constance was a leading member, demanded that women shouldn’t be expected to don underwear weighing any more than seven pounds. She ate at women-only restaurants, helped get the first female councillors elected, and, aiding the brothers as well as the sisters, supported striking dockers. But it was her interest in the Aestheticism Movement, with its ‘art for art’s sake’ motto, that led her to choose Oscar from her many admirers.

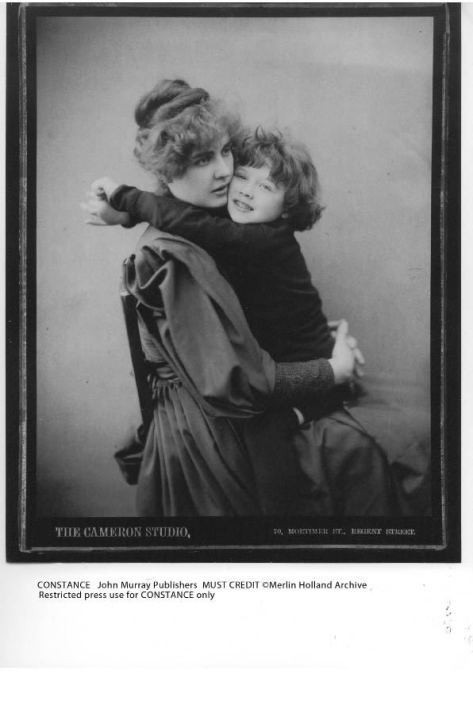

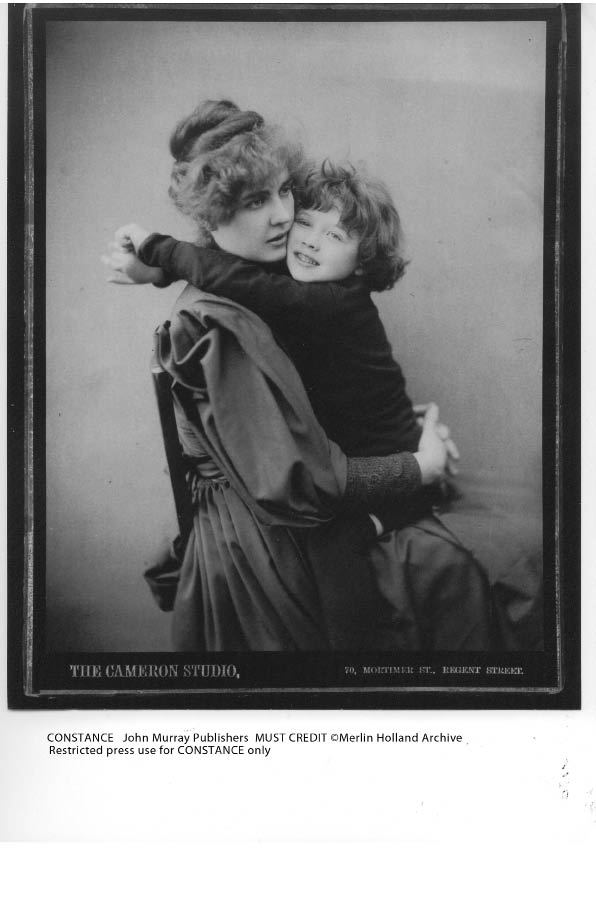

And he really did admire her, with a genuine physical passion. ‘My soul and body seem no longer mine,’ he wrote, ‘but mingled in some sweet ecstasy with yours.’ The early days of their marriage had niggles —he sometimes called her ‘Mrs Cantankeray’ — but no more than would be expected from two people with such strong personalities. They both doted on their son Cyril, and if his younger brother Vyvyan was less favoured it didn’t mean the family unit was any less real, any less important to Oscar. One day he discovered that the boys’ toy milk cart had openable churns. ‘He immediately went downstairs,’ recalled Vyvyan, ‘and came back with a jug of milk with which he proceeded to fill the churns. We then all tore round the nursery table, slopping milk all over the place, until the arrival of our nurse put an end to that game.’

Helping to bring the story to life, and set it in its context, are the details with which Franny Moyle depicts Victorian London. We see the ‘Liver Brigade’, the early morning horse-riders exercising to stay fit. London is ‘literally newly aglow’, as electric light reaches the Embankment. We learn that Gustav Jaeger started as a health campaigner rather than a fashion designer (very keen on wool next to the skin), and that Robert Cunninghame Graham was the first MP to swear in the Commons (‘damn’). Plus there are walk-on parts for people with names that Oscar would never have dared invent for his plays: Charles de Lacy Lacy (Constance’s doctor), as well as a circus act called Rubin Raffin and his Porcine Wonder. Don’t worry, it really was a pig.

Another surprising revelation is that at one point Oscar became obsessed with playing golf. ‘I am becoming a golf-widow’, Constance wrote to a friend. The least of her worries, you might think. Her husband’s companion on the fairways, as well as elsewhere, was Lord Alfred Douglas. It’s his malign presence through the second half of the book that prevents either Oscar or Constance being seen as totally at fault in the breakdown of their marriage. The preening, scheming, selfish little Bosie inhabits the role of villain quite well enough on his own. True, no one made Oscar go to bed with him, but neither did the playwright ever stop caring about his wife. Even after his fall from grace he yearns to treat her as well as possible, attempting (with mixed success) to kick his addiction to the male lover he came to resent.

The end of the tale is as sad for Constance as for her husband. Sadder, in fact — ill-health claims her even before it claims him. But while she has strength she works as hard as possible for her sons, building a new life on the Continent to protect them from the scandal at home. Oscar lay in the gutter and looked at the stars. There weren’t many stars bigger than his wife.

Comments